The Times Higher Education World University Rankings are the only global performance tables that judge research-intensive universities across all their core missions: teaching, research, knowledge transfer and international outlook. The BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings use the same 13 carefully calibrated performance indicators to provide the most comprehensive and balanced comparisons, trusted by students, academics, university leaders, industry and even governments – but the weightings are specially recalibrated to reflect the characteristics of emerging economy universities.

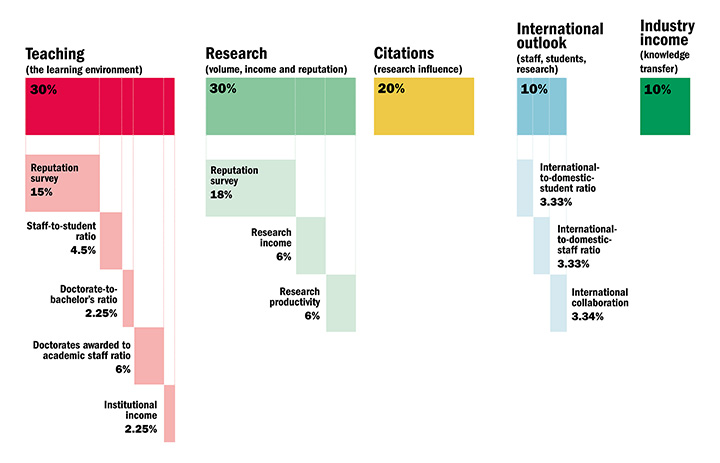

The performance indicators are grouped into five areas:

- Teaching (the learning environment)

- Research (volume, income and reputation)

- Citations (research influence)

- International outlook (staff, students and research)

- Industry income (knowledge transfer)

Exclusions

Universities are excluded from the BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings if they do not teach undergraduates or if their research output amounted to fewer than 1,000 publications between 2011 and 2015 (and a minimum of 150 a year). Universities can also be excluded if 80 per cent or more of their activity is exclusively in one of our eight subject areas.

Data collection

Institutions provide and sign off their institutional data for use in the rankings. On the rare occasions when a particular data point is not provided – which affects only low-weighted indicators such as industrial income – we enter a low estimate between the average value of the indicators and the lowest value reported: the 25th percentile of the other indicators. By doing this, we avoid penalising an institution too harshly with a “zero” value for data that it overlooks or does not provide, but we do not reward it for withholding them.

Getting to the final result

Moving from a series of specific data points to indicators, and finally to a total score for an institution, requires us to match values that represent fundamentally different data. To do this we use a standardisation approach for each indicator, and then combine the indicators in the proportions indicated to the right.

The standardisation approach we use is based on the distribution of data within a particular indicator, where we calculate a cumulative probability function, and evaluate where a particular institution’s indicator sits within that function.

For all indicators except for the Academic Reputation Survey we calculate the cumulative probability function using a version of Z-scoring. The distribution of the data in the Academic Reputation Survey requires us to add an exponential component.

Teaching (the learning environment): 30%

- Reputation survey: 15%

- Staff-to-student ratio: 4.5%

- Doctorate-to-bachelor’s ratio: 2.25%

- Doctorates awarded to academic staff ratio: 6%

- Institutional income: 2.25%

The most recent Academic Reputation Survey (run annually) that underpins this category was carried out in January to March 2016. It examined the perceived prestige of institutions in teaching. The responses were statistically representative of the global academy’s geographical and subject mix. The 2016 data are combined with the results of the 2015 survey, giving more than 20,000 responses.

As well as giving a sense of how committed an institution is to nurturing the next generation of academics, a high proportion of postgraduate research students also suggests the provision of teaching at the highest level that is thus attractive to graduates and effective at developing them. This indicator is normalised to take account of a university’s unique subject mix, reflecting that the volume of doctoral awards varies by discipline.

