How are US and UK university systems different?

The UK and US higher education systems are very different from each other, and it’s important to make these clear to students considering applying to both

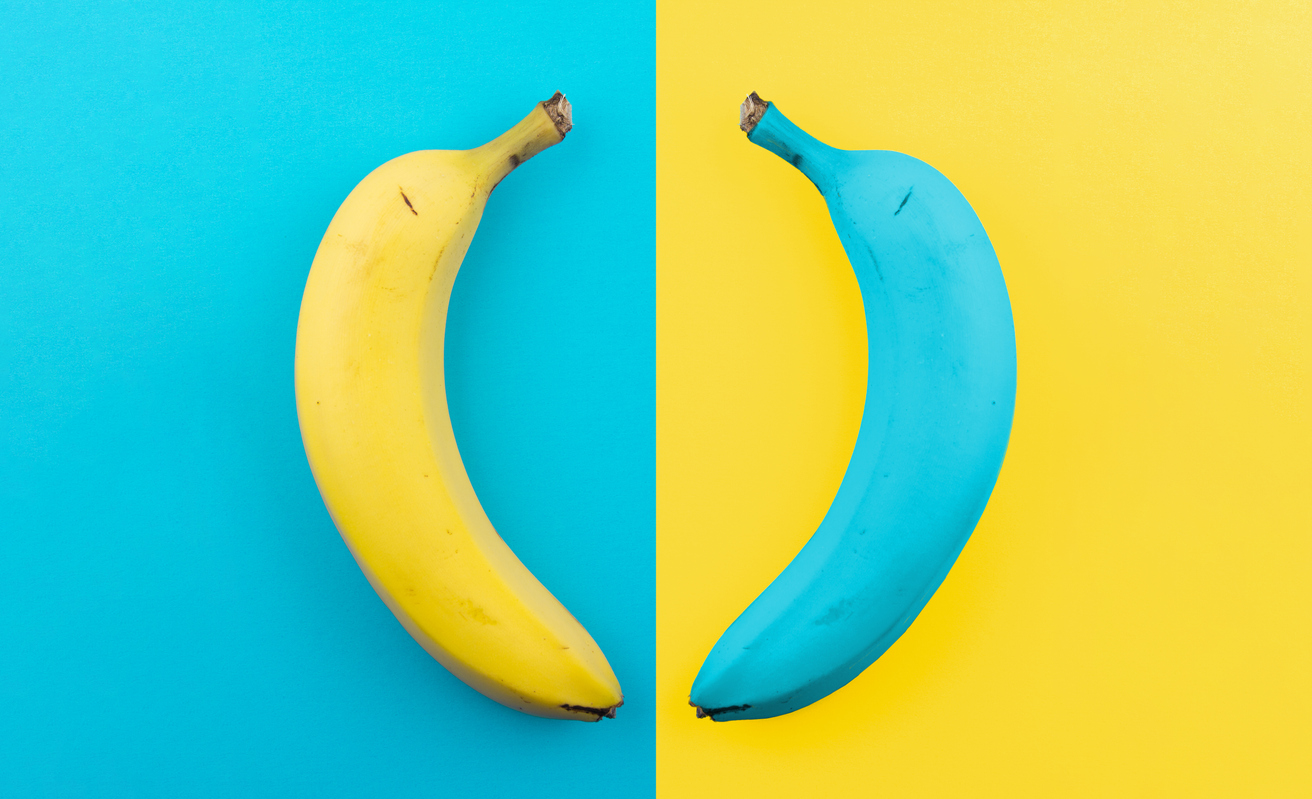

| ˈaɪ laɪk təˈmeɪˌtoʊ, ju laɪk təˈmɑːtəʊ |

Unless you are an amateur linguist and phonemics buff like me, the phonetic symbols above probably mean very little to you. But they highlight American and British English pronunciation differences in all their glory.

I like to quip, echoing George Bernard Shaw’s witticism, that Britain and America are two nations divided not just by their common language but by their utterly distinct higher education cultures. Indeed, this divergence is so pronounced that one might jest they’re the academic equivalent of tea versus coffee: each has its aficionados, and never the twain shall meet without a bit of a stir.

The symbols above read “I like tomato, you like tomato”, by the way. The former pronounced in the American way and the latter correctly.

