Carrie Tirado Bramen, professor of English (and director of the Gender Institute), University at Buffalo (SUNY), New York

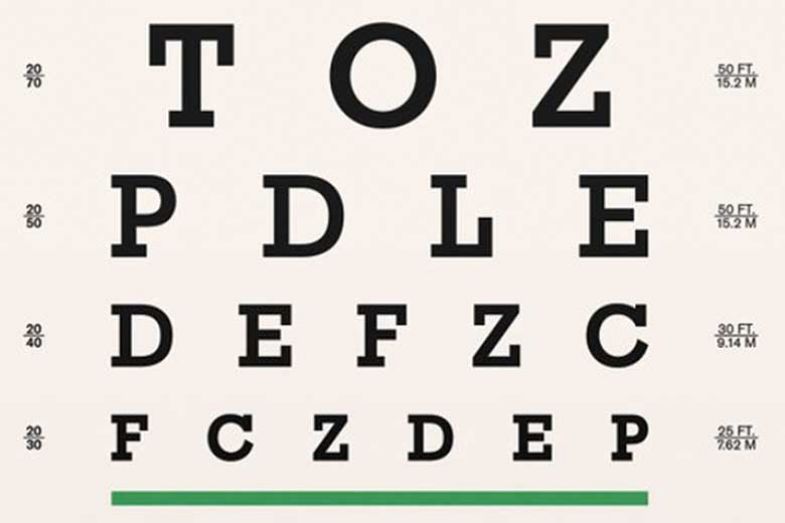

This fall, I discovered the “Object Lessons” series by Bloomsbury, which consists of short books about the hidden lives of everyday objects. I have especially enjoyed William Germano’s Eye Chart. Created by the Dutch ophthalmologist Herman Snellen in 1862, the eye chart has become a standard tool for visual testing; but it has also evolved into an iconic image in popular culture from silk-screened T-shirts to conceptual art. Germano’s style is conversational yet also deeply informative. He manages to turn font design and typography into a fascinating history about the diagnosis of vision. I am looking forward to reading another history, namely Hannah Catherine Davies’ Transatlantic Speculations: Globalization and the Panics of 1873 (Columbia University Press). She examines the crises of the 1870s through three financial centres: New York, Berlin and Vienna. The crises raised urgent questions about how to read financial signs and interpret fluctuations. Given the recent volatility in global markets, Davies’ history of speculation appears to be well timed.

Jim Butcher, reader in geography, Canterbury Christ Church University

Brexit has dominated the year. It has raised questions about the kind of democracy we have, and the one we want. Paul Cartledge’s Democracy: A Life (Oxford University Press) is a fascinating read, looking at the origins of the democratic ideal in ancient Greece and (albeit a lot more briefly) how it has fared historically. Concerns over freedom of speech on campus continue to surface, both here and in North America. I am looking forward to reading Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (Allen Lane). Both authors are well-known advocates for freedom of expression on campus in the US. I hope the book sheds light on the nature of threats to free speech on both sides of the Atlantic.

Catherine Butler, senior lecturer in English literature at Cardiff University

Catherine Fisher’s The Clockwork Crow (Firefly) is perfect winter reading. A poet and novelist of the Welsh Marches, among other liminal realms, Fisher has long been among our most original writers for children, but her new book resounds with gothic echoes: an orphaned girl walking the chilly corridors of a Victorian mansion; button-lipped servants; a strangely absent child. The territory seems familiar, but Fisher’s sidelong eye for magic and pocket worlds make this child’s Christmas in Wales eerily unexpected. Also fit for a dark season, though not due to appear until May 2019, is Robert Macfarlane’s Underland: A Deep Time Journey (Hamish Hamilton). There is no more poetic guide to the Earth’s unimagined corners than Macfarlane: mountains, islands, ways ancient and modern – all open their secrets at the tap of his staff. Now, as such heroic spirits inevitably must, he makes his katabasis. I’m going too.

