Ministers, vice-chancellors and educational fashions may come and go, but some things stand the test of time in British higher education. This week marks the 30-year anniversary of one of the most popular institutions in academe: the University of Poppleton.

The Don's diary, which developed into Laurie Taylor's celebrated column, was dreamt up over a drink with Brian MacArthur, editor of what was then The Times Higher Education Supplement. MacArthur was an ambitious all-round pressman for whom covering the university sector was just a staging post in a wide-ranging and distinguished career.

"He was first and foremost a journalist and working in the Times building," recalls Taylor, "so it felt as if he was in an alcove away from where 'the real journalism' was going on. I think we got on because he found the constraints of higher education a bit wearing, as I did, so he was quite glad to find an academic who was something of a kindred spirit. He was keen to find someone within the institution to mock it."

Taylor proved to be the perfect choice. Although he was already professor of sociology at the University of York, he was a maverick, by both temperament and training, who brought an amused outsider's eye to the foibles of the sector. Much of his background feeds into the column.

In Articulated Laurie, the one-man show he used to take around universities, Taylor described what it was like to take up his first academic post in 1965. "I'd never really been to a university myself," he explains now. "I went to Birkbeck in the evenings, when there was no institutional, social or community life. So I hadn't the faintest idea about what one did. I sat in my room [at York] for several weeks and nobody came to see me to tell me what to do."

Eventually somebody turned up and the following dialogue ensued:

"How are you getting on?"

"I'm fine, thank you very much. But I don't seem to be doing much."

"Would you like to do a bit of teaching?"

"Fine."

"How many hours a week would you like to do?"

"I don't know, I haven't thought about it - six?"

"Take it easy! That's twice the departmental average."

A former actor, Taylor soon started to give flamboyant first-year lectures, with lots of jokes and arm-waving, attracting much attention within the university. This suited him fine: "As long as I was a popular lecturer, I didn't have to do any research or attend any committee meetings."

These early days at York were also marked by his involvement in the National Deviancy Symposium, which held 13 major conferences between 1968 and 1973 (and was eventually wound up in 1979). It was run by a group of radicals who viewed most criminologists as agents of the state who were concerned only with eradicating crime, while they saw it as their job to understand it.

This led, according to Taylor, to "an enormous proliferation of ethnographers who went around living in deviant gangs, hanging around with football hooligans or other low-down disreputable groups. I spent time in the maximum-security wing at Durham Prison with John McVicar, the Kray brothers and Ian Brady (the experience resulted in the book Psychological Survival, co-written with Stanley Cohen) - that was absolutely par for the course.

"There were so many of these ethnographers ... When one of the group, Mary MacIntosh, arrived at Waterloo Station one night, she saw a huddled, crumpled figure on a bench who said, "Night, Mary!' and she realised it was one of her colleagues doing participant observation among down and outs.

"The deviancy symposium provided an extraordinary anarchic forum. A great deal of drugs were consumed by people doing work on drug-takers. A university duck was beheaded one night. And this became so notorious we had to rein it in and decided to call a halt and put all the remaining money on a horse - which lost."

At this point, in an attempt "to pull the deviants in a bit", Taylor was wooed by the sociologist A.H. Halsey to take up a position at All Souls College, Oxford. Taylor said he felt out of place in Oxbridge, but Halsey reassured him, saying: "I'm a working-class boy; you don't have to go up to high table to be waited on. We'll just go to any old pub."

So they went to a pub, which looked perfectly normal, got in the drinks and Halsey asked Taylor what he wanted to eat. Taylor asked for a cheese roll. "So he went to the counter," Taylor remembers, "and asked for two cheese rolls. And the barman said, 'Certainly, sir. Your usual smoked Austrian?' A smoked Austrian cheese roll! I beat a retreat and never ventured outside York again."

Progress up the career ladder came when a new professor, Roland Robinson, joined the department at York. Taylor worked out an elaborate plan to secure his professorship, which involved openly flirting with Robinson's wife at the initial meeting, but they soon became firm friends after his new boss told him: "You're wasting your time being the buffoon in the department. I've read some of your stuff - why don't you try harder?"

Promotion to a professorship finally came in 1974. "Suddenly I was there on professorial and appointments boards. Suddenly I was pronouncing on ethical matters," he recalls.

This was sometimes seen to be at odds with his role as a satirical columnist. "Nothing terrible happened, but I was taken to one side by a philosopher on the croquet lawn once and told: 'Laurie, I only want to give you one small piece of advice - don't bite the hand that feeds you!' And then he sloped off. So I did have that slightly hanging over me."

To a large extent, Taylor conducted his social life outside the university. "I used to hang around with people from the town - and in the 1970s you could also hang around with students. I had one or two footballing mates."

