The pay gap between the highest- and lowest-paid staff in universities is greater than anywhere in the public sector, and the head of a government review is calling for a limit to stop the gulf widening.

Will Hutton, executive vice-chair of the Work Foundation, published his interim report on fair pay in the public sector last week.

He had been asked by the government to consider a maximum ratio of 20:1 between an organisation's top and bottom earners.

Of current public sector pay multiples, he writes: "The highest ratio was in higher education, where the median vice-chancellor's salary was 15.35 times the bottom of the Universities and Colleges Employers Association pay spine for university staff."

Among Russell Group universities, that figure rose to 19:1, the report notes. The bottom of the pay spine covers cleaners and porters.

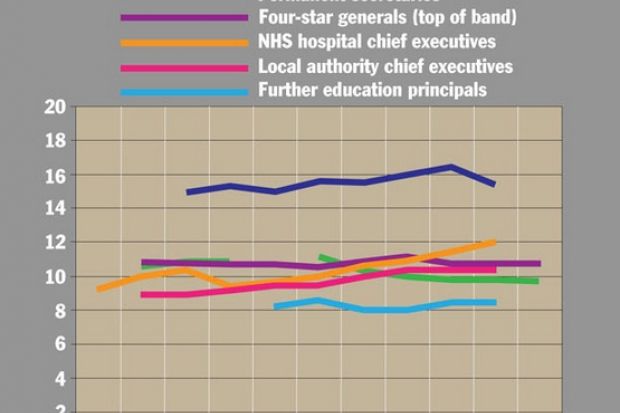

Mr Hutton found that the average annual salary for vice-chancellors stood at £200,800 in 2008.

That outstripped salaries of all other public sector managers, including four-star military generals (£170,800), permanent secretaries running government departments (£160,000) and NHS hospital chief executives (£150,000).

Mr Hutton told Times Higher Education that as universities become more integral to the success of the UK, there will be "more demands on the men and women who run them. Some rise in their pay is justifiable. The question for debate is how much."

Given the slower pay rises for lower-paid staff, Mr Hutton said, there was a question over "how much pay dispersion can continue to go up before it starts to have a distorting effect on universities".

According to the review's figures, pay for vice-chancellors rose by an annual average of 5.2 per cent between 2001 and 2008, compared with 4.9 per cent for those at the bottom of the lowest pay band.

Despite the high salaries for vice-chancellors, Mr Hutton said there was "a very substantial discount to what they would be paid if they were in private organisations with (a similar) kind of turnover".

Although the report finds no examples of pay multiples above 20:1, it warns that some future limit is needed to stop the public sector emulating the private sector "arms race" in executive pay.

In the report, Mr Hutton defines fair pay as being "proportional to individuals' contributions and set by fair pay determination processes".

"As well as being morally desirable, (it) brings...benefits to organisations, by supporting greater employee engagement and morale, and to society...by helping to avoid inequality traps and assisting social mobility and incentives to productive work."

Mr Hutton told THE: "You can imagine that the pay multiple could easily go through 20:1 for all universities. The Russell Group could break it in five years, if not sooner, and you can imagine the rest following through - not in this decade, but the next...Universities need to reflect on that."

Mr Hutton said he was in favour of a "comply or explain" system for the public sector, which would allow institutions to pay more than the maximum multiple if they could "get it past the secretary of state and make a good case for it".

Sally Hunt, general secretary of the University and College Union, said: "For too long, exactly why vice-chancellors enjoyed enormous pay rises and pay-offs from taxpayers' money has been unclear."

Staff received 'excellent' rises, too

A Ucea spokesman said higher education staff enjoyed "excellent" pay awards of 16.4 per cent between 2006-07 and 2009-10.

The Committee of University Chairs, which represents those who set vice-chancellors' pay, said universities were "not-for-profit private sector corporations drawing only 56.4 per cent of income from public sources in 2008-09".

It added: "The ratio of pay between institutional heads and teaching professionals in 2008-09 - 4:1 - is the same as it was in 2001-02."

A spokesman for Universities UK said: "Universities have an average annual turnover of more than £100 million, and are highly complex...The remuneration packages for vice-chancellors are agreed by independent remuneration committees and reflect what it takes to attract, retain and reward individuals of sufficient calibre and experience."

Mr Hutton said universities would be covered by the recommendations of his final report, scheduled for publication in March 2011. "I would say that universities are quint-essential public institutions and always will be, however they are funded," he said. "What they do is of enormous public importance."