The citadel of psychiatry has withstood several determined assaults since at least the middle of the last century, most of them launched from within psychiatry itself. Minor skirmishing, involving a variety of foes, has taken place almost continuously beneath its battlements throughout that period. If reason had been the arbiter of these conflicts, the citadel would now be a smoking ruin, but (as I conclude below) other factors have been, and will probably continue to be, at play.

In this book, Richard Bentall attempts to mount a major new attack from a relatively fresh quarter: that of more or less orthodox academic clinical psychology. One reason he too, I fear, will be beaten back, is that he has no really new weapons in his armoury, and some of the more unfamiliar ones that he attempts to deploy are less than devastating.

The bulk of the book is taken up with pulling together the arguments and evidence that undermine psychiatry's principal claim that mental disorder is necessarily a medical concern requiring medical procedures of diagnosis and treatment. Bentall does this well: it is, for example, hard to disagree with his conclusion, having surveyed the plentiful evidence that exists, that "most psychiatric diagnoses are about as scientifically meaningful as star signs".

He has a deft touch when it comes to summarising, succinctly and accessibly, some of the more complicated technicalities of genetic research, brain biochemistry and statistical analysis (the book is aimed at the "intelligent lay reader" as much as at the interested professional).

Most psychiatric treatments, historically often unconscionable, are these days (usually, of course, in the form of drug treatments) either not effective at all or not nearly as effective as is often supposed; too often they may be harmful. The theories of brain functioning on which they rest are tenuous at best.

As Bentall notes in his historical overview, all these points have been (and are being) made often and powerfully by others. Indeed, in the 1970s it looked as though "the medical model", as we talked of it then, might not survive. But survive it did - if anything, more robustly than before.

A good part of the reason for this, as he explains, is due to the enormously powerful interests of the drug companies, whose influence on research into the effectiveness of treatment has been, and is still, at least as great as their influence on medical practitioners themselves. Again, this point has also been made penetratingly and sometimes courageously by others.

Perhaps the least convincing, or at any rate least effective, part of the book is where Bentall attempts to slide into the place he hopes might be vacated by psychiatry an understanding of mental illness, and an approach to treatment, based on the therapeutic procedures of clinical psychology. Here, however, his erstwhile "scientific" critical standards seem seriously to slip. Whereas, after fairly minute examination, research involving drug trials is found to be wanting, "the quality of psychotherapy trials has often been very good ..." and "the question of whether psychotherapy is helpful has been definitively answered". "The importance of ... factors (such as the 'therapeutic alliance') is now beyond dispute."

Science, as Bentall knows full well, does not answer questions definitively nor make discoveries beyond dispute. And, of course, the field of psychological treatment is hardly less scientifically questionable than the medical procedures of psychiatry.

The contemporary world is such that the model of madness you espouse depends on where your interests lie, and which model prevails depends on the extent of the powers marshalled in its support. But these issues, which raise a host of further questions, are ones that Bentall addresses only partially.

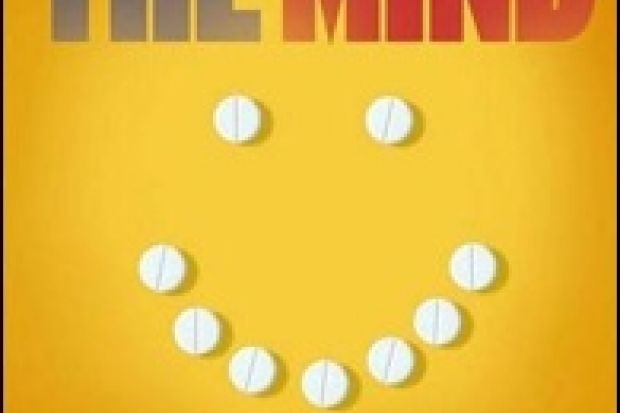

Doctoring the Mind: Why Psychiatric Treatments Fail

By Richard P. Bentall

Allen Lane

304pp

£25.00

ISBN 9780713998894

Published 25 June 2009