Research for health equity

Research for health equity

By Professor Chloe Orkin, Professor of HIV Medicine, Queen Mary University of London

Queen Mary University of London is at the forefront of medical education and research, with a commitment to achieving better health for all – starting with our diverse community in East London.

The people of East London face many health inequalities. These are unjust and avoidable differences in health across the population and between specific population groups, many of which were identified in The Marmot Review ‘Fair Society, Healthy Lives’[1] and the follow up report from The Health Foundation, ‘Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On’.

The average life expectancy of a woman in Tower Hamlets is 82 years, but her average healthy life expectancy – the years of her life that she will live in good health – is 58. She will spend 24 years of her life with ill health. From Whitechapel, you can take the District Underground line across London to Richmond where the average life expectancy for a woman is 84 years, but she is expected to live a healthy life for 71 years.

Multiple factors contribute to health inequalities and people’s multiple identities such as race, gender, disability, sexual preferences, gender identity, migration status. These can intersect exponentially to affect access to a good education, good housing and clean air. The Lancet [2]has produced an excellent series on how racism and its intergenerational effects lead to worse health outcomes. This exemplifies much of what we have described during COVID-19 in East London where health outcomes were worse in our racially minoritised local communities.

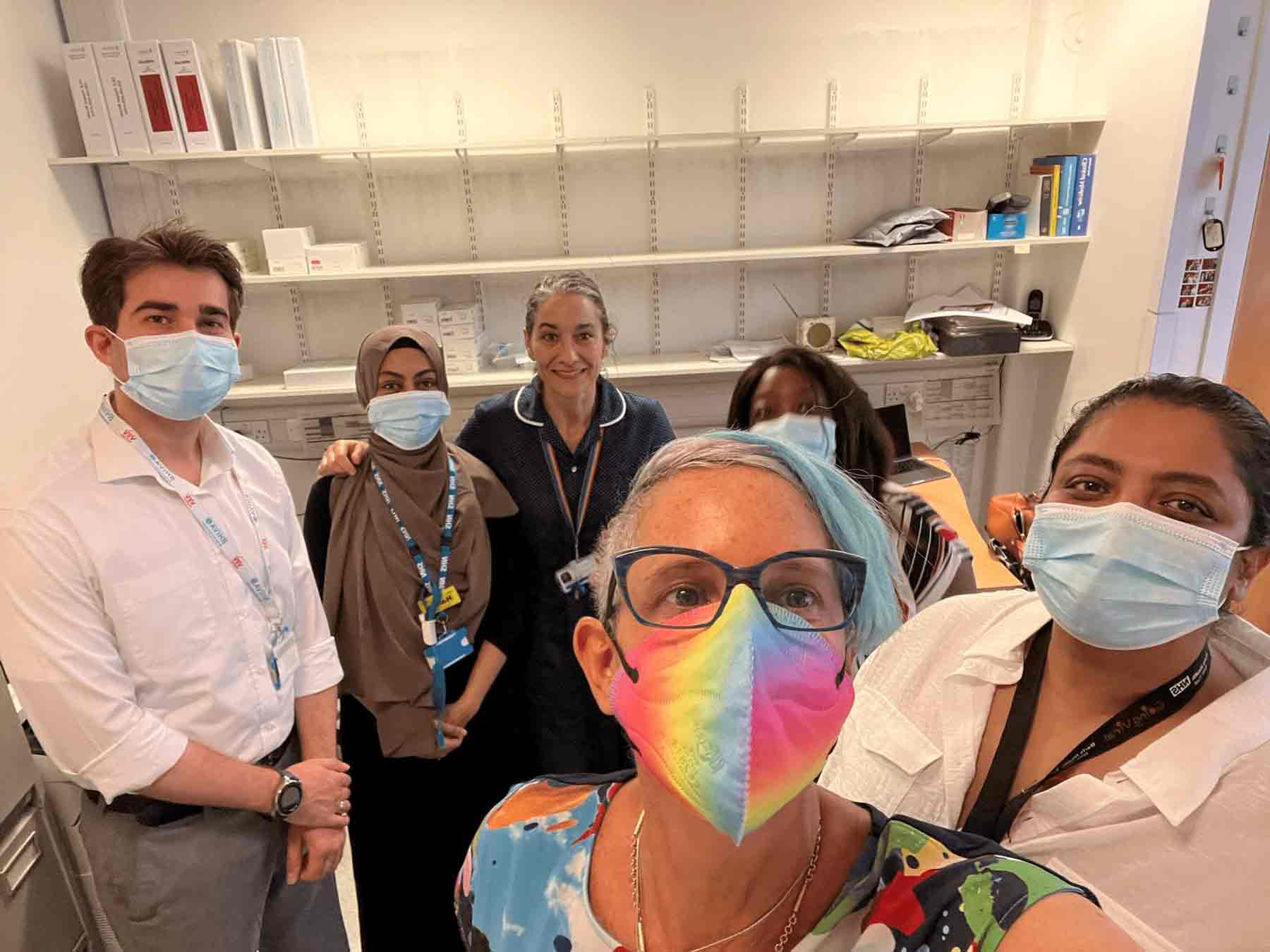

I am Director of the Sexual Health and HIV All East Research (SHARE) Collaborative. The SHARE Collaborative is investigating the inequalities that lead to poor sexual health and HIV. Some of the highest rates of HIV infection and worst HIV outcomes are found in the boroughs of Waltham Forest, Newham and Tower Hamlets. SHARE’s vision is a world where everyone – no matter who you are or where you live – can enjoy excellent sexual health, where new HIV infections are eliminated and in which people with HIV live long and live well.

Understanding MPOX

In May 2022, MPOX (previously known as monkeypox) infection began to affect sexually active men who have sex with men in the UK and in other European countries. As an HIV Physician who has provided care for gay and bisexual men for many years, I wanted to understand more. Although MPOX as a disease has been around for decades, it hasn’t traditionally been considered a sexually acquired infection and has rarely occurred outside Central and West Africa.

So, I contacted international colleagues within my HIV research networks in countries where MPOX had been newly reported. This led to international co-operation between over a hundred collaborating clinicians from 16 countries. Together, we described how MPOX was manifesting and published our findings in the New England Journal of Medicine.

All of the infections were in men and almost all were sexually active men who have sex with men thought to have been infected through close sexual contact. We also found that the virus was behaving differently clinically – most people had far fewer lesions than traditionally described and in different locations. MPOX was almost always affecting the genital skin and was very commonly affecting genital mucous membranes, which is very different to how it has looked in the past.

