“It doesn’t matter what famous people say. People with knowledge will talk about it.”

Well, thank goodness for German football managers. Jürgen Klopp is undoubtedly a superstar in his field, a charismatic leader of a great Liverpool FC team.

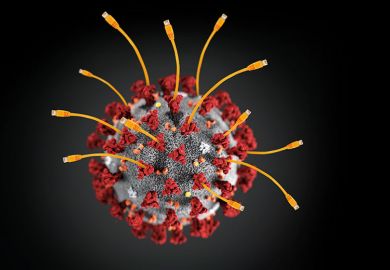

But, as he pointed out when he was asked for his hot take on the coronavirus, he knows no more about public health emergencies than the next person.

And, refreshingly, he wasn’t going to offer layman’s commentary, when what the world needs is to hear from those who know what they are talking about.

It is too early to talk about silver linings or legacies of an unfolding crisis. But it’s abundantly clear that there will be long-term implications, and a reassessment of expertise may be one of them.

When normality crumbles, who do we turn to? The unevidenced claims of newspaper columnists complaining that the “snowflake” generation will be too selfish to self-isolate (as several did last week)? Politicians whose bluffing suddenly loses its appeal? Or those who have devoted their lives to research and its application, and who as a result can help guide us through this global crisis?

There’s no need to answer that one.

Writing in The Times last week, Daniel Finkelstein argued that the coronavirus could prove to be a “9/11 moment” for politics, changing views and policy approaches to almost everything.

Couple it with the climate emergency and it’s not hard to see how a combination of existential threats could shake societies and their ways of doing things to the foundations. Who, for example, will set foot on a cruise ship again?

In all seriousness, there are clear and present dangers – to businesses, certainly, and to individuals’ jobs and families’ homes. There will be implications for global trade, supply lines, and attitudes to international travel, border security and more.

And there will undoubtedly be long-term and very significant implications for universities.

The short-term financial impacts are plain to see. Travel bans, massive hits to revenues from international student fees, cancelled conferences, even the closure of national education systems – universities have been hit earlier and harder than most other sectors.

But the greater disruption may still lie ahead. That is likely to include further operational challenges, certainly. Universities in the UK dealing with the immediate issues will already be looking ahead and wondering how much worse things could be if next year’s admissions processes are significantly disrupted, as they may well be.

And there must be questions in the longer term about higher education’s previously inalienable mantra of internationalisation, internationalisation, internationalisation.

In our cover story this week, we explore how universities in China – which was hit first and hardest by the coronavirus, and contained it with extraordinary measures to lock down the movement of people – have responded.

Bin Yang, provost of Tsinghua University, argues that “in this unforeseen and unpredictable landscape, technology has offered credible solutions to an unprecedented problem. The online tools and upgrades to existing technologies that have been pushed to the forefront of university teaching will emerge as epoch-making platforms in China. They may well establish new global standards, too, and new norms for online and blended education.”

If he is right, the implications of China’s embrace of remote learning will have ramifications for universities across the Western world too.

It is possible that everything will revert to how it was before, but to assume as much would miss an opportunity, as well as ignore a risk.

Although less tangible, another fundamental shift that one could see resulting from the coronavirus is a repositioning of research and expertise in the public mind.

For years now, universities have in an increasing number of countries become targets for those swept up by populist political winds.

Unfair, yes, unwise, certainly, but fiendishly difficult to counteract all the same.

That must now, surely, change. The heroes of the hour are not pundits or politicians, not even German football managers, but epidemiologists and their colleagues. The value of what universities are and do – so often infuriatingly difficult to communicate in a way that sticks – is now obvious to all.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?