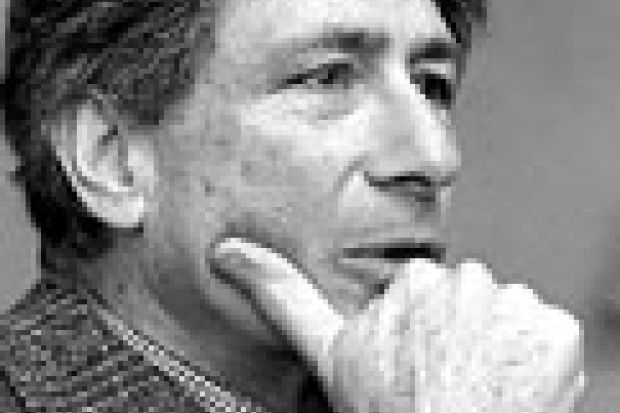

Palestinian intellectual Edward Said recently visited South Africa to advise on education, but while he was there he also spoke of how the country had much to teach the Middle East about the pursuit of democracy and peace. John Higgins reports.

It is possible to imagine that there are two very different people who happen to share the name Edward W. Said. The first is a distinguished professor of literary criticism from Columbia University in New York, the author of books about such rarefied writers as Joseph Conrad, James Joyce and Marcel Proust. This Edward Said is an urbane, cultivated aesthete, the product of the best that western education and culture has to offer, an academic who is also, in his spare time, a talented classical pianist and a devoted lover of opera.

The other Edward Said is a militant Palestinian intellectual, author of controversial works such as Covering Islam (a study of how western media offer only distorted and stereotypical representations of Middle East people and politics) and The Politics of Dispossession , an impassioned account of the ongoing Palestinian struggle for self-determination. This Said is the scourge of US foreign policy and global imperialism, someone hated and feared by the Israeli government and its polemicists for whom he is - in the words of one pamphlet that tends to appear in large quantities wherever he speaks - the "Professor of Terror". In reality, of course, the two Saids are one and the same.

Said was recently in South Africa to give a keynote address at a conference on educational policy. The conference was convened by minister of education Kader Asmal and held in the lush setting of Kirstenbosch Gardens over a swelteringly hot Cape Town weekend at the end of February. In a spellbinding performance, which attracted sustained applause, Said argued for the importance of the art of critical reading to any democratic society.

While accepting a national need for education in science and technology to make South Africa globally competitive - hitherto the main emphasis of government policy on higher education, as humanities faculties around the country have found to their cost - Said suggested this emphasis needed to be matched by continued attention to education in culture and the humanities. However much of its existence a country owes to its economy, the wellbeing of its citizens depends a great deal on the health of its public culture.

"Even after apartheid," he warned, South Africa could pay a high price for the absence "of a lively and viable intellectual community, one able to deal sceptically and perhaps even subversively with injustice, dogmatic authority, corruption and all the blandishments of power." The training of students in the skills of literacy and advanced literacy is a necessary part of developing a democratic society. "Critical reading," he urged, "provides students with an awakened understanding" and "furnishes the engaged mind with an alertness to the lazy rhetoric and automatic language-use that has so often covered up abuses of power."

After the speech, I asked him whether he feared that this culture of critical reading was under threat and near extinction. Technocrats and academic administrators appear to think that access to the internet, by offering almost unlimited information, can provide the basis for a massification of higher education. The new university has less need than the old for teachers and the in-person teaching experience. "Knowledge and understanding," he pointed out, "will always be different things. You can surf through every newspaper report in the world available in cyberspace, but still walk away as functionally ignorant as when you began. The point of literacy is to develop a more heightened and mobilised sense of citizenship and participation among ordinary people." And this, he believes, is best developed through close reading and face-to-face debate.

"I'm not one of those people who complain that in the good old days, things were different, were better, if only we could get back to that. Sure, things are happening in a certain way now, but they can always be resisted and ultimately reversed. That is why I feel teaching is central to any society. For someone of my age and failing capacities (Said has been struggling with leukemia for the past eight years, though he is still writing and speaking with extraordinary energy and commitment), I see my central role as being that of a teacher. You can teach in a classroom with the sense of satisfaction and immediacy that that can give, and you can teach through writing. I try to do more and more periodical writing to reach a wider audience. It must never be forgotten that the whole idea of education is to change and improve things, so that other cultural and political possibilities can emerge, even at moments when so-called pragmatists say this is impossible."

In another public lecture, drawing on the main themes of his new book about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, The End of the Peace Process , Said issued a moral challenge to democratic South Africans who had opposed apartheid. He began by quoting Nelson Mandela's opening remark at the education conference -that the struggle against apartheid was "one of the great moral struggles of history". Why, challenged Said, did the world not see the ongoing Palestinian struggle for justice and self-determination in the same light? It should be particularly clear to South Africans, he argued, that Israeli policy amounts to little more in its brutal denial of rights and territory, and in the continued violence of its policing and dispossessions, than a particularly virulent form of apartheid. The recent collapse of the so-called peace process only illustrated, for Said, what South Africans know from their own recent history: the fact that "you cannot defeat an entire people, however much violence and persecution you visit upon them".

After 53 years of struggle, "the Palestinians have not given up and we will refuse to give up until justice is done". He closed the lecture by offering his own sense of the necessary conditions for a realisable peace between Jew and Arab. Essentially, these were the very same conditions that had enabled South Africa to make its remarkably bloodless transition from apartheid to the democratic non-racial society it is, or strives to be today. First, there must be a basic acceptance from both sides of the idea of the coexistence of different peoples in a single state. Second, the principle of equality for all citizens under a common constitution has to be accepted. In our discussion, he accepted that it was "fantastically difficult" to make this idea of peaceful coexistence in a single state acceptable to either Jews or Palestinians. But, he stressed, what other grounds could there be for a lasting solution to an otherwise interminable conflict?

Perhaps, in the end, the key to the particular force of Said's writing and personality is his unusual and principled combination of culture with politics, of textual analysis with political engagement. As he put it:

"Whatever I've done politically is entirely dependent on the ability to read critically, to be able to understand the uses to which language is put, its vast range of possibilities. I think the best place to get a sense of this is through the study of literature."

John Higgins won the Cape Tercentenary Award of Excellence for his services to literature and culture in South Africa last year. He is associate professor in English at the University of Cape Town and editor of the journal Pretexts: Literary and Cultural Studies . His Raymond Williams Reader has just been published by Blackwell, £15.99. Edward Said will lecture on Criticism and Exile: the Postcolonial Predicament at London's School of Oriental and African Studies on March 22.