In the world of books, "the times they are a-changin'", as Bob Dylan told us. And if bookshops and publishers are going through intense upheaval, this must affect the most compulsive producers and consumers of the written word - academics.

In what economists might call the "value chain" of reading, there are four distinct stages, all of them changing in unnerving but interesting ways. Of course, the process starts with the author, combining two substages, research and then writing; then comes publication which, for both journal articles and books, has historically involved commercial publishers or university presses. Then for books, if not journals, there are the booksellers, the only link in the chain to communicate directly with readers. (Libraries remain an important part of the ecosystem for academic and scholarly works but sadly no longer for general books and lay readers.)

Let's start at the end, with readers, since without them the whole edifice of literary culture collapses. Globally, literacy rates continue to rise and in some markets, such as India, book purchases are soaring as a burgeoning middle class flexes its literary muscles. Reliable statistics are hard to find, but book sales in China are said to be rising fast. Meanwhile, in the US and the West, book sales (including e-books) are growing slowly or are static. So, as long-term trends move in line with the economy, we can expect sluggish growth with the occasional dip in the UK.

However, to the consternation of publishers - and to authors paid a percentage of the cover price or publishers' receipts - prices of physical books are falling and total revenues are declining steeply. This is due to the influence of e-books: much cheaper than physical books, readers have taken to them amazingly. Predictably, the US has leapt first and farthest, the UK coming next, while in other countries a lack of e-books stifles demand. The most popular e-books by far, both in the US and UK, are mass-market fiction genres - such as sci-fi, horror and romance - but skewed strongly towards best-sellers, new titles and price-promoted titles. E-books now constitute between 10 and 20 per cent of all book sales - a percentage that is, as they say sonorously on the shipping forecast, "rising slowly".

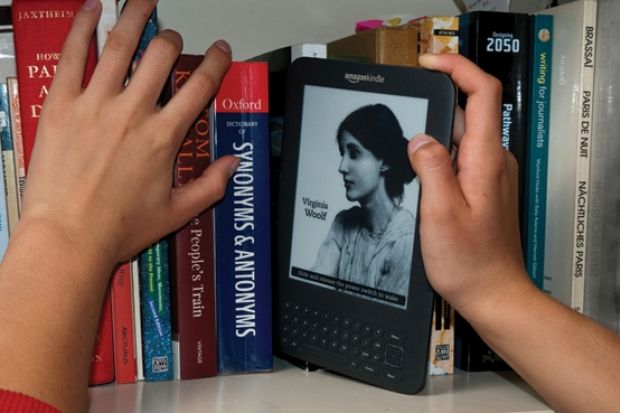

So why are fiction e-books doing better? There is no research evidence but anecdotally there are reasons. One is that many readers do not want to keep old novels, so the physical object (often printed on poor paper) is less appealing than a cheaper and more convenient e-book. Another is that non-fiction e-books don't work as well - indices don't function, references do not connect, one cannot dip in and out easily and illustrations are dismal on the regular Amazon Kindle. Readers either want to own non-fiction books for their shelves or are content to borrow (or read electronically on screen) when prices are too high. E-book sales of academic publications demonstrate "long tail" properties - many titles, but few sales of each.

In December last year, e-book sales dipped, so we may be approaching an e-book and print equilibrium - although it would be an unwise reader who would bet a valuable first edition on that.

One last thought about readers: every generation frets that theirs is the last to read, that the next is too distracted (by silent film, radio, television, video, CDs - remember them? - the internet, social media, Twitter). And so it goes, from one moral panic to the next. The truth is that book-reading has always been a minority activity: in a country of 60 million people, whereas 2.7 million people a day buy The Sun and 10 million watch Downton Abbey on television, a book will easily make it to the top of the best-seller lists if it sells 10,000 copies in a week, often if it sells only a quarter of that. Usually only one book a year sells a million copies - the last to do so was Jamie's 30-Minute Meals in 2010.

Readers may have it better than ever before, choosing between e-books and physical books, with more - and cheaper - titles in print than at any other time. But booksellers, with one important exception, have never had it worse. And it may be terminal. In February, The Booksellers Association said that academic bookselling was facing "unprecedented challenges" and that prospects looked bleak. Borders - the UK's second-largest English-language bookshop chain - went bust in 2009, and other UK independents are closing at a rate of one a week. Barnes & Noble, the biggest book chain in the US (and proprietor of the Nook, the second most popular e-book reader), has seen its profits collapse from more than $200 million (£1 million) in 2008 to a net loss of $65 million last year, and Waterstones, with an annual turnover of about £500 million in 2010-11, changed hands for £53 million in June last year.

The reasons are obvious. First, Amazon now has about 20 per cent of the market for physical books in the UK. It has creamed off sales and with them the difference between profit and loss for many bookshops. And then, just when selling frappuccinos, greetings cards and gifts offered life support, e-books arrived and removed another 10-20 per cent of sales.

And the assault is not over. Free books are another threat. The Project Gutenberg editions of the classics have been much criticised, and when Google's e-library of every out-of-copyright book is fully functioning, it will kill the lucrative sales of classics (including set texts of poetry, Shakespeare and "the canon"). It will probably also reduce sales of stalwarts such as Animal Farm and Lord of the Flies, both of which sell up to 250,000 copies a year as GCSE and A-level set texts, because examination boards will be pressured into selecting free books. No one is predicting anything other than continuing closures of bookshops - although only the gloomiest of doom-mongers think that there will be none left.