Sarah Cox, media relations officer (and postgraduate student in history), Goldsmiths, University of London

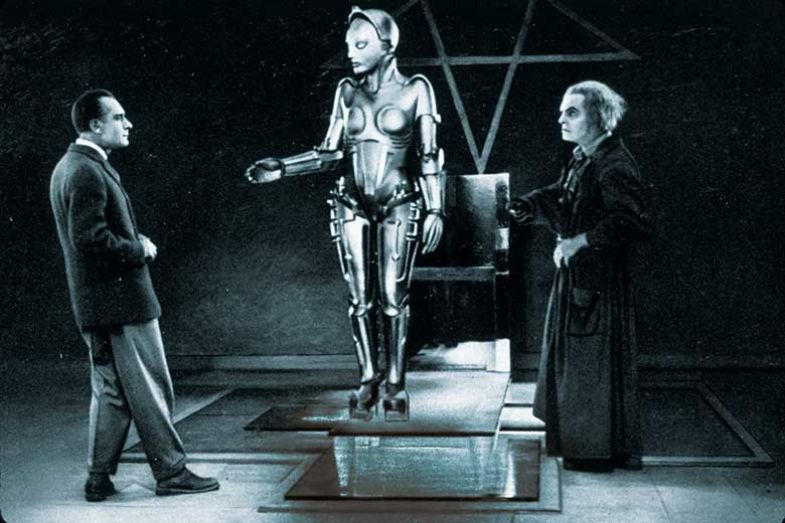

Seeing my name listed in the index of Kate Devlin’s Turned On: Science, Sex and Robots (Bloomsbury Sigma) alongside words I definitely wouldn’t say in front of my mother was a highlight of 2018. Covering everything from ancient Greek myths to new technology and ethical debates in the field of “robosexuality”, Devlin’s book is eye-opening and engaging, with laugh-out-loud footnotes and touching personal anecdotes throughout. I particularly enjoyed her chapter on 2016’s Love and Sex With Robots conference at Goldsmiths – or the “Christmas sexbot festival at top London university” (as a certain tabloid newspaper put it). You’re unlikely to find a conference fringe event with a name to beat “Sex Tech Hack II: The Second Coming” any time soon. I’m really looking forward to Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, out in March 2019 (Doubleday). She’s set out to bust myths that have prevented the real stories of these women from being told, and give them back the dignity they deserve.

Robert Gildea, professor of modern history, University of Oxford

There has been a good deal written seeking to explain Brexit, but my favourite was Philip Murphy’s The Empire’s New Clothes: The Myth of the Commonwealth (Hurst). The director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies elegantly dissects the fantasy of Leavers that having lost its political relevance this institution could turbo-charge Empire 2.0. I am looking forward to reading Mary Frances Berry’s History Teaches Us to Resist: How Progressive Movements Have Succeeded in Challenging Times (Beacon Press). A historian and former chair of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, she should have much of urgency to say about how, when governments and politicians let us down and populism is on the rise, it is up to progressive activism to challenge and redeem the situation.

Barbara Graziosi, professor of Classics, Princeton University

This summer, in the midst of moving to the US, I ended up reading a lot of Aleksandar Hemon: his novels are full of displaced, traumatised, grandiloquent Bosnians, whom I took on trust as my guides to America. On reflection, they may not be entirely reliable on everything – though they are surely right to warn that blasts of air conditioning can give you “lethal brain inflammation” (The Lazarus Project, Penguin). As the autumn set in, having run out of Hemon (I hope he writes lots more, and soon), I started preparing my lectures on myth. I found Oliver Taplin’s translation of Aeschylus’ Oresteia clear and convincing (a little clearer than the original, perhaps…); the introduction and accompanying essays, prepared with Joshua Billings, excellent (Norton Critical Editions). Next on my list: Nancy Worman’s Virginia Woolf’s Greek Tragedy (Bloomsbury).

Aniko Horvath, research associate, Centre for Global Higher Education, UCL

The Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and his “illiberal democracy” are frequently in the news. Kristof Szombati’s book, The Revolt of the Provinces: Anti-Gypsyism and Right-Wing Politics in Hungary (Berghahn) explores the complex processes that have made racism central to mainstream Hungarian politics and turned Hungary into the most right-wing country in the EU. Closer to home, but not unrelated, Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire (Biteback), by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson, is the must-read book about Brexit. It helps us understand how we have been fooled into having a public debate about Brexit that fails to expose the direct economic benefits for those who shout most loudly about the glories of free-trade agreements and “taking back control”. This book links the growth of inequality to the politics and ideology of those underwriting the financing of the Brexit plan.