Yet he was also "hugely encouraged in everything I did by a few genuinely eccentric academics. There was the wonderful Peter Sedgwick in the politics department, who would give lectures on fascist history dressed up as Mussolini. There was Wilfrid Mellers, the famous professor of music, who announced to an astonished group of first-year students about the climax of a Shostakovich symphony: 'When I hear that, I find it impossible not to come.'"

It was the deliberate policy of Lord (Eric) James, the first vice-chancellor of the university, "to appoint exciting, interesting professors". Many of whom proved quite impossible to control.

"They were always upsetting the apple cart, always doing the most appalling things. Harry Ree, professor of educational studies, went on the evening news one night and said all foreign languages should be abolished in schools because people who wanted to learn them could acquire the knowledge in six weeks after they had left. If you think about how much French most children manage to learn after five years in school, he said, one is driven to the hypothesis that they'd been given classes in how not to learn French.

"There was also the economist Jack Wiseman, who was a monetarist before Thatcher came along. He had a slightly high-pitched voice and tended, in all meetings, at almost any point in the conversation, to call out, parrot-like, 'Market forces! Market forces!'"

Although it was obvious why Wiseman was known as "Market forces", it took Taylor some time to discover why he had also been given the nickname "Keats and Shelley". This came from his belief that academic questions had to be strictly relevant - somebody who had given a paper on Keats shouldn't be asked about Shelley. If some hapless undergraduate asked a visiting economics lecturer an inappropriate question, Wiseman would leap up and scream mysteriously, "Keats and Shelley! Keats and Shelley! Next question."

Taylor recalls such characters with great fondness. "I loved them and spent a lot of time with them - they were great to be around. But they wouldn't be tolerated now. There are no points for eccentricity in the research assessment exercise."

Taylor's delight in mavericks and outsiders extends well beyond the academy. Even within sociology, he feels, his background - Catholic lower middle class - put him in a somewhat anomalous position. "You had to be either working class or rather grand middle class.

"Lower middle class defines itself as 'not working class' but doesn't really have its own culture. You watch out for what the working class does and don't do it - it's hardly a recipe for a progressive culture! There were many working-class people in social science, but they felt they had a right to be there, since sociology was about transforming society in its early years."

An early mentor, Anthony Giddens, introduced Taylor to the work of Erving Goffman, including Asylums, a study of closed institutions and how they operate. "It's full of nicely ironic observations of how they are always run for the benefit of the managers rather than the patients, clients or whatever ... I was inclined by virtue of this reading to think there was something comic about closed institutions, how they manage to develop a rhetoric of self-justification, how they are managed - despite the declared aims and objectives - to ensure that the staff have an easy life. And when I arrived at universities, they certainly were!"

Such traits can be found in Poppleton's very own Dr Piercemuller, whom his creator "always rather liked as a character", although Taylor says he now belongs to a long-lost world.

"The idea of an academic who spends his time wandering round the world and doing no work - there aren't any left! So I have to keep him almost quiet. When I reprise him it's for the sake of reprising him, not because he has any more satirical relevance."

Although Taylor twice attempted to write popular sociology books, he says: "They turned out not to be popular but striving so hard to be popular as to earn condemnation from the academic establishment ... I wrote one book with Roland Robinson I still can't understand! I occasionally take it down and try to read it, but I still can't make head nor tail of it!"

He likes a book he wrote with Stanley Cohen called Escape Attempts: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Everyday Life (1976 and 1992), which stemmed from their work in prisons and expanded "to talk about escape from institutions like family, marriage, universities, jobs".

He also wrote In the Underworld (1984), after "spending time hanging out with John McVicar and talking to professional criminals - few criminologists had done that before".

So what were they like to spend time with?

"They're irresistible, because they're on the edge. They always want to be on the inside track, to know what's going on. They always want to be one up on the straight world. It was easy to become over-romantic; that was the thing you had to be careful about. Some sociologists totally overstepped the mark and became quite unreasonably romantic about people who were hurting, harming and terrorising other people.

"But somehow when you're in their presence and they're talking, because of their disregard for every rule or form, I would defy anyone not to be entranced by them - apart from the (relatively few) gangsters, the ones who actually like violence."

For anyone frustrated by "the inability of academics to make their mind up", there was also something very refreshing about criminals.

"It's always black and white in that world. It's quite straightforward: 'he's fucking out of order' or 'he's all right'. There aren't any liberals. (You don't often hear things like) 'well, I'll say this for him' or 'but on the other hand'."

Although he retired from his York professorship in 1993, Taylor continued to visit universities with his Articulated Laurie show, and he interviews several social science academics each week on his Radio 4 programme Thinking Allowed. (Envy and snobbery meant that his colleagues treated this radio work as "something that shouldn't be mentioned in polite company, as though I'd been away at some satanic sex fest".)

