Youth need not be a disadvantage in a dynamic higher education scene, discovers Phil Baty.

“Having an impact on the world is not about tradition and history – it’s about relevance in the contemporary world,” argues Anthony Forster, vice-chancellor of the University of Essex.

Essex, a British institution celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, has climbed seven places to 22nd in the Times Higher Education 100 Under 50 2014. It was founded, says Forster, “as a university for a modern age”. While it competes on the global stage with rivals that have had centuries to accumulate prestige and wealth, Essex believes that its relative youth is a distinct advantage.

“Unhampered by the burden of tradition and history, our focus has always resolutely been on the future,” adds Forster.

The university made an impact on the world very quickly. In 1986, six of its departments were judged to be outstanding by the UK research assessment exercise. Today, its social sciences provision is regarded as among the best in the country. Last year Essex was awarded a prestigious Regius professorship – an academic honour bestowed by the Crown that is so rare that only 14 have been created in the past century (Essex has the only one in political science). The institution also enjoys some of the highest satisfaction results recorded by the UK’s National Student Survey.

“We have always been nonconformist, more daring and more willing to experiment,” says Forster. “We embrace rather than shy away from engagement in controversial issues and encourage members of our community to be tenacious, to question the status quo and to test conventional wisdom. Challenging conventions is in our DNA.”

This risk-taking approach to teaching and research characterises many institutions featured in the 100 Under 50. While the list was conceived as a way to identify the potential stars often crowded out of the traditional global rankings by older, richer, more networked and more prestigious rivals, many of the world’s leading young universities share Essex’s view that youth need not be a disadvantage in a dynamic higher education scene.

Alvaro Penteado Crósta, vice-rector of Brazil’s State University of Campinas, South America’s only representative in the rankings, offers a lengthy list of areas where he believes younger institutions such as his have the edge over their older rivals: for starters, the former can more successfully maintain “a robust synergy between teaching and research”; they are also more able to introduce innovations in their curricula, “sometimes mixing traditional and innovative teaching methods…in ways that older institutions may find difficult to implement”.

From Crósta’s South American perspective, young institutions also tend to be better at identifying real-world applications for their research and generally “offer more flexible mechanisms for interacting with society, including the public, private and third sectors. They are also more responsive to changing demands.”

Paul Wellings, vice-chancellor of Australia’s University of Wollongong (33rd in the table), says: “While we rightly celebrate the achievements and traditions of our ancient universities, we should not lose sight of the fact that most universities have had autonomy and degree-awarding powers for a relatively short period.

“As the THE 100 Under 50 illustrates, some of these have secured global recognition.”

So what has allowed this precocious breed to flourish? For Wellings, former vice-chancellor of the UK’s top young institution, Lancaster University (10th), an essential ingredient is an excellent – and loyal – workforce.

“First, the staff need to be signed up to the institution’s strategy and priorities, rather than being fixed on disciplinary loyalties,” says Wellings. “Second, successful new universities have to demonstrate outstanding attraction and retention policies and practices. The best staff live in a ‘seller’s market’. They need to be certain that spending part of their career at a newish university in the process of building its reputation is both invigorating and a good use of their intellectual powers.”

Flexible and dynamic infrastructure is also essential, he believes.

“Some ancient universities have large and historic estates. These can be a double-edged sword,” he says. “On one hand they sustain reputation through the presence of significant buildings, beautiful collections and important laboratories. On the other, these are a burden as they are expensive to maintain, are often unsuitable for contemporary use and can create restrictions on the mobility of the university’s capital for new uses.

“In contrast, new universities can have greater flexibility and be more responsive to regional economic circumstances and national imperatives.”

Wollongong, up 10 places in this year’s rankings, has been particularly successful in leveraging major infrastructure funding under national competition, Wellings points out.

“To be successful, universities must have a clear mechanism to identify priorities and research strengths, and to position them in the context of national priorities and competitive funding streams. This approach can have a marked effect on the fabric of the institution,” he says.

Since 2008, Wollongong has created an international centre for infrastructure research, a major regional health and medical institute focused on translational work, an institute to explore innovative new materials, a facility dedicated to sustainable buildings and a social sciences precinct focused on early years education.

“The alignment of coherent national policies, supportive local government and ambitious institutional strategy can transform a university and its research capacity,” Wellings says.

“The relative rise in the standing of universities in, for example, Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea shows the power of this approach.”

The success of these areas is starkly illustrated in the 100 Under 50 2014, where all three feature in the world’s top five.

South Korea’s Pohang University of Science and Technology, founded in 1986, takes first place, as it has done every year since the 100 Under 50 was launched. Its domestic peer, the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (established in 1971), is in third position.

Sandwiched between the two South Korean institutions is Switzerland’s École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. In fourth is the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (1991), with fifth spot taken by Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (1991), which has risen from eighth last year and 16th in 2012.

Way Kuo is president of the City University of Hong Kong, joint 17th in the rankings. His six years in office at the 30-year-old institution have been characterised by the sort of “ambitious institutional strategy” Wellings refers to.

“As a young university, we do not have the heritage and pedigree of our sister institutions in other parts of the world,” he says. “This means we cannot rest on our past laurels. But we are also relatively unencumbered by outdated modes of operation and free from being trapped by the burdens of tradition.”

CityU’s mission is to become the “leading professional school in the region and the world” – with a clear focus on applied knowledge, Kuo says.

“I have worked closely with my colleagues to focus on modernising the management, reforming the curriculum, internationalising the campus and enhancing the reward system to unleash the energy and talent of our staff and students to strive for excellence,” he says.