Ann Hughes, professor of early modern history, emerita, Keele University

The book I’ve most enjoyed recently is David Como’s Radical Parliamentarians and the English Civil War (Oxford University Press). His extraordinary research reveals crucial radical networks, ultimately committed to religious liberty and popular sovereignty. Above all, he demonstrates the centrality of a brave and lively press to radical parliamentarianism, and how crucial radical militancy was to Parliament’s eventual victory. And he offers some grounds for optimism about democratic engagement in our own time. I am really looking forward to a book about the first historian of my home town, Susan E. Whyman’s The Useful Knowledge of William Hutton: Culture and Industry in Eighteenth-Century Birmingham (Oxford University Press), which promises to use the story of “the rapid rise of a self-taught workman” to stress that such “rough diamonds” offer new insights into the nature of the Industrial Revolution.

Rivka Isaacson, senior lecturer in chemical biology, King’s College London

My neighbour, editor Gillian Stern, was possessed by one of her 2018 projects, Putney by Sofka Zinovieff (Bloomsbury). Infected with her enthusiasm, I pre-ordered the book and, while I was desperately awaiting its publication, a copy magically appeared through my letterbox – so I inhaled it. You’d think with this build-up it would have necessarily disappointed but, although it began as an incredibly uncomfortable read, it was a frantic page-turner full of intrigue, humanity and food for thought. Gillian held a book club with the author and friends/family of all ages who’d read it and the intergenerational variations in response led to amazing discussions/looks of disbelief. The book I’m planning to read is Free Woman: Life, Liberation and Doris Lessing by Lara Feigel (Bloomsbury), an erudite memoir starring Lessing and authentic motherhood. From what I have seen of Feigel, we seem to share a lot of literary loves.

David S. Katz, Abraham Horodisch chair for the history of books, Tel Aviv University

To define Slavoj Žižek as a philosopher would be to give a truncated impression of a prolific writer and speaker whose skill is to connect the dots even if that means bending the lines around inconvenient obstacles. I have been reading his The Courage of Hopelessness: Chronicles of a Year of Acting Dangerously (Penguin), a quirky and creative commentary on contemporary culture and politics. Perhaps Žižek should have been a late-night radio man, his accented voice sparkling in the darkness, with unexpected insights enlivened by linguistic misfirings. I plan now to read Michael G. Hanchard’s The Spectre of Race: How Discrimination Haunts Western Democracy (Princeton University Press), in which he widens the lens both chronologically (beginning with ancient Greece) and thematically (seeing racism as a subset of discrimination). Hanchard promises to get to the bottom of a paradox of modern democracies, in which the ideology of equality goes head to head with politically dominant groups that have always tried to exclude others.

Laura Kehoe, postdoctoral researcher with the Nature Conservancy

This year, the book that brought me the most joy was The Songs of Trees: Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors by David George Haskell (Viking). Reminiscent of E. O. Wilson, Haskell is a rare mix of biologist and poet. His first book, The Forest Unseen, is one of my favourites, and he doesn’t disappoint with his next offering – which isn’t just about trees, but about the very essence of a life well lived through the connections that we make. He weaves science with artistic prose in such a uniquely beautiful way, I know I’ll be reading both of his books again and again. I’m looking forward to reading George Monbiot’s new book, Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics for an Age of Crisis (Verso), which asks: “What does the good life – and the good society – look like in the 21st century?” – tough questions to answer, but certainly worth a try.

Robert Montgomerie, professor of biology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

It’s the summer of 1971 and we are leadfooting it back to Fort Churchill, Manitoba to catch the tail end of the dinner hour at the military base. After a long day’s fieldwork studying lemmings on the tundra, we are famished. But just as we pull in, the CBC Evening News ends and Cedric Smith, an Ontario folksinger, begins reading a new epic poem/novella, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid by Michael Ondaatje (Anansi), a young author unknown to us. For half an hour, we sat transfixed with the power of words, imagery, myth and history, missing dinner but no matter.

Anticipating some snowy evenings by the fire, I will buy another copy of this lyrical story, as well as a fine single malt and Ondaatje’s new novel, Warlight (Jonathan Cape), set in postwar London, a book that will surely feature both transcendent prose and an enigmatic story.