Student experience: a transatlantic divergence

The student experience in the UK and the US reflects the broader educational ethos of each country.

In Britain, the university journey is heavily based on self-guided learning. Students often find themselves navigating their academic paths with fewer contact hours, necessitating a profound degree of independence from the outset. This approach cultivates a scholarly environment in which self-motivation and personal initiative are paramount, with the onus on students to delve deeply into their subjects outside the confines of the classroom.

Across the Atlantic, the American university experience is more structured, with a higher volume of contact hours fostering a different form of academic engagement. This system creates a dynamic campus life in which learning extends beyond the academic to encompass a wealth of extracurricular pursuits. American universities excel in crafting an all-encompassing environment that supports not only intellectual growth but also personal development through clubs, societies and sports, making the campus a vibrant community hub.

Another key difference between the two is the way in which students choose their subjects. In the UK, students must apply to a specific subject – such as psychology, history, maths and so on – which they will then study in-depth over the next three to four years. As they continue through their degree, students will have the opportunity to select modules in areas of their subject that they are most interested in, in order to specialise their learning more.

In the US, however, students can apply to a university with no idea of what they want to study. In their first year, they can choose a range of classes, across different faculties, to explore various disciplines and discover what they enjoy the most. In subsequent years, students can then whittle down their class choices to be more targeted and will eventually have to declare a “major” in their second or third year. This will be the subject that they will graduate in.

This means the US allows students a lot more flexibility to explore a range of academic areas and interests, while the UK affords students the opportunity to delve in-depth into a subject of their choice.

This dichotomy extends beyond academic structures, influencing student lifestyles and interactions. UK students might find their schedules more flexible, but also more challenging in terms of time management and self-discipline. By contrast, US students often navigate a more prescriptive timetable, balancing the demands of coursework with an array of extracurricular commitments.

Thus the transition between these systems can be striking, as students adapt not just to different academic expectations, but also to different social and cultural norms.

How many contact hours are there?

The number of contact hours – the time students spend under direct instruction from professors – highlights a significant difference between the UK and the US educational systems.

In the UK, a student might expect between eight and 16 contact hours a week, reflecting the system’s emphasis on independent study. This framework assumes that students will spend considerable time outside the classroom engaging in extensive reading and research to further their knowledge.

Conversely, in the US, students typically experience 12 to 20 hours of contact time each week. This difference is indicative of the American approach to education, which favours a more hands-on, guided learning experience. Here, the structure is designed to keep students consistently engaged with their coursework, through a mix of lectures, discussions and practical sessions, ensuring a steady pace of learning and immediate support from faculty.

This contrast in contact hours not only reflects differing educational philosophies, but also impacts students’ daily lives and study habits. UK students must cultivate a high level of self-discipline to manage their independent study effectively, while their US counterparts are often more tightly scheduled, with a greater portion of their learning directed by faculty. This fundamental difference shapes not just the academic but also the personal development journey of students in each context.

The discipline of learning: self-directed versus structured

The discipline of learning in higher education, particularly the balance between self-directed study and structured instruction, varies markedly between the UK and the US.

The UK higher education system places a strong emphasis on self-directed learning, expecting students to take the initiative in exploring their subjects beyond the classroom.

This approach encourages students to develop critical thinking skills, self-discipline and a deep engagement with their field of study. The expectation is that much of a student’s learning will occur independently, through reading, research and preparation for seminars and exams.

This model promotes a scholarly independence from the outset, preparing students for the rigours of academic and professional life.

By contrast, the US system is characterised by a more structured approach to learning. Students benefit from a higher number of contact hours and a continuous assessment regime that provides regular feedback on their progress.

This structure ensures a more guided learning experience, where students have frequent interactions with faculty and a clearer framework within which to work.

The American approach closely intertwines academic learning with a plethora of extracurricular activities.

The transition between these systems can be challenging for students, requiring an adjustment to new ways of learning and studying. While international high school students going to university in the US might be more familiar with the continuous assessment and the need for regular participation in class discussions, those who elect to go the UK for university must adapt to a greater emphasis on independent study and the consequent need for self-motivation.

Campus life and housing: from halls to dorms

The architectural tapestry and living quarters of universities in the UK and the US further accentuate the distinctiveness of each system’s student experience.

