“You follow drugs, you get drug addicts and drug dealers. But you start to follow the money, and you don’t know where the f*** it’s gonna take you.”

So said Detective Lester Freamon in the trailblazing HBO drama The Wire. Freamon was addressing his young protégés in the Baltimore Police Department, but social scientists would also do well to follow his advice.

The Equality Trust noted in a 2022 report that the number of UK billionaires has grown by 20 per cent since the beginning of the pandemic. Yet it remains the case that, as the geographer Jonathan Beaverstock noted as long ago as 2004, “We have many studies of the poor and an increasing number on the ‘new’ middle classes, [but] there is a dearth of studies focusing on the seriously affluent, and a consequent lack of knowledge about the problems that their success causes for society at large.”

When I did a keyword search recently, the Web of Science returned 1,001,811 publications for “the poor” but just 9,681 for “the wealthy”. “Poverty” produced 107,677 results and “deprivation” 114,268, versus just 693 for “billionaires” and 84 for “plutocracy”. This scholarly preoccupation with subaltern classes, according to Beaverstock, means we end up knowing “more about the poor than the groups who most benefit from [the] global process of capital accumulation”.

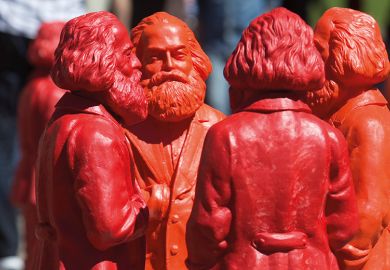

Contemporary researchers are following in the footsteps of classical thinkers from Rousseau to Marx and proto social researchers like Joseph Rowntree. Das Kapital, for instance, is just as much about the conditions of the working poor as about the idle rich bourgeoisie, and this is understandable given that classical sociology was a response to the rise of modern society and its impact on the ordinary masses. But it no longer suffices.

In a 2021 article for the American Journal of Sociology, Daniel Hirschman asks a pointed question: “Why did economists and other social scientists know so much about other forms of income inequality – median incomes, race and gender gaps, returns to a college degree – but so little about top incomes?” So much so that most failed to register the accumulation of wealth by the top 1 per cent.

Hirschman blames what he calls knowledge infrastructures formulated in the mid 20th century. But the failing is not just technical. It is also about the social and political set-up of academic research. For any ambitious scholar with a CV to fill, the poor and working stiffs are more accessible and numerous than the rich. The poor also come in handy for winning competitive research grants. Public funding bodies inevitably reflect government priorities, and ministers have long been obsessed with the poor – in the sense of their being a political burden to be minimised.

To be fair, some good research on wealthy elites has been carried out by urban geographers and sociologists. One popular subject is spatial analysis of wealth in mega-rich cities like London. There’s also a growing body of research around super-rich lifestyles, from migration patterns to fashion and transport preferences. Or for a more psychological approach, there is Boston College’s 2011 survey, funded by the Gates Foundation, into how America’s wealthy think and live (the respondents were a surprisingly dissatisfied bunch).

Few though they are, these studies of wealth offer the beginnings of social science that really matters, prising open the lavish subterranea of the nomadic super-rich. But some scholars in this field argue that even the small amount of research that gets done tends only to gaze at the appearances rather than mine the reality. For instance, the authors of a 2017 study of elite real estate in Hong Kong argue that wealth researchers should not just ask “Who are the super-rich?” and “What do they do?” but also “What made the super-rich and why?”

One researcher to have done this with stunning results is the French economist Thomas Piketty. In his groundbreaking book, Capital in the 21st Century, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, Piketty not only established overwhelming historical evidence for the growing concentration of wealth but, crucially, also demonstrated the re-emergence of patrimonial capitalism: that is, capitalism driven by inherited wealth. In such a scenario, Piketty says, “the past devours the future”.

According to the Nobel prizewinning economist Paul Krugman, Piketty singlehandedly revolutionised economics. And only four years after Capital was published, a group of leading economists and social scientists published After Piketty: a book of essays exploring how his project could be taken forward.

One way is with better data. The Financial Times, for instance, said that some of Piketty’s numbers “appear simply to be constructed out of thin air”. And although Piketty stands by his conclusions, he acknowledges that the data he relied on (some of it plucked from The Sunday Times Rich List and the Forbes Annual World’s Billionaires List) is far from exhaustive or without limitations. That, for him, is part of the problem: governments and statistical agencies are unable to keep up with the globalisation of capital, making it easy to hide super-wealth from scrutiny in tax havens.

But this only makes it even more important for researchers to try harder to follow the money. Failure to do so may still result in mildly interesting and sometimes even socially relevant research that gets you a promotion in academia – but it would have Detective Freamon thinking about confiscating your badge.

Michael Marinetto is a reader in management at Cardiff University.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?