Kuo lists a series of key initiatives.

He says: “We implemented the pioneering ‘Discovery-enriched Curriculum’ to build a strong link between learning and research, nurturing students’ innovation and entrepreneurship. We set up an outreach policy to recruit faculty and students from all over the world to create an exciting multicultural campus environment for teaching and learning. We adopted a performance-based pay review scheme to reward and promote excellence. And we have adopted a forward-looking management philosophy to support diversity and teamwork as the roots of our dynamism.”

The 100 Under 50 is characterised by diversity. As was the case last year, eight nations are represented in the top 10 (compared with just two, the US and the UK, in the World University Rankings).

While the top five is dominated by East Asia, the remainder of the top 10 is a more Western affair: Maastricht University in the Netherlands holds sixth spot and the US’ University of California, Irvine is seventh (down from fifth in 2013). France takes the next two places, with Université Paris-Sud in eighth (up from 10th) and Université Pierre et Marie Curie holding on to ninth. The final top 10 place is filled by Lancaster (celebrating its 50th anniversary this year), which moves up from 14th.

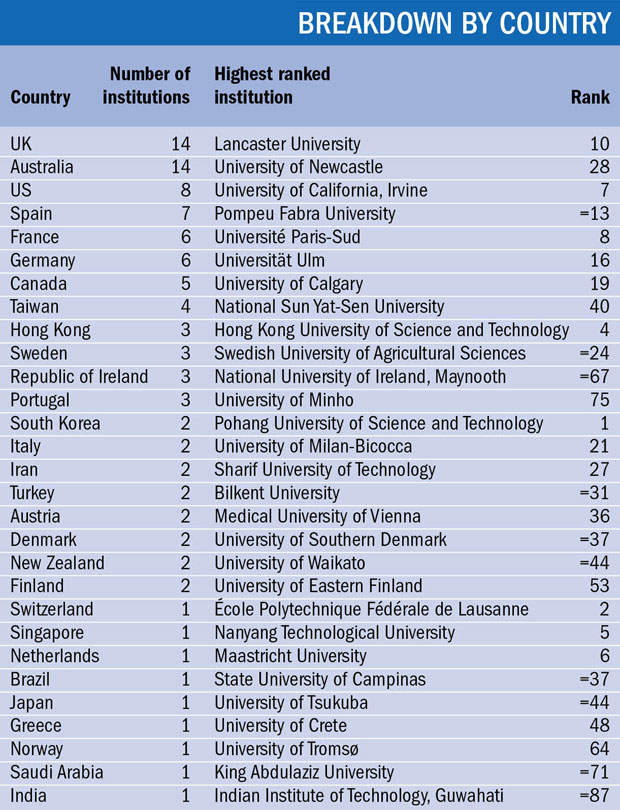

In total, there are 29 nations represented in the 100 Under 50 – one more than last year, as India gains a foothold with the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati (joint 87th). Founded in 1994, it is one of the youngest institutions in the table.

The best represented countries are the UK and Australia (14 institutions each).

The UK’s tally has fallen to 14 from 18 last year (and 20 in 2012) largely because a number of its leading young institutions were founded in 1962 and 1963 and therefore are no longer eligible for inclusion.

This year, the University of York (seventh in 2013) and the University of East Anglia (16th) have dropped out because of their age.

The UK’s representation in the rankings will decline dramatically in the near future for the same reason: the country’s number one in 2014, Lancaster, celebrates its 50th birthday this year. Two other institutions founded in 1964, Essex and the University of Strathclyde (78th), will also exit the tables in 2015 because of their age.

Indeed, only two of the UK’s 14 top 100 institutions were founded after the 1960s – and both are on the up. The duo, Plymouth University (rising from 53rd to joint 42nd) and the University of Hertfordshire (up 15 places to joint 60th), are so-called “post-1992 institutions”, which were allowed to convert from polytechnics into universities after the Further and Higher Education Act 1992 became law.

Australia’s 14 representatives are much more diverse than the UK’s in terms of age: for example, its top three were established in different decades.

The country’s highest-ranked institution is the University of Newcastle, founded in 1965, which occupies 28th place in the table (up from joint 40th). Second is the Queensland University of Technology (joint 31st), which was established in 1989. Third place is taken by Wollongong (founded in 1975).

While time’s winged chariot hurries near for a large number of UK representatives in the 100 Under 50, many of Australia’s more youthful institutions are secure for the time being.

For example, the University of Western Sydney, founded in 1989, enters the top 100 in joint 87th place; Charles Darwin University, also 25 years old, rises from joint 77th to 69th; while the 26-year-old University of Technology, Sydney rockets from 83rd last year to 47th. Age shall not wither their ranking positions for decades.

For Kuo, movement in the tables is a helpful indicator that can inform institutional strategy – but the rankings should not drive it.

“At CityU, we take ranking as one set of important international benchmarks that offer insight into the progress a university is making,” he says. “We are particularly interested in the criteria of different rankings, how these are assessed and the subsequent patterns of results that we can identify. This information enables us to see where we are doing something right and where improvements are called for in order to stay competitive.

“We are mindful that, as with share prices, a university’s ranking can rise and fall. At CityU, we take the long-term view, even though we are a young university. Our goal is long-term, stable growth. That means taking a rational approach to ranking, staying relevant and alert, promoting scholarship and taking responsibility for our future.”

Phil Baty is editor, Times Higher Education rankings.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?