Furthermore, he says for the past eight years he has received "lots of scurrilous emails, sometimes three or four a day, with major three-page documents written by vice-chancellors, sent anonymously as further evidence of the absurdities of organisations". The most spectacular examples get noted down.

Despite all the gags and comic exaggeration, Taylor clearly feels that things have gone radically wrong within British higher education - and he isn't always impressed by the responses of academics.

"There's been a real diminution in research freedom," he argues. "It's meant that a whole branch of anthropology and ethnography, where researchers spent two or three years with a group of people and came back with some inside story of their lives and culture, is now almost impossible.

"You get vapid little bits of research, which take six months to do and amount to little more than rejigging common sense, or you get people churning out orthodox research in areas approved of by the ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council) ... There's not much surprise in a lot of the research I come across now. It hugs the mainstream, because it doesn't have a licence to roam."

The university system he joined was "slack and indulgent", Taylor readily admits. "Some people did no research at all. Holidays began at the end of June and went on to the second week of October. People would gaily plan eight-week holidays. But to deal with the fact that some research money given to universities wasn't being used, that some academics were having an easy life, they built this absurd top-heavy, quantitative, tick-box culture operating from the centre that produced so many anomalies and absurdities and in the end utterly perverted the culture of universities in terms of research, policy and teaching.

"What made me angry was the way in which serious intellectuals, who were supposed to be self-reflective, intelligent and to have a nice sense of irony, rolled over in the face of the new managerialism.

"To see people whose intelligence you've admired, whose books you've admired, mouthing this lickspittle jargon - that still makes me angry, to see grown intelligent human beings falling quite so readily for this mumbo-jumbo nonsense." Genuine outrage underpins Taylor's portrait of Poppleton's Director of Corporate Affairs, Jamie Targett, and all he represents.

Some may put this down to continuing nostalgia for the academic playground of the 1960s. But Taylor believes that the enthusiastic response to his column points to a genuine malaise within universities.

"I feel now, as I didn't feel before, that I might be performing a mildly therapeutic function. In the past, people would say, 'Very funny! We stuck it on the wall.' It used to be more amiable and make people smile, but now everyone has their Jamie Targett and I can provide not just a laugh but a psychological or rhetorical weapon to employ against him.

"People say, 'I couldn't have got through this without Jamie Targett. I stuck the column up on somebody's board - and he realised.' At times it may have been excessively whimsical, but now I'm slightly more conscious of the number of people who need their ammunition, even if it's only psychological ammunition, against the management."

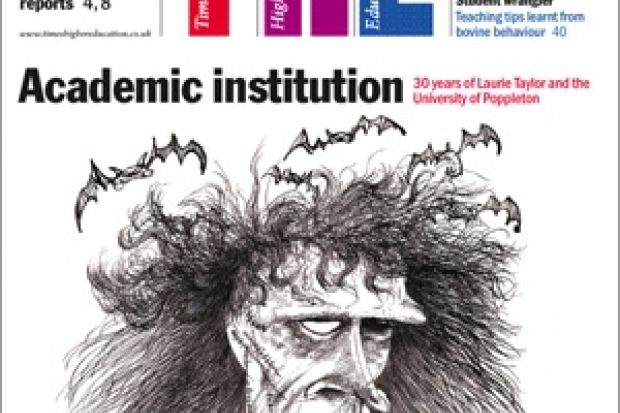

And, finally, what about the dramatic image of Taylor that accompanies every episode of life at Poppleton? When he started work on the series, Taylor's then wife Anna Coote suggested that Ralph Steadman should create a cartoon from photographs. But she didn't like the result and sent Taylor to demand improvements.

"I took the rolled-up copy to Steadman's house in Fulham," he recalls. "My wife, I said - sheltering behind her immediately - feels it's not quite right. So he said, 'Come with me, then.' He unrolled it on his easel and immediately put a bolt though the neck and bats flying round the head, and gave it back saying, 'See if that's any better!'

"On the way out, he said, 'Perhaps every time you look at it you'll be tempted to be a little bit more daring.' I don't think I could ever manage to live up to the mad genius of Ralph Steadman, but occasionally when I've wondered whether I can really be so outrageous I have glanced towards it and thought I can't be mealy-mouthed."

As we toast Taylor's first 30 years on the job, we can only add: long may he continue!

SOCIOLOGIST, POLITICAL MORALIST AND FRIEND: PRAISE FOR TAYLOR

I am asked to pay a brief tribute to Laurie "as a sociologist" and "as a friend".

