The UK’s Office for Students was launched this month, with more headlines about its mission to crack down on universities that permit the “no platforming” of controversial speakers.

Unmoved by protests from universities that students’ unions are legally independent bodies, Jo Johnson, the universities and science minister at the time, told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Boxing Day that the new sector regulator would fine universities that fail to uphold free speech anywhere on campus.

Johnson had previously expressed the view that in some universities, there are “examples of censorship where groups have sought to stifle those who do not agree with them”. But although there have been controversial applications of no platforming over the past decade by some students’ unions, the tactic remains necessary for its original intended purpose: to prevent openly racist and fascist groups from organising on campus. While there have not been the same mass gatherings of white supremacists on UK university grounds as there have been in the US, such as at the University of Virginia last year, that does not mean that UK higher education is immune.

No platforming is often associated with the similar concepts of safe spaces and trigger warnings, supported by many people as necessary in the fight against discrimination, intimidation and violence, but derided by others, who view the current generation of activists as “snowflakes” obsessed with the paradigm of identity politics.

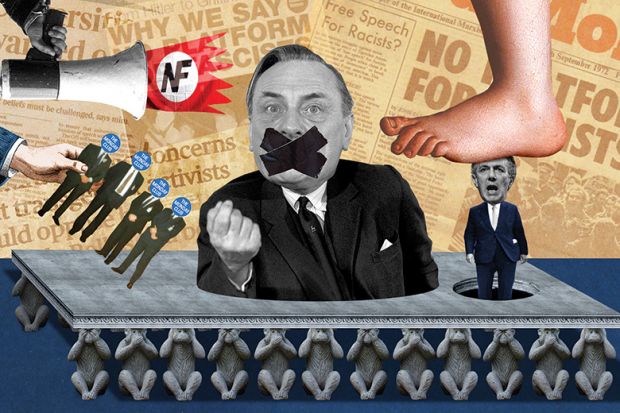

But no platforming is actually far older than those other concepts. It emerged from the British student Left in the 1970s in response to the rise of the violent, neo-fascist National Front, following Conservative politician Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech against immigration in 1968, and the UK’s entry into the European Economic Community in 1973.

The phrase “no platform” was first used in 1972 in the pages of The Red Mole, the newspaper of the International Marxist Group, in relation to preventing the National Front and Conservative right-wing pressure group the Monday Club from campaigning on campuses against the arrival of Ugandan Asians in the UK. The group was very influential in the student movement and a policy of denying a platform to fascists and racists, in the context of protecting international students, was adopted by the National Union of Students in a vote at its 1974 conference. Despite subsequent attempts to remove or alter the policy, it remained in place throughout the 1970s.

In addition to its original anti-racism focus, it was sometimes used to intimidate others, such as when Conservative politician Sir Keith Joseph attempted to speak at the University of Essex in 1977; Margaret Thatcher’s future education secretary was notorious for a 1974 speech in which he said that “the balance of our human stock” was threatened by poor people having too many children.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, there was a concerted push to extend no platforming to other forms of discrimination or hatred. In particular, a number of feminist activists called for the no platforming of sexists. The policy was also used by some supporters of Palestine to prevent pro-Israel student groups from organising on campuses. However, some of those who had argued for the no platforming of the National Front felt that its wider application diminished the original intent of the policy.

In the 1990s, no platforming also began to be used against radical Islamists. Recently, it has been applied to those critical of Islam – and thus deemed Islamophobic by some – and also against people considered to be transphobic, such as the radical feminists Julie Bindel and Germaine Greer, and the gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell (who was also accused of racism). The Tatchell incident, which occurred in 2016, actually involved the NUS’ lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender representative refusing to share a stage with him, so it was not strictly no platforming – but it was depicted as such by the press.

All this has led to a fierce media (and social media) debate about whether no platforming is limiting free speech. Some opponents have been very vocal. The online magazine Spiked even releases an annual report allegedly “rating” UK universities on the basis of their support for free speech on campus. However, as the populist far Right has grown over the past few years, more students are also standing up for the principle of no platforming as part of a wider defence against xenophobia, racism, misogyny, homophobia and transphobia. Their argument is that if hate speech needs to be shut down for the majority of students to feel safe, then so be it.

With the caustic nature of the far Right permeating the mainstream, it is hard to argue against this. And if the OfS does attempt to crack down on so-called snowflake students determined to defend their campuses’ status as tolerant and equal spaces, it will find itself at the centre of a blizzard of protest.

Evan Smith is a visiting adjunct fellow in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, South Australia. He has written widely on the British Left, anti-racist activism and political extremism, and is currently preparing a book on the history of no platforming. He blogs at Hatful of History.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?