Amazon is, of course, another story, although how much money it makes from books is unknown because it is notoriously secretive. It acquired the second-hand book chain AbeBooks four years ago, and Book Depository, the second-largest online book retailer and its only competitor, last year. In the UK nearly 90 per cent of all e-book sales go through Amazon. However, a consumer backlash has been developing against its growing power, most recently demonstrated in late February when it unilaterally removed from Kindle all the books published by 400 independent publishers in the US distributed by IPG because they would not accept the new terms that Amazon was dictating.

Amazon is also intent on becoming a major publisher, having opened an office and hired some expensive personnel in New York. No doubt London is next. But if the titles it is buying in New York - sci-fi, romance and some high-maintenance celebrities - are anything to go by, it won't have much impact on the academy.

All this is making the third cog in the chain - publishers - sweat. Publishers (the more tech-savvy of them, anyway) can cope with the switch from print to e-books, although no one knows how much things such as covers, blurbs and catalogues - stalwarts of the old techniques for selling books - matter in a digital world. On the whole, publishers are making the switch effectively, and profits are swelling because e-books are more profitable (and cheaper) to publish than physical books. So, for example, on February, Penguin bucked sales trends by announcing that global sales were up 1 per cent, but profits were up 8 per cent.

Publishers worry that this may be the last ray of sunshine as the clouds, with or without silver linings, gather. The single largest threat to publishers - and it threatens the whole sensitive ecology of writer, publisher and reader - is price.

Soon, every out-of-copyright book, drawn from collections including the Bodleian, Harvard University Library and the New York Public Library, plus the highly controversial orphan works - those works in copyright whose owners "cannot" be traced - will be available free to anyone with internet access via Google e-books. Google has been trumpeting the service for some years, and despite a drawn-out legal challenge from copyright holders (including those of the so-called orphan works), it will happen in the very near future. That will make copyright e-books seem expensive - hideously so - if publishers try to charge hardback or academic book prices for them.

If books are free to readers, then why not journals too? Open access, much discussed in these pages, is not free. It is now widely acknowledged that someone - author or funding institution - has to pay, if not the reader. This changes expectations as well as publishing models. One immediate result has been the highly effective campaign against the journals behemoth Elsevier, spearheaded by Timothy Gowers, research professor in the department of pure mathematics and mathematical statistics at the University of Cambridge.

One thing is clear, the much-heralded but long-delayed death of the academic monograph is finally upon us. It is still breathing, but under hospice care, with the priests of open access waiting to say the last rites. It is economically more unsustainable than it has ever been to print 250 copies to sell to US university libraries and a handful elsewhere. It has long ceased to be a meaningful act of dissemination anyway: it is not publication but "privification", distributing for the infinitesimally few. It is an anathema when so much, whether archival material, data or research, is now universally available free on the internet.

Last but not least, there is piracy. Authors and their publishers have long suffered from pirated editions of print books in Nigeria, other parts of Africa and China. But with e-books the problem is not a light shower but a deluge. At present the problem is under control, although almost every imaginable title is available on bit-torrent websites, often hosted in countries with weak copyright protection, often before the book is even published, but no one talks about the problem or knows its real magnitude. Although in the UK The Publishers Association has an effective "take-down" portal to serve legal notices to websites hosting copyright-infringing content, as e-books are increasingly read on a variety of tablets and not just Amazon's proprietary Kindle, the problem can only grow; the only questions are by how much, and whether it will exert downward pressure on the price of e-books and therefore physical books.

For the moment, books seem to have continuing life and readers loyally want to pay to own physical and e-books, and publishing continues to be profitable - but everyone knows what happened to the music industry. Publishers are worried and some are haggard after sleepless nights wondering whether piracy will wipe out the book industry too.

More positively, this is an exciting time for authors, who have never had more opportunities to appear in print. The number of books published each year seems to have peaked, but last year more than 149,000 were published in the UK and a large proportion of those must have been by academics. So publishers are not, despite their constant hollow claims, trimming their output. Instead, they are cutting the advances they pay their authors. University presses and academic publishers have always been Scrooge-like but the trade publishers, such as Penguin, Random House and Profile, have been more forthcoming - everyone knows stories of academics getting mouth-watering advances against royalties, sometimes well in excess of £100,000 for a book. When the sums are above £1 million it tends to make the national news. But, for most authors, advances are coming down for all the reasons I have set out, and literary agents, who have been so active on campuses, particularly in history departments, are finding it harder to make a living on 15 per cent of the author's takings and, consequently, are paring down their lists. Anecdotally, where academics were getting £10,000-£25,000 for books a decade ago, they might settle now for £5,000-£10,000.

With the partial exception of blogging, self-publishing is still deeply suspect, not respected and almost shameful. As one would expect, as there is no peer review, almost all self-published e-books are unspeakably appalling. There are close to 2 million self-published e-books on Amazon, although an unquantifiable proportion is pirated, computer-generated by bots or defamatory. A tiny example: Profile Books publishes Susan Hill's chilling ghost story The Woman in Black in hardback. But search under that title for e-books on amazon.com and screeds of stuff comes up, most of it racist pornography of one revolting variety or another.

Although this seems to leave authors and academics with few options, this will change. It is easy to imagine groups of academics creating semi-open communities to publish specific datasets, research or even full-length books, and in doing so bypassing conventional publishers. The first step is to sort out the review process and develop the reputation for quality that publishers have so assiduously fought for over decades. Green shoots, such as Anvil Press in Canada or Open Book Publishers in the UK, are already sprouting, although how the financial models will work, without more charitable support and donations, is far from clear.

For most academics, the chance to be reviewed, edited, marketed, sold internationally and perhaps translated into other languages remains the most attractive option, which means knocking at the door of conventional publishers, even if they are changing everything they do.

Things might look grim, but reading and writing will continue unabated and the prospects are exciting, if challenging. As Dylan put it:

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won't come again

And don't speak too soon ...

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times, they are a-changin'.