Institutional income is scaled against academic staff numbers and normalised for purchasing-power parity. It indicates an institution’s general status and gives a broad sense of the infrastructure and facilities available to students and staff.

Research (volume, income and reputation): 30%

- Reputation survey: 18%

- Research income: 6%

- Research productivity: 6%

The most prominent indicator in this category looks at a university’s reputation for research excellence among its peers, based on the responses to our annual Academic Reputation Survey (see above).

Research income is scaled against academic staff numbers and adjusted for purchasing-power parity (PPP). This is a controversial indicator because it can be influenced by national policy and economic circumstances. But income is crucial to the development of world-class research, and because much of it is subject to competition and judged by peer review, our experts suggested that it was a valid measure. This indicator is fully normalised to take account of each university’s distinct subject profile, reflecting the fact that research grants in science subjects are often bigger than those awarded for the highest-quality social science, arts and humanities research.

To measure productivity we count the volume of scholarly output including articles, reviews, conference proceedings, books and book chapters indexed by Elsevier’s Scopus database per scholar, scaled for institutional size and normalised for subject. This gives a sense of the university’s ability to get papers published in quality peer-reviewed journals.

Citations (research influence): 20%

Our research influence indicator looks at universities’ role in spreading new knowledge and ideas.

We examine research influence by capturing the number of times a university’s published work is cited by scholars globally. This year, our bibliometric data supplier Elsevier examined more than 56 million citations to 11.9 million journal articles, conference proceedings and books and book chapters published over five years. The data include the 23,000 academic journals indexed by Elsevier’s Scopus database and all indexed publications between 2011 and 2015. Citations to these publications made in the six years from 2011 to 2016 are also collected.

The citations help to show us how much each university is contributing to the sum of human knowledge: they tell us whose research has stood out, has been picked up and built on by other scholars and, most importantly, has been shared around the global scholarly community to expand the boundaries of our understanding, irrespective of discipline.

The data are normalised to reflect variations in citation volume between different subject areas. This means that institutions with high levels of research activity in subjects with traditionally high citation counts do not gain an unfair advantage.

We have blended equal measures of a country-adjusted and non-country-adjusted raw measure of citations scores.

In 2015-16, we excluded papers with more than 1,000 authors because they were having a disproportionate impact on the citation scores of a small number of universities. This year, we have designed a method for reincorporating these papers. Working with Elsevier, we have developed a new fractional counting approach that ensures that all universities where academics are authors of these papers will receive at least 5 per cent of the value of the paper, and where those that provide the most contributors to the paper receive a proportionately larger contribution.

International outlook (staff, students, research): 10%

- International-to-domestic-student ratio: 3.33%

- International-to-domestic-staff ratio: 3.33%

- International collaboration: 3.34%

The ability of a university to attract undergraduates, postgraduates and faculty from all over the planet is key to its success on the world stage.

In the third international indicator, we calculate the proportion of a university’s total research publications that have at least one international co-author and reward higher volumes. This indicator is normalised to account for a university’s subject mix and uses the same five-year window as the “Citations: research influence” category.

Industry income (knowledge transfer): 10%

A university’s ability to help industry with innovations, inventions and consultancy has become a core mission of the contemporary global academy. This category seeks to capture such knowledge-transfer activity by looking at how much research income an institution earns from industry (adjusted for PPP), scaled against the number of academic staff it employs.

The category suggests the extent to which businesses are willing to pay for research and a university’s ability to attract funding in the commercial marketplace – useful indicators of institutional quality.

Countries eligible for the BRICS and Emerging Economies ranking:

Country eligibility is determined by FTSE classification.

Advanced emerging: Brazil, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey

Secondary emerging: Chile, China, Colombia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Qatar, Russia, UAE

Frontier: Bahrain, Bangladesh, Botswana, Bulgaria, Cote d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Ghana, Jordan, Kenya, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malta, Mauritius, Morocco, Nigeria, Oman, Palestine, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Vietnam

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?