It is rare that a debate about university teaching makes national headlines. But this past year, Dutch newspapers have printed countless column inches about a subject that touches on national culture, profit, immigration and globalisation: whether too many of the country’s degree courses are in English.

In June, after years of rumbling discontent from critics who felt that universities were chasing international student fees rather than serving their local population, the Association of Universities in the Netherlands put out a plan to cap English-language student numbers to prevent Dutch speakers being squeezed out of dual programmes.

That the issue erupted in the Netherlands is less surprising when you look at the statistics. The country went further than any other European nation in offering higher education in English: three-quarters of master’s programmes at research universities are English-only. The Netherlands also offers 317 English-taught bachelor’s programmes, according to a report last year from Study Portals and the European Association for International Education, English-taught Bachelor’s Programmes – more than any other country except Turkey.

Spain and Germany are not far behind. Each offers more than 200 English bachelor’s programmes, while Denmark and Greece offer more than 150. Continent-wide, numbers have grown more than fiftyfold since 2009 to nearly 3,000 last year, going from “novelty to normal”, as the report puts it, in less than a decade.

Outside the Netherlands, the English question is still more of an academic matter than a front-page debate. But it is beginning to enter political discourse in some countries, and it is unclear if and when further growth could trigger a Dutch-style backlash.

What makes the issue more acute is that national identity and culture are once again key issues in European politics, stirred in part by the arrival of millions of migrants since 2015 and the rise of nationalist parties in practically every corner of the continent.

University leaders are taking notice of the Dutch backlash against English, said Anna-Malin Sandström, a policy officer at the EAIE and a co-author of the report, which drew on anonymous interviews with university leaders. “In international education, people look at each other and learn from each other.”

She said that universities are now no longer offering courses in English simply “because that’s what you’re supposed to do”. Instead, they are being far more “strategic and selective” and “thought through” with their language choices.

Over the border in the northern, Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, universities have taken heed of what has happened in the Netherlands, but still think there is room for sensible growth, said Peter Lievens, vice-rector for international policy at KU Leuven. The country has not taken the same road as its neighbour, he said, which developed “an imbalance that you would not like to have” – with no Dutch courses at bachelor’s level in some areas.

At KU Leuven, just four of 78 bachelor’s courses are taught in English, although many Dutch programmes contain English modules. The feeling in Belgium is that teaching in English should increase, not decrease, Professor Lievens said, although current regulations make that difficult. Teaching in Dutch “limits our international possibilities” in terms of attracting overseas students, he added. “We certainly do not want all higher education to be in English, but a little bit more flexibility would be good.”

In Denmark, meanwhile, the government has said that it would cut between 1,000 and 1,200 English-language places at universities next year because too many international students leave the country after they graduate. A report from the Ministry of Higher Education calculated that only a third of international students made a “positive contribution” to Danish public finances over their lifetime, despite paying between €6,000 (£5,340) and €18,000 a year in fees.

The problem facing universities in smaller countries and regions such as Flanders, the Netherlands and Denmark is that they use a language that is little spoken abroad: international students are unlikely to know the local language to begin with, or to want to learn it to improve their future job prospects. This is one reason that universities have turned to English courses, both for the extra fees international students can bring, and to foster an “international campus” that they hope creates cultural exchange.

The situation is different in Wallonia, a French-speaking region of Belgium where universities can draw on students from the huge francophone world. “You can realise an international classroom easily in French, and this is what our Wallonian colleagues are doing,” Professor Lievens said. “This is an advantage that large language groups have.”

Takeover: global lingo

The same is true for Spanish universities. Spanish university leaders who spoke to Ms Sandström were keen to teach local and international students partly in Spanish and partly in English, giving Spanish native speakers the chance to learn a second global language – English – in a comfortable environment. “What came up in the Spanish countries was that bilingual education was a part of the national strategy,” she explained. “Spanish is already a globally strong language, so perhaps it’s hard to feel a threat to it.”

German lies somewhere between the two: it is not a global language like French or Spanish, but is still far more prevalent – and therefore more useful in the job market – than Dutch or Danish. A sizeable proportion of foreign students in Germany are from eastern Europe and are keen to learn German, said Marijke Wahlers, head of international affairs at the German Rectors’ Conference, so “they would be a bit disappointed if they had to study in English”.

