Browse the THE Japan University Rankings 2019 results

National initiatives to boost the global outlook of Japanese universities are finally starting to pay dividends, according to data from Times Higher Education’s latest ranking.

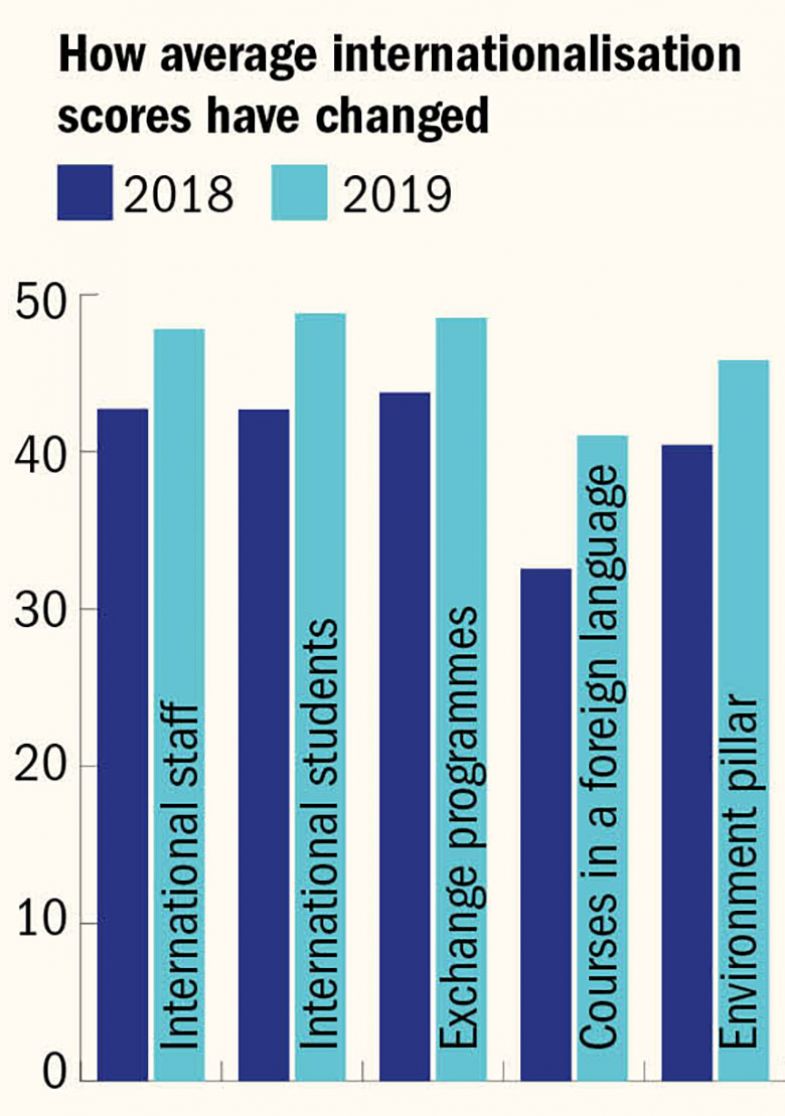

Data from the 2019 THE Japan University Rankings, published on 27 March, show that large numbers of institutions have improved their performance in key areas such as their share of international students, international staff, exchange programmes and courses in a foreign language.

Internationalisation is often cited as one of the main weaknesses of Japan’s higher education system, and improving in this area has become an urgent priority because of the country’s declining youth population and its large debt.

The Japanese government has implemented several projects aimed at stimulating internationalisation in higher education since the early 2000s. These include the £52 million Top Global University project, which launched in 2014 and provides additional funding for the hiring of foreign and expatriate academics, the recruitment of international students and the creation of English-medium degree programmes at 37 institutions.

Comparing figures for the 216 universities that submitted data to both the 2018 and 2019 editions of THE’s Japan rankings, half reported an increase in the proportion of international learners in their student body, while only 42 said that the percentage had decreased.

One hundred and two providers reported a rise in the percentage of foreign staff at the institution, while there was a dip at 62; and 99 campuses reported an increase in the proportion of courses that were taught in a foreign language, compared with 49 that reported a decrease.

Although more evenly balanced, progress on the proportion of students taking part in international exchanges was also evident, with 92 providers reporting an increase and 78 reporting a decrease.

THE Japan University Rankings 2019: the top 10

| 2019 rank | 2018 rank | Institution | Overall score |

| 1 | 1= | Kyoto University | 82.0 |

| 2 | 1= | The University of Tokyo | 81.9 |

| 3 | 3 | Tohoku University | 80.2 |

| 4 | 5 | Kyushu University | 79.5 |

| =5 | 6 | Hokkaido University | 79.3 |

| =5 | 7 | Nagoya University | 79.3 |

| 7 | 4 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | 79.0 |

| 8 | 8 | Osaka University | 77.9 |

| 9 | 9 | University of Tsukuba | 77.5 |

| 10 | 12 | Akita International University | 76.7 |

There is little correlation between universities’ overall rank and their internationalisation improvement. But, in general, national universities receive higher environment scores than private or municipal public institutions, while universities founded before the Second World War are generally stronger in this area than their younger counterparts.

Annette Bradford, associate professor in the School of Business Administration at Meiji University and an expert on international higher education, said that the ranking findings were “a very welcome development” that might, in some cases, reflect the “large-scale government funding schemes for internationalisation”.

