As one of life’s incurable optimists, I am upbeat about the prospects for UK higher education. We have one of the best-regarded systems in the world, the quantity and quality of our research output remains formidable, and young people from many countries want to study here.

I am, of course, not naive about the current circumstances and the degree of uncertainty generated by the election campaign. But we should be sceptical when doom-mongers talk about a dark future for our universities.

It is also counterproductive to talk ourselves down. Not only does it lack credibility and judgement, it may simply add to a negative external perception about the UK. Worse, it might mean that universities are not taken seriously as discussions begin in earnest about life outside the European Union.

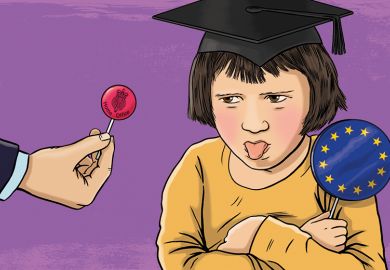

Elections are rarely won or lost on education. However, this campaign has allowed us an opportunity to highlight the success of our universities and, in a measured way, to keep important issues – particularly those relating to Brexit – at the fore. But there is work to do if universities are to maintain their historic position among the most highly regarded of the UK’s national institutions. Even friends like Lord Lucas gently chide us for not always judging the politics correctly (“Acting like spoiled children will do UK universities no favours”, Opinion, 18 May).

We should not sacrifice our deeply held values, such as tolerance, openness to new ideas and commitment to truth, simply because the recent political environment has become tougher for us. Yet to be unbending on everything is to become like the political fundamentalist who refuses to compromise with the electorate.

If, as is predicted, Theresa May returns to Downing Street on 9 June, the sector has ground to make up. Never forget the acidic passage in her speech on immigration to the 2015 Tory conference: “I don’t care what the university lobbyists say: the rules must be enforced. Students, yes; over-stayers, no. And the universities must make this happen.” Ouch.

Furthermore, she has been half-hearted at best on higher education since coming to power last year. In her eyes, universities are a means to the end of national competitiveness, but not agents of change. We must show our mettle and alter that perception.

Even a Labour government is unlikely to be a great friend to universities after the widespread scepticism within the sector about its policy to abolish tuition fees. So how might we proceed in the months ahead? First, we must not convey the slightest sense that we still haven’t got over the EU referendum result. As the election campaign has shown, there is little appetite to rerun the arguments of 2016.

Second, our focus on the Brexit negotiations should be informed by the art of the possible. For every request made, we should recognise that a price might be attached. A deal on continuing access to EU research funding might involve some sacrifice of UK funding. Maintaining a good flow of international students might mean added regulatory demands on individual universities.

Third, we should get behind an outward-looking message that reinforces universities’ trade and soft power benefits. Although some think it trite, there is great value in promulgating a message that the UK continues to welcome talented people. And we should be explicit that international student growth – carefully managed, grounded in data and based on a rational assessment of the country’s future needs – will continue to make a major economic contribution.

Fourth, universities need to marry their global focus with overt activity to support local civic renewal, economic activity and the emerging industrial strategy; interestingly, these themes echo across all the main parties’ election manifestos.

Finally, even where we disagree with them, we need to make policies work. An example might be the proposal for us to sponsor new schools, which the Conservative manifesto appears to revive. If it happens, we should commit to making it a success.

So much of what we do is capable of meeting the great challenges of the moment. We can advocate for – and play our part in creating – a more upbeat and tangible education export strategy as part of the post-Brexit UK’s global trading economy. We are also central to closing the productivity gap in the economy, which is holding us back. We can shape and help to deliver great shifts in social mobility and opportunity through the diverse range of institutions within the sector. Positioned properly, these messages could chime well with the government of the day – and with wider public opinion. No one wants to see our economy weaken or our global influence diminish.

It is all about getting the tone right. This is perhaps a little counter-intuitive for a sector that prizes evidence and analysis, but the fact is that being constructive can be more important, when it comes to currying political favour, than being right. Fairly or unfairly, much of higher education has been seen to offer a Remoaner’s view of the world since last June. Almost a year on from the referendum, we must change the record.

Sir David Bell is vice-chancellor of the University of Reading and was permanent secretary at the Department for Education and Skills and its subsequent incarnations between 2006 and 2012.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?