What happened in this and last year’s GCSE and A-level grading is not grade inflation. Grade inflation is what happens when exam boards have variable marking quality/consistency, or lower grade boundaries – there were no exams and no exam boards marking papers this year.

Nevertheless, there has been a marked increase in higher grades. Some (or even most) of this can be attributed to the fact that teachers were marking to grade or performance criteria supplied by the exam boards. That meant this year’s grades were entirely criterion-referenced – that is, students were assessed against a standard without reference to the performance of others being assessed.

The national exam series up until 2010 were mainly criterion-referenced, giving rise to accusations of “grade inflation”, not least from universities finding it difficult to select from multiple students holding high grades. From 2010 onwards, the exams regulator, Ofqual, deployed its “comparable outcomes” policy, which introduced some norm-referencing (looking at performance and relative performance) to exam grading, to smooth the impacts of reforms to GCSEs and A levels and to ensure comparability across different exam boards and cohorts.

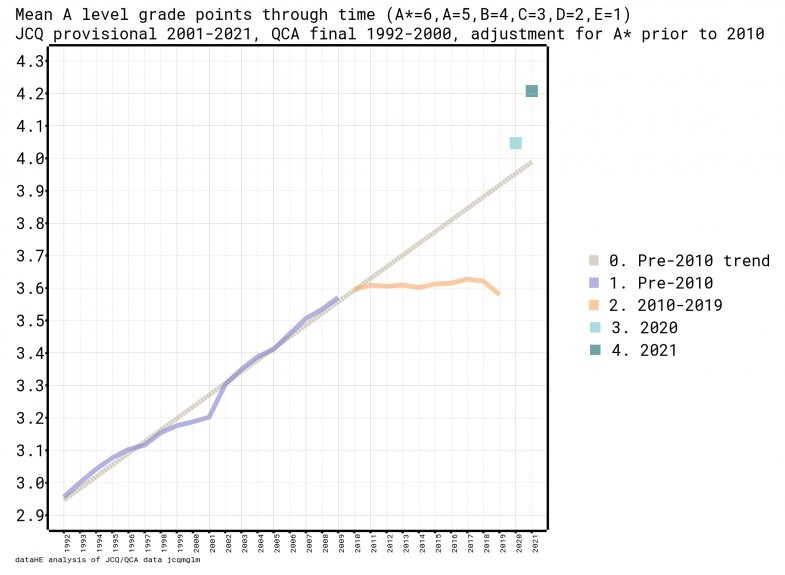

You can see the change of policy quite clearly on this chart from Mark Corver, my former colleague at Ucas and founder of DataHE:

This also plots 2020 and 2021 A-level grade points, showing quite convincingly that these closely match the pre-2010 trajectory. In other words, teachers have probably done quite a good job of matching students against the A-level criteria.

The huge increase in average grades is the result of a combination of non-standard assessment/marking and some optimism bias compensating students for what might have been, but mostly because there was no statistical moderation of the grades. The problems of trying to use an algorithm to do this artificially in 2020 across a non-uniform process are well documented.

The big question is what happens next? The appetite for a return to the familiar single-day snapshot assessments that are exams as we know them is high – public trust and confidence in this method is strong even while educators bemoan the impacts on individuals who might perform badly on the big day, and the exam technique drilling that prepares students for the test.

While a return to exams in summer 2022 seems inevitable, it remains to be seen what smoothing effects will be deployed (and for how many cycles) to combat unfairness between cohorts and to acknowledge the learning lost during the pandemic. Reducing the examined content and increasing visibility of items likely to be tested have been widely mooted. The regulator’s approach to comparable outcomes will be closely watched.

Others have trailed a possible switch to a number grade system for A levels, like the newish 1-9 grades used for GCSEs, but it seems unlikely that this change can be made for the 2022 series given that teachers will need to be predicting grades for their students when the Ucas service opens for university applications in a few weeks’ time.

I first wrote about using a numbering system for A-level grades in Times Higher Education back in 2012. “Is it time to move from A*-E grading to a number-based scale, say 1-10, with 10 the highest? As well as leaving the currency of the current grades intact, this has the advantage of creating a finer scale for selection for competitive higher education courses and a smaller “discount” for near-miss offers,” I wrote back then, anticipating the demographic downturn that would change the supply-demand balance in admissions over the following years.

Now in the wake of the pandemic disruption, a change to the grading taxonomy would provide a reset for the currency of grades without the pain of reforming curriculum and assessment approaches. Ten grades are probably more than needed – GCSEs cover two qualification levels (Level 1 and Level 2) so greater bandwidth is required – and more grades create more grade boundaries around which knife-edge marking decisions can be life-changing for candidates.

On the other hand, universities would welcome finer-grained distinctions, particularly at the top, when a period of demand outstripping supply (and possibly student number caps and minimum entry requirements) will change the selective admissions dynamic.

The more interesting opportunity that a numbered grade system would present is a potential move to single-level tests – in which a candidate could sit an exam for, say, A level Grade 8 mathematics, rather than a paper designed to accommodate a range of grade performances (which is, incidentally, particularly difficult for mathematics).

This approach has been widely used and accepted in music exams. Thinking of assessment as a stepped and when-ready process across the whole 14-19 education phase would be another iteration of this approach, especially if digital tests were available.

I’ve never supported the scrap-GCSEs narrative but allowing students to take grade exams at the appropriate level at 16 if they need this for progression, or to continue their studies and take higher grades at 17 or 18 to support application for higher-level studies makes a lot of sense.

Stage-not-age based education would, admittedly, cause a massive disruption to the organisation of secondary education, but it might support a better, fairer and more motivating experience for students who would be taught with other students at the same level rather than in multilevel classes.

Single-level exams would offer better quality questions, and a more accurate assessment against the standard when even Ofqual admits that current exam marking is only accurate to within one grade either way. Universities might welcome this for admissions purposes.

Discuss, as they say.

Mary Curnock Cook is former chief executive of Ucas.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?