“Many universities have been working hard towards internationalising their campuses, curriculum and student body,” she said.

Futao Huang, professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, said the results suggested that “efforts made by the government, individual universities and colleges, and industry, as well as private foundations, in this regard for the past decades have come to be effective”.

However, he continued, Japanese universities must introduce “more flexible teaching and learning systems” to make it easier for students to find jobs abroad, and institutions must adopt a “more flexible policy of hiring international academics, in terms of job contracts, tenure, salaries and pension systems”.

“Individual universities [must] provide more supportive policies…for international academics, especially [those] coming from Western countries who cannot speak Japanese,” he said.

Akiyoshi Yonezawa, director of the Office of Institutional Research at Tohoku University, said that unlike many other nations, Japan did not have a market-driven or commercial approach to internationalisation, and its universities were implementing initiatives aimed at increasing their global outlook as a result of pressure from the government, university rankings or domestic students demanding international experiences.

While this has its advantages, Japan will need to “enter such a market-based competition” in order to recruit global talent for research and teaching and to continue to improve on internationalisation, he said.

But James McCrostie, associate professor in the department of business management at Daito Bunka University, said that it was “definitely too soon to celebrate”, claiming that “much of the government push to internationalisation seems related to the 2020 Olympics”.

“Only time will tell if the bureaucrats’ attention span lasts beyond next summer,” he said.

He added that the Japanese government has cut the scholarship money available to foreign students, meaning that there is now funding available for just one in 315 students, compared with one in 14 students in 2011.

“The nationalists decided not to spend Japanese taxpayer money on foreigners and to spend that money on scholarships to send Japanese abroad instead. But most of the increase in Japanese going abroad has been in short-term, one-month [trips] abroad during spring and summer vacations,” he said.

“The only way real progress will continue is if universities and the government work together. That means ensuring that Japanese students are able to survive in an English academic environment and that solid Japanese as a second-language programmes are put in place.”

Japanese universities ‘fail to take on student feedback’

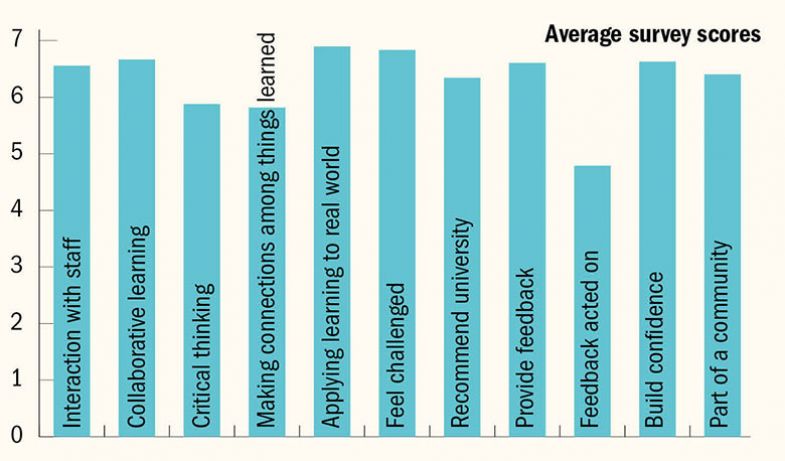

Japanese students generally feel challenged by their university and believe that they are able to apply their learning to the real world, but they think that institutions are poor at taking on board their feedback.

These are the main findings from Times Higher Education’s first Japan Student Survey, which asked students to rate elements of their learning experience at their university on a scale of zero to 10, where zero represented no support and 10 represented being fully supported.

Respondents gave the highest average score, 6.9, when asked whether their institution supports them to apply their learning to the real world. They also rated their institutions highly on the extent to which they feel challenged by their classes (6.83).

When it came to their ability to make suggestions or to provide feedback on a course or on management, students awarded an average score of 6.61, but this fell to 4.79 when they were asked to what extent their suggestions have been acted on.

Universities’ support of critical thinking skills (5.88) and in helping students reflect on, or make connections among, things learned (5.82) were also rated relatively poorly by students.

The survey ran from August to November 2018 and received almost 37,000 responses from more than 400 Japanese universities. It included 11 questions on elements of learning engagement at universities, seven of which are used as metrics in the engagement pillar of the THE Japan University Rankings 2019.

Futao Huang, professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, said that Japanese academics tended to spend more time on research than on teaching and that the vast majority delivered lectures instead of using “other more diverse instructional methods”.

“New ideas such as learning outcomes, active learning and student-centred activities…have been introduced in Japanese universities only in recent years but have not been widely accepted,” he said.

He added that while student feedback has been implemented in many universities, there is little evidence to show that the responses have been used to improve instruction.

Private universities, which account for more than 70 per cent of Japan’s higher education institutions, “place more emphasis on their institutional mission, academic beliefs, importance of disciplines and rigid sequence of curriculum rather than diversifying needs of students,” he said.

However, Annette Bradford, associate professor in the School of Business Administration at Meiji University, said that she was not surprised by students’ low scores in this area “given that changes may not be made until after they have graduated from a course or institution”.

Note: The analysis was based on all universities that submitted valid data. However, the THE Japan University Rankings include only institutions that are in the top 150 overall and/or in the top 150 in any pillar, which amounts to 213 institutions in the 2019 edition.

后记

Print headline: Japan's window on the world widens