This study influenced the way that the world thinks about MPOX. Many national and international health organisations, including the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control, changed their clinical definition of MPOX to include the new clinical symptoms that we identified. I was also invited to join the WHO Europe expert clinical group on MPOX.

Targeting interventions

Vaccines and treatments for MPOX were in short supply globally, so it was crucial to target public health interventions to those most at risk during this outbreak - men who have sex with men. Gay and bisexual men represent marginalised communities that have already faced stigmatisation and discrimination, particularly during the HIV pandemic. While good public health identifies and focuses first on the communities at greatest risk, it must be done in a way that doesn’t risk further stigmatisation. This means working with the community to co-develop interventions.

The SHARE Collaborative published the results of a co-produced survey evaluating community perceptions to MPOX public health and media messaging early on in the UK outbreak. We found that even in the communities most at risk there were fundamental misunderstandings of key public health messages like where to go if you’re concerned that you have MPOX, whether to isolate, and the origins of MPOX. There were various important disparities: by educational level and employment in understanding of the information; by ethnicity in trust in healthcare professionals and willingness to accept a vaccine; and by age in decision to engage with healthcare.

By the time we published our first study on MPOX in men, there were already reports of infection in women. However, there were no published reports about these infections. We re-energised the international network to describe how MPOX was affecting women and non-binary individuals in 15 countries. We reported on outcomes in cisgender women, transgender women and non-binary individuals assigned female at birth which enabled us to report on the effects of both sex and gender on health outcomes. The findings were published in The Lancet in November 2022.

Trans and non-binary people are frequently not counted or not included in clinical research, and yet they face some of the most significant health inequalities. We found that transgender women were more likely to be living with HIV and also had higher rates of sexually transmitted infections. As many of the MPOX-related fatalities during the current outbreak have occurred in immunosuppressed people living with HIV, this is an important finding and an exemplar of why disaggregating both sex and gender is important.

I’ve worked as a HIV Physician for decades and have come to understand that biomedical solutions such as vaccines, antibiotics and anti-virals are necessary but not sufficient to solve all health problems. That is why my research focuses on the intersections between structural inequalities and infections like HIV, COVID-19, viral hepatitis and MPOX.

[1] Marmot Review report – 'Fair Society, Healthy Lives, 2010: https://www.local.gov.uk/marmot-review-report-fair-society-healthy-lives and Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On – The Health Foundation, 2020: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on

[2] The Lancet, www.thelancet.com/series/racism-xenophobia-discrimination-health