Study reveals worrying implications of warming Western Antarctic Peninsula waters

Sponsored by

Warming water and receding sea ice in the Western Antarctic Peninsula is changing the plankton community there with potential consequences for climate change, according to research led by scientists from Duke University and Duke Kunshan.

Yajuan Lin, lead author on the five year study

The study found water temperature and sea-ice cover to be the dominant factors affecting the makeup of microscopic sea life in the region, which had declined in species richness and evenness, with those changes leading to less ocean absorption of carbon dioxide, the gas associated with global warming.

“This invisible forest in the ocean sucks up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so changes to it are incredibly important,” said the study’s lead author Yajuan Lin, an assistant professor of biogeochemistry at Duke Kunshan University, in China. “The research suggests that forest may be doing less of this in the Western Antarctic Peninsula.”

Supported by a National Science Foundation grant to Nicolas Cassar, a professor of biogeochemistry at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University and co-corresponding author, the study, which began in 2012, is the longest ever time-series research on DNA-based plankton community structure and continuous carbon export in the Antarctic region.

Wake of ship through sea ice, note the beautiful brown of diatoms (photo by Oscar Schofield)

The research vessel Laurence M. Gould docking in Palmer Station

Over a five year period, Lin, and scientists from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Rutgers University, Columbia University and the British Antarctica Survey made trips to the region to collect samples. Those expeditions were spent primarily aboard a research vessel Laurence M. Gould, with short spells at the US Antarctic base Palmer Station and the British Antarctic Survey base Rothera.

The research team collected DNA samples of microbial sea life, including algae and microzooplankton, as well as employing a mass spectrometer to monitor carbon sequestration levels. Following each trip, researchers spent months at Duke University and at the University of Nantes analysing the samples using high-throughput DNA sequencing technology, which allowed them to measure species numbers, community composition, carbon levels and other features in the samples, despite their microscopic size.

The study focused on the Western Antarctic Peninsula region (photo by Oscar Schofield)

Published by the scientific journal Nature Communications, the results for the first time quantitively link plankton community structure to carbon export potential along the Antarctic continent, said Lin.

The researchers found significant changes in the community of microscopic sea life as some organisms better adapted the to a warmer environment with less ice survived and others perished. This shift may have an impact on climate change, as analysis of the changing community showed a reduction in the amount of carbon dioxide it absorbed from the atmosphere, said Lin

The Western Antarctic Peninsula has been the fastest warming ocean globally, so the findings from there are likely to be a good indicator of what might happen elsewhere as a result of rising water temperatures, she added.

“Our findings suggest that as climate change continues to affect coastal Antarctic regions, there could be substantial declines in plankton biodiversity and biological carbon drawdown, impacting the Southern Ocean’s capacity to mitigate carbon emissions into the atmosphere,” she said.

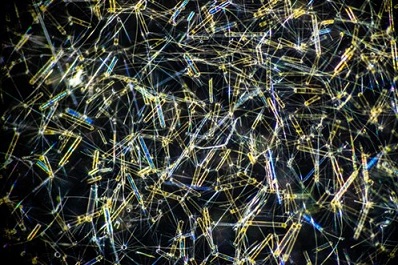

A sample of microscopic sea life (photo by Sharif Mirshak)

The release of Lin’s research findings come in the wake of a statement on the science of climate change published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which detailed the dangers of changes to the world's oceans, ice caps and land in the coming decades. It is also shortly ahead of the 2021 United National Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, scheduled for October, where it could add to debates about both biodiversity conservation and climate change.

“Our results add to the data about climate change and biodiversity, and could help to provide as clearer picture of what’s happening,” she said. “However, a longer study will be needed to confirm the pattern.”