Philip Moriarty, professor of physics, University of Nottingham

My must-read is Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray (Basic Books), a searing, smart and often amusingly snarky insight into just how certain aspects of 21st-century physics – or, rather, certain breeds of 21st-century physicist – have lost their way. Although she focuses on issues within her own field of theoretical physics, her messages about bias and wishful thinking are universal. This is a book that should be read by all scientists. I am eagerly anticipating Angela Saini’s Superior: The Fatal Return of Race Science (Fourth Estate). Her Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong was the well-deserved winner of Physics World ’s Book of the Year for 2017 and her exploration of the pseudoscience that underpins so much of the concept of race is sure to be equally influential.

Gary Saul Morson, Lawrence B. Dumas professor of the arts and humanities (and professor of Slavic languages and literatures), Northwestern University

If you have ever wondered why Russia, with a GDP the size of Spain’s, spends so much to project military power, consult Gregory Carleton’s book Russia: The Story of War (Harvard University Press). He describes how Russians locate their identity in a particular view of war and the Russian soldier. They think of themselves not just as continually invaded but as a power undergoing untold suffering to save the world from evil powers, from the Mongols to the Nazis. A quite different take on the Russian experience will appear soon, the latest volume of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s gigantic novel about the revolution, The Red Wheel. The second part of March 1917 (translated by Marian Schwartz, University of Notre Dame Press), which focuses on the revolution itself, narrates incidents as they shift day by day, even minute by minute. Solzhenitsyn describes the confusion of history as it is really experienced.

Jane O’Grady, co-founder of the London School of Philosophy (who also taught the philosophy of psychology at City, University of London)

If you are fed up with the binariness of emotion theories, read Ruth Leys’ The Ascent of Affect: Genealogy and Critique (Chicago University Press). Refreshingly, she doesn’t start from the view that emotions are visceral, sensation-like and universal or from the view that they depend on meaning, culture and (specifically human) cognition. Instead, she evaluates the development, difficulties and merits of both these two opposed approaches, as well as elucidating the inadequacies of neuroscientific analysis. I look forward to reading my sister Selina O’Grady’s In the Name of God: A History of Christian and Muslim Intolerance (Atlantic). Her previous book And Man Created God: Kings, Cults and Conquests at the Time of Jesus managed to be both sceptical and sympathetic towards religion, and to combine the big theoretical picture with illuminating anecdotes (I’m only being a little partisan!). The new one promises to be fascinating not just on past intolerance, but on the crucial topic of how far Muslim and post-Christian Western values can – in the future – co-exist.

Andrea Pető, professor of gender studies, Central European University

Tolstoy’s opening sentence in Anna Karenina, that “every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”, is definitely true for Susan Faludi’s. The Pulitzer prizewinning American journalist’s In the Darkroom (William Collins) is a not-at-all-conventional family saga. In 2004, she received an email from her father in Budapest, whom she had not seen in decades, in which he informed her that s/he had undergone a sex change operation and changed from Steven (István) Faludi into Stefánie Faludi. The book is a chronicle of the 10 years that started with Susan’s arrival in Budapest after receiving the email and ended with Stefánie’s death. We witness Stefánie gradually letting Susan closer to herself (or rather to a previously enacted self) and learn about the layers of forgetting that had been necessary for her to survive the Shoah, migration, the collapse of her marriage and abandonment by a daughter until managing to find “its own way” of living. Sabrina Ramet’s upcoming book from CEU Press, Collectivist Visions of Modernity, examines the historical examples of Soviet Communism, Italian Fascism, German Nazism and Spanish Anarchism, suggesting that, in spite of their differences, they had some key features in common, in particular their shared hostility to individualism, representative government, laissez-faire capitalism and the decadence they associated with modern culture.

Catherine Rottenberg, associate professor, department of American and Canadian studies, University of Nottingham

These are troubled times in Britain: from the chaos of Brexit to the devastation wrought by the neoliberal austerity policies of consecutive governments. One book that provides much-needed insight into how neoliberalism became common sense in the UK is Jo Litter’s Against Meritocracy: Culture, Power and Myths of Mobility (Routledge). She adroitly shows how the existing plutocracy has mobilised “meritocracy” in order to justify and perpetuate its rule. She also demonstrates how Conservatives and New Labourites have converged around “meritocracy”, thus providing a moral gloss to ruthless neoliberal practices. I am now keen to read Shani Orgad’s Heading Home: Motherhood, Work and the Failed Promise of Equality (Columbia University Press), which analyses the gendered and care-related implications of neoliberalism. Drawing on extensive empirical research, Orgad explores the cultural conditions creating increasingly impossible choices for working mothers. Her book promises to lay bare how these contradictions have compelled many professional women in the UK to give up successful careers to become stay-at-home mothers.

