The backlash against the University of Manchester students who recently overwrote a mural of Kipling’s If, once voted the UK’s favourite poem, with the civil rights activist Maya Angelou’s Still I Rise was predictably fierce. “Liberal fascism” and “outrageous cultural vandalism” were some of the more pointed attacks on this latest incarnation of the drive to “decolonise the university”.

While critics slammed the June episode at Manchester’s students’ union as troublemaking by excessively politically correct students, academia has a fine history of responding to the changing society around it, reconfiguring both admissions and curricula in light of evolving concerns about equality.

This year, for instance, marks the 150th anniversary of the first exams sat by female undergraduates at the University of London, introduced after much opposition. And universities in the post-war period were transformed by opening themselves up to more female and working-class students and staff – in the face of critics who insisted that more would mean worse.

But the voices calling for the decolonisation of universities – and, in particular, their curricula – seem to have unsettled opponents at a deeper level than these previous upheavals did. From calls for an adequate consideration of the legacies of brutal colonialist-turned-University of Oxford benefactor Cecil Rhodes to requests to broaden the reading list of the University of Cambridge’s English literature degree, there has been a systematic pushback by those who purport to be concerned about a decline in standards but who, in reality, seem mostly to be worried about their loss of privilege.

Similar concerns are expressed in the US – although Yale University did respond positively to a petition last year calling on it to “decolonise” its English department by diversifying its curriculum.

Canons and canonical understandings have never been impermeable or immune to change. This is perhaps more easily accepted in the sciences, where it would be absurd to suggest that we should continue to utilise theoretical frameworks or concepts just because they had previously been the standard way of understanding things. The difference with the humanities and social sciences is that in these disciplines the processes of canon formation should be understood more explicitly as being the outcome of collective cultural processes, which take place in the context of particular social and political claims.

For example, when scholars of British history naturalise its violent imperial past, overlooking atrocities or cold-calculated violence meted out everywhere from Kenya to Kilkenny, Rhodesia to Rajasthan, it becomes plausible to understand that history as one of munificence, and to celebrate figures such as Rhodes, or Bristol slave trade magnate Edward Colston. Those who were subject to the violence of the imperial state, however, can less easily airbrush those aspects from their understandings.

Decolonisation processes in the mid-20th century, together with the movement of darker British citizens to the former imperial metropole, have increasingly required conversations between proponents of both positions. However, calls for the partial representation of history to be addressed and for there to be a proper accounting of its violence have more usually been met with outright hostility than engagement with the actual arguments being made.

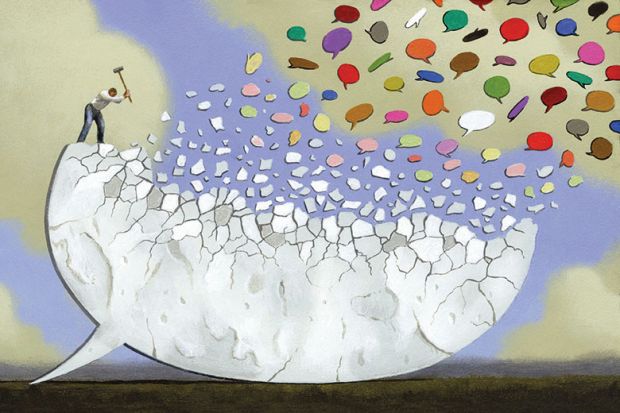

But those whose scholarly positions are based upon the justification of historical governance by domination and exclusion cannot expect their assumed mantle of objectivity and universalism to go unchallenged. As the US education reformer John Dewey argued, universities are vital repositories of the common learning of communities. As those communities change, our understandings are also transformed. No one is necessarily cast out of a canon by those seeking to include others, but a deeper acquaintance with those others often leads to a rebalancing, such that some who were previously taught cede their space to different voices. Who now reads the political theorist Herbert Spencer, asked sociologist Talcott Parsons in the 1930s; the question posed in the 1980s, in turn, was: “Who now reads Parsons?” Processes of canon formation and re-formation were ever thus.

The furore around efforts to decolonise the university should, however, give us pause for thought. Does the concern relate to the proposed changes to the canon or to the changing communities that make up universities? Are opponents unaware of the earlier struggles and analogous arguments made in relation to women, working-class people, sexual minorities and others? Would they endorse the arguments in favour of excluding these groups, whether as students, academics, or subjects within curricula? And if not, why not?

At a time when right-wing forces across Europe are contesting the rights of sexual and religious minorities and mobilising against the teaching of gender studies, universities must reinforce their public function to provide a space for critical engagement. To decolonise the university is to contribute to its ability to perform that role by further democratising it as an institution. To fail to do so is to ensure that certain sections of society continue to have their views ignored as we approach what could be a tipping point in history.

Gurminder K. Bhambra is professor of postcolonial and decolonial studies at the University of Sussex. Her latest book, Decolonising the University, co-edited with Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu, is published by Pluto Press.

后记

Print standfirst: Only by decolonising the university can we fully democratise it

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?