The problem is not just that these subjects are too large for such a restricted space. My worry is the word "as". This makes the request sound like a student assignment to write an essay about Muhammad Ali "with particular reference to his life as a boxer". Being a sociologist and being a friend are what Laurie does. They make up a large part of his life.

The standard praise of Laurie as a sociologist is justified - his ability to absorb (and, moreover, evaluate) complex ideas and to represent them to wider audiences without a trace of condescension is well accepted. His successful move from academic life to journalism is more grudgingly acknowledged. Too much of a performer for dull academics, so the script goes, he now has gravitas because those around him are shallow media types.

Such horribly cliched comparisons are the main enemy in Laurie's life and work. He has a particular talent for sniffing out the combination of mediocre and pretentious (a talent totally absent in the iconic world of Poppleton - which is just his point). His battle against cliche is radical and extreme. Armed with a literal reading of labelling theory, he resists not only being labelled, but labelling others. That's also what makes him do well "as a friend".

Stanley Cohen

Emeritus professor of sociology, London School of Economics

Laurie Taylor is plainly the funniest satirist of academic life in our time; he is also a political moralist of absolute probity and high seriousness.

If one takes, as one should, the immortal column as being a single work of art, like a novel, one finds not only an incomparable range of intensely realised characters (Lapping, Piercemuller, Maureen and the appallingly recognisable v-c) but also the most poisonous and life-destroying tendencies of contemporary university practice made at once vivid and revolting.

Above all, he makes the claims of managerialism to intellectual merit and administrative competence both laughable and contemptible, and does so with tearing high spirits and hardly a tremor of exaggeration.

But his true subject is the threat facing us all in the attempt to keep up ideals of scholarship and pedagogy - the veneration of mere money.

Taylor's bitter jokes at the expense of this obsession are his great achievement and make his peculiar brand of political sociology as important as the work of C. Wright Mills or Richard Titmuss.

Fred Inglis

Emeritus professor of cultural studies, University of Sheffield

TOP MARX FOR THE DON'S DRY WIT

Extract from Laurie Taylor's occasional Don's Diary, which led to the commission for the Poppleton column

Very pleased to find an invitation to visit Market Harborough College of Social Studies in my morning mail. Not on the face of it an ideal venue, but they're doing some excellent work these days at the college. Most of it is due to a chap called Turpin ... Faced with the usual indifference to sociology by first-year students, he hit on the idea of dramatising some of the classical works. Last time I was there I adjudicated a very commendable version of Ralf Dahrendorf's Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. The whole debate took on a new edge when you actually saw Mosca, Pareto and Marx arguing their cases up there on the boards ... On the sides he'd erected three rostra which accommodated the separate choruses - The Rising Middle Class, The Nineteenth Century Working Class and a smaller section who of course represented Dahrendorf's famous Imperatively Co-ordinated Associations. I was very sceptical before I went but came away convinced. I see they're having a shot this year at Marx's Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. Turpin certainly loves a challenge.

The Times Higher Education Supplement, 28 November 1975

DRAMA, DEVIANCE AND DEADLINES: PRESENTING LAURIE TAYLOR

Laurie Taylor was born in Liverpool in 1936 and educated at Catholic schools. He initially trained as an actor and formed part of Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop in Stratford East. He also worked as a sales assistant, librarian and English teacher.

As a mature student, he took a first degree in psychology at Birkbeck, University of London. This was followed by an MA in sociology at the University of Leicester, which awarded him an honorary DLitt in 2007. His academic career began when he was appointed lecturer in sociology at the University of York in 1965. He was promoted to reader in 1973 and finally professor from 1974 to 1993.

Taylor's books include Deviance and Society (1971), Psychological Survival: The Experience of Long-term Imprisonment (with Stanley Cohen, 1972), Man's Experience of the World (1976), Escape Attempts: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Everyday Life (with Stanley Cohen, 1976 and 1992), In the Underworld (1984), Uninvited Guests: The Intimate Secrets of Television and Radio (with Bob Mullan, 1986) and What Are Children For? (with his son Matthew Taylor, 2003).

He is also an experienced journalist who, in addition to his 30-year Poppleton slot in what is now Times Higher Education, wrote a New Society column for ten years and a New Statesman diary for five. He still works as commissioning editor at New Humanist, contributing profiles and the regular Endgame column. There have been three compilations of his Times Higher Education pieces, starting with Professor Lapping Sends His Apologies (1987).

His extensive radio experience included regular appearances on Robert Robinson's Stop the Week. He now presents the weekly discussion programme Thinking Allowed on Radio 4. His television documentaries include Crime: The Shocking Truth (BBC Two, 1973), Roll Your Own Revolution (BBC Two, 1978), On Pain of Death (Channel 4, 2005) and A Very British Apocalypse (Five, 2007).