Robert A. Segal, sixth-century chair in religious studies, University of Aberdeen

John Forrester, who was professor of the history and philosophy of science at Cambridge, wrote half a dozen original books on the history of psychoanalysis. He was at once erudite and imaginative. In Thinking in Cases (Polity), he focuses on case studies, for which Freud was so famous. Forrester argues that case studies, far from being limited to the specific examples considered, in fact offer a way to generalisation, which is the heart of science. He applies his view to other fields besides psychoanalysis. I look forward to reading Thomas Albert Howard’s The Pope and the Professor: Pius IX, Ignaz von Döllinger, and the Quandary of the Modern Age (Oxford University Press). This examines the bitter dispute between Pope Pius IX, who opposed modernism and instituted the notion of papal infallibility, and the Munich theologian Ignaz von Döllinger, who sought to bring the Catholic Church up to date.

Adam Smyth, professor of English literature and the history of the book, Balliol College, University of Oxford

I greatly enjoyed Jeffrey Ashcroft’s Albrecht Dürer: Documentary Biography (Yale University Press). This two-volume door-stopper isn’t a conventional study of the artist, and it isn’t a narrative: it’s a meticulous record of all the textual traces of Dürer’s life (1471-1528). It’s a book that feels like an archive: you can wander around in it. Right now, I’m editing Pericles, by Shakespeare and (probably) George Wilkins, so I’m particularly looking forward to Mark Haddon’s novelistic reworking of the play, The Porpoise (Chatto & Windus). Over the years, Pericles’ fortunes have gone up and (more often) down – Ben Jonson called it a “mouldy tale” – but I’m hoping Haddon’s novel will catalyse new interest in this strange, stark, unsettling play.

André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London

I am reading Adam Tooze’s Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World (Allen Lane). In this thick book, a historian of modern Europe turns his eye to the long-running effects of the 2008 financial crisis. He traces what caused the crisis, how it played out in North America and Europe, and how it ended up fuelling the rise of populism. It is the first book that tells the whole story from the collapse of Lehman Brothers to the election of Donald Trump. On a recent trip to Texas, I picked up Jill Lepore’s new book These Truths: A History of the United States (Norton). I love Lepore’s writing in The New Yorker, and the book is pitched as a major standard history of the US. That made it irresistible.

Hester Vaizey, fellow of Clare College, University of Cambridge

This year, I found Hillary Clinton’s What Happened (Simon and Schuster) a really engaging read on a number of levels. It was fascinating to gain a sense of what it was like to put so much effort into a campaign and then to lose. It was interesting to read Clinton’s reflections on how her experience as a presidential candidate was shaped by being a woman, and I found the chapter on Russian interference in the US election absolutely staggering. Next year, I am looking forward to Time and Power: Visions of History in German Politics, from the Thirty Years War to the Third Reich (Princeton University Press) by Cambridge’s current Regius professor of history, Christopher Clark. It looks at history with a particular emphasis on the concept of time and should therefore offer a new and thought-provoking way to examine the past.

Simon Young teaches at the University of Virginia Program in Siena

Good British fairy books are uncommon and so I have been excited by Francis Young’s Suffolk Fairylore (Lasse). The title might suggest a tedious trawl through well-known texts. But Young (no relation) has written on Romano-British fairies, medieval “Jewish” fairies and the bizarreries of modern fairy experiences. Very few historians cover two thousand years with this kind of aplomb and I even enjoyed the author’s several disagreements with me. Suffolk Fairylore is just out, but I read Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (Allen Lane) at the end of summer and am still depressed. Tragically, the very idea of freedom of speech is coming under sustained attack in our universities. A psychologist and a lawyer have teamed up to give us advice on how not to get maced on campus while keeping reasoned debate between parties alive.