Jeffrey A. Friedman quotes the great German military strategist, Clausewitz, who considered that “war is a matter of assessing probabilities” and that “no other human activity is so continually bound up with chance”. Chance has, indeed, played a great part in determining the fate of military campaigns throughout history: invasion fleets have been destroyed by storms, alliances rent asunder by the unexpected death of a monarch, and armies decimated by plagues on the eve of battle. The elimination of chance is beyond human capacity, but can uncertainty as to outcome, if it cannot be eliminated, be substantially reduced?

Friedman argues that, when it comes to major initiatives in foreign policy or war, the use of a more precise numerical method of producing probability estimates in making judgements and predictions, rather than the vague estimates so often produced, can reduce fallibility. He would replace the traditional methods of decision-making with what he sees as a more exact system involving what amounts to wider focus groups making use of “probabilistic reasoning” involving logarithmic scoring. The process he favours, exemplified in a dense appendix, seems somewhat cumbersome and would not make for rapid decisions, but would it result in greater certainty or simply replace the “vague” judgements he derides as to an operation’s chances of success, such as “very likely” or “very unlikely”, with probabilistic scores of 80 or 20 per cent?

Friedman’s approach is unapologetically American-centric and somewhat history-light in that his case studies of military initiatives and errors are, apart from a brief assessment of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, drawn from the relatively recent past. Two, Pearl Harbor and 9/11, concern failures to anticipate attacks, while the rest come from the long list of misadventures in US foreign and military operations from Kennedy’s expansion of the Vietnam War to the Iraq War and Afghanistan. Whether the methodology he prescribes could have made a difference is questionable. Some were military successes that failed to achieve long-term goals, suggesting that whether an operation is feasible is not as important as whether its object is. The probabilistic reasoning the author recommends might, or might not, have prevented mistakes, but a better historical knowledge of the history of Indo-China, Afghanistan and Mesopotamia, particularly the fissures in Iraqi society, might well have made a bigger difference.

The case that when planning major initiatives all that is possible should be done to assess the chances of success is undeniable and it follows that innovative methodologies should be adopted, but it is dubious whether probabilistic methodology can do more than supplement good planning based on accurate intelligence to make success more probable. Chance will, however, always play a part even in the best-planned operations. Allied preparations for D-Day were diligent, involving risk calculations, good intelligence and disinformation, but the landings could still have failed if the weather had been worse and the German defenders had not made mistakes.

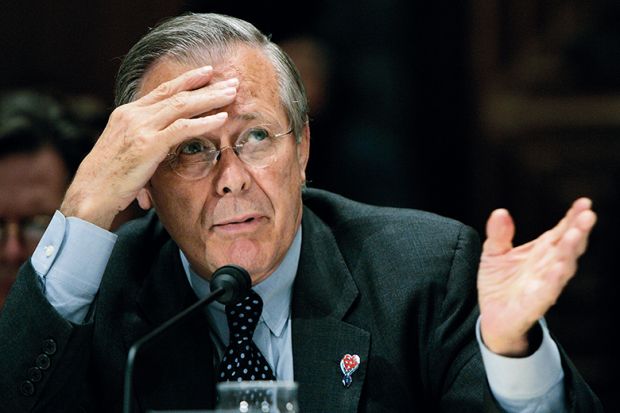

Donald Rumsfeld was widely mocked for his ponderous list of certainties and uncertainties, but one of his categories, “the unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know”, points to a major difficulty in intelligence assessment. Threats we are unaware of can’t be fed into uncertainty or probability calculations, and the arrival of a “black swan” can destroy the best-made plans.

A.W. Purdue is a visiting reader at The Open University.

War and Chance: Assessing Uncertainty in International Politics

By Jeffrey A. Friedman

Oxford University Press

248pp, £22.99

ISBN 9780190938024

Published 30 May 2019