In the UK, university campuses often blend historic and contemporary architecture, reflecting centuries of academic heritage. Student housing typically comes in the form of halls of residence, where freshers (first-year students) live in close-knit communities, fostering a sense of camaraderie and mutual support. In all but very rare cases, students have their own bedrooms.

These accommodations often include catered options, providing students with meals. As students progress in their university journey, many move into shared houses or apartments in the local town or city, marking a rite of passage that encourages greater independence.

US universities are known for their sprawling campuses that serve as self-contained communities, complete with residential halls, dining facilities, recreational centres and sometimes even shopping districts.

First-year students usually reside in dormitories, often in shared bedrooms. Dormitories are central to the American college experience, providing a social atmosphere that encourages students to forge connections and immerse themselves in campus life.

The emphasis on campus facilities and extracurricular engagement in the US reflects a holistic approach to education, where personal development is considered just as important as academic achievement.

The contrast in campus styles and student housing between the UK and the US is emblematic of the broader cultural differences that influence university life. For international students, adapting to these environments is an integral part of the overseas educational experience, offering a window into the values, traditions and social dynamics of their host country.

Sports at college – or should I say ‘university’?

The attitude towards collegiate sports is a vivid illustration of the cultural divide between UK and US universities, akin to the contrast between a leisurely cricket match and an intense American football game.

In the US, collegiate sports occupy a central place in university life, embodying much more than athletic competition. Major sports, especially American football and basketball, command substantial followings, turning university athletes into campus celebrities and games into large-scale events. This fervent support for college sports is underpinned by significant institutional investment, with some student-athletes receiving scholarships that fully cover their education as a reward for their sporting excellence.

By contrast, while sports are indeed a part of university life in the UK, the scale and intensity of engagement are markedly less pronounced. British universities foster a sporting culture that values participation and the social aspects of sports, rather than the competitive fervour and commercial aspects prevalent in the US. Sports societies and teams in the UK offer students opportunities to engage in a range of activities, from traditional sports such as rugby and football to more niche interests. However, these activities rarely attain the spectatorship or the high-profile status seen in American universities.

Pedagogical styles: a diverse palette

The pedagogical styles of UK and US universities showcase a spectrum of approaches to teaching and learning, each system reflecting its unique educational traditions and philosophies.

In the UK, the academic structure leans towards lectures and seminars as the primary modes of instruction.

Lectures provide a broad overview of a topic, while seminars offer a forum for deeper exploration and discussion, often in smaller groups. This arrangement encourages students to prepare thoroughly, promoting an environment where independent thought and critical analysis are paramount.

Tutorials offer personalised attention, allowing for detailed feedback and discussion of students’ work. This method underscores the UK emphasis on developing students’ ability to think independently and engage critically with their subject matter.

In the US, the educational approach is notably more diverse, incorporating not only lectures and seminars but also a wider variety of interactive and practical sessions, such as labs, workshops and studio classes. This diversity reflects the American emphasis on hands-on learning and the application of theory in practical contexts. Such an approach is designed to engage students in a variety of learning environments, catering to different learning styles and fostering a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

The pedagogical styles in both the UK and the US are designed to cultivate different skills and attributes in students. While the UK system emphasises depth of knowledge and independent critical thinking, the US approach encourages a broader engagement with the subject, emphasising practical skills and collaborative learning.

The nomenclature of academia

The terminology used within the academic communities of the UK and the US further illustrates the distinct identities of each educational system.

In the UK, the hierarchy of academic titles begins with “lecturer”, advancing through “senior lecturer” to “reader”, and finally to “professor”, the last denoting the pinnacle of academic achievement and recognition. This progression reflects a career path defined by research output, teaching excellence and contributions to the academic community.

Conversely, the US academic system employs titles such as “assistant professor”, “associate professor” and “professor”. These ranks not only signify different stages of an academic career but also often entail varying responsibilities and expectations in terms of teaching, research and service to the university community.

The title of “professor” in the US, similar to the UK, represents a significant achievement, identifying a senior academic with a distinguished record of scholarship.

This difference in nomenclature is more than just semantic; it reflects the underlying values and traditions of each educational culture. For students and academics crossing the Atlantic, understanding these titles and what they represent can be an important aspect of navigating the academic environment and fostering mutual respect and collaboration.