In recent years, there has been a renewed focus on teaching in universities. After years of teaching seemingly being relegated to second place behind the priority of research, efforts are being made to level the playing field.

One of the aims of the UK’s teaching excellence framework was to redress the balance between teaching and research. In Australia, senior sector figures have called for a TEF-like scheme to put rewards for teaching on a par with those for research.

According to the UK's Higher Education Policy Institute, academics specialising in education are paying an unprecedented amount of attention to “what works” in the teaching of schoolchildren, “but there is less attention paid to the question of how best to teach university undergraduates”.

A seminar organised by Hepi and AdvanceHE aimed to address this question, asking what universities can learn from improvements in school-level education. Speaking at the event, Helen O’Sullivan, pro vice-chancellor for education at Keele University, said there was a definite need to focus on evidence-based policy on teaching in universities, especially as the higher education sector enters “bumpy ground”.

“We are starting to recognise good teaching at universities but it is slow and there is an awful long way to go,” she said. There was a lot to learn from schools, especially as universities do not have the luxury or resources to “reinvent the wheel”, she added.

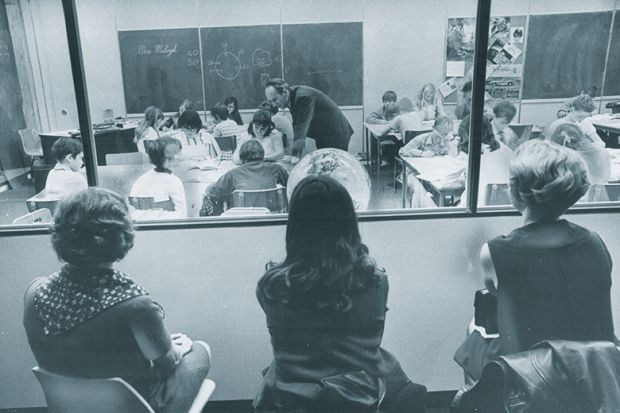

In schools, “things like class size, regular feedback, teaching qualifications: these really have an impact on the quality of education, and there are clear parallels”, she said. “One of the things we need to think more carefully about is feedback, especially at the beginning, as students transition from school to university, and how that helps students. That is one of the things [universities] tend to fall down on.”

“In a school, the teacher really knows their pupils and can give them personalised feedback; that really helps with the development of the student all the way through”, Professor O’Sullivan continued. These are areas where artificial intelligence or other technologies can actually help, she added. “If our small group teaching is concentrated on helping the students, then we can use technology to help with other parts – it becomes almost like personalised learning."

Professor O’Sullivan added that another way of learning from schools was through the idea of comprehensive education. “I find it really odd that, for the most part, those involved in higher education reject the notion of selection at the age of 11 to 16, but happily embrace it at 18,” she said. “Evidence shows that achievement at 18 relates to the type of school that you went to and the economic advantage you've had throughout your life, yet we enforce strict selection at our top universities and in subjects such as medicine.

“If we were prepared to challenge the learning and teaching methods we employ at universities and really think about making mixed ability teaching in universities as successful as it is in many of our schools; wouldn't that have an interesting impact on social mobility?”

Schools have also developed sophisticated measures of learning gain over the years which universities can learn from, said Professor O'Sullivan. So far, attempts to measure learning gain in higher education have stalled, with the National Mixed Methodology Learning Gain project winding up early in 2018.

Ben Styles, research director at the National Foundation for Educational Research, agreed that the ability to measure learning gain – or “value added”, as it is referred to in schools – was key to driving up teaching standards.

Rigorous evaluation is important, he said. But in universities this is restricted to taking place within individual institutions, as there is no way to compare degrees across universities.

“I don't think it would be too difficult to have a set of common items between different universities’ examinations in order to inject some comparability across assessments. In schools, this kind of equating is done regularly to maintain standards and ensure they are comparable. It doesn’t have to be a standardised test necessarily,” Dr Styles said.

However, Gervas Huxley, a teaching fellow at the University of Bristol, said that the ability to compare schools was a key part of improvements in standards, and the only way to do so in universities would be with standardised tests.

“Without standardised tests, you are up the creek without a paddle,” he said. “The bottom line is universities can and should try to learn lessons from what schools are doing and how schools improve their teaching.”