Beyond the impact on students, language policy also has major implications for research academics. If you do not publish in English, “you don’t count” because “no American will ever read a Dutch paper,” Professor Lievens pointed out. It is, therefore, crucial that students in subjects such as biomedical science and engineering – where English is used across borders – have a firm grasp of the language, he added.

Teaching in English also enables universities to recruit from “the biggest pool available” when hiring lecturers, Ms Sandström pointed out.

And yet the fear is that unless there is a German, Dutch or Danish vocabulary for cutting-edge research, these languages will become functionally useless at a high level and will serve only for everyday activities.

“That is certainly an important issue, and we have to be careful not to go too far,” Professor Lievens said. “I think we are all very aware of this risk in the science disciplines, so we will not let it happen, at least not in Flanders.” It would be a danger if all undergraduate courses started in English. “This was where some of the Dutch universities were moving to – and I think probably went a bit too far,” he added.

In Germany, “in the natural sciences it’s very natural to hear everything in English, but less so in the social sciences or humanities”, explained Ms Wahlers. The English-language debate in German universities is “not a discussion about the threat to [national] culture, it’s more about academic language”.

One group in Germany, the Task Force for German as a Research Language, is adamant that “almost everything” in academia should be conducted in German, explained Ms Wahlers. And yet proponents for the use of English are equally vociferous on the other side, she added.

The risk of a backlash against English in universities also depends on whether it is seen as a threat to national language and culture in wider society. In Sweden, there is little sense that English is a danger to Swedish, explained Marita Hilliges, secretary general of the Association of Swedish Higher Education. The country has accepted that “we need English to get by in the world…most children know English by the time they start school”.

The question instead is whether Swedish lecturers are good enough at English to teach in the language, she explained. This was also a concern in the Netherlands, with students complaining of incomprehensible lecturers. Yet, in Sweden, there has been little sign of the intense public debate that has erupted in the Netherlands and Denmark. Even the Swedish Democrats, an anti-immigration party which won 13 per cent of the vote in last month’s election, have not raised the issue, she said.

On the whole, Europe’s new nationalist parties have largely ignored the issue of English in universities. In the Netherlands, arguably the most tenacious campaigners on the issue were not politicians but Better Education Netherlands, a group of lecturers and teachers concerned about teaching quality, who unsuccessfully took two Dutch universities to court.

Only in Germany has a nationalist party taken an interest in English courses, and a passing one at most: the Alternative for Germany, which finished third in last year’s election, said in its manifesto that German should remain the language of teaching and research in universities.

There has also been some discussion about the alleged “parallel societies” of English speakers in German cities: the conservative politician Jens Spahn complained last year that he could not order in German in cafes in some of the trendier parts of Berlin. “It might happen in Berlin, it might happen in Frankfurt,” said Ms Wahlers. But “it’s not a widespread topic” of concern for the German public, she believed.

Attitudes towards international students, national culture and English are so diverse across Europe that trying to predict if and when another Netherlands-style controversy could spring up is difficult, if not impossible. It is not the case that a backlash occurs automatically if English-language courses reach Dutch levels, Ms Sandström pointed out. After all, Switzerland has an even higher proportion of institutions offering bachelor’s degrees in English, but with little negative reaction. “One could assume that it has to do with the fact that it’s a multilingual country,” she speculated.

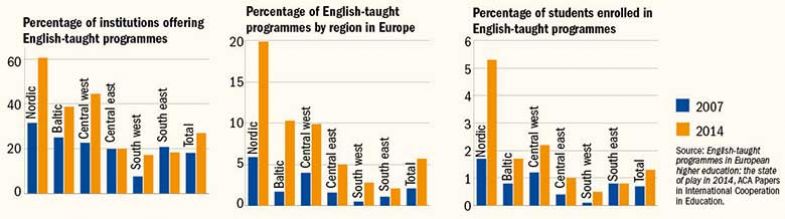

Amid the controversy, it is easy to forget that across most of the continent, only a tiny – if rapidly increasing – fraction of students are taught in English: 1.3 per cent continent-wide, according to one 2014 estimate, rising to 2.2 per cent in Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands, and 5.3 per cent in the Nordic countries.

“The reality is that in some countries, there is enormous room for growth,” Ms Sandström said. Whether growth will happen is “a question of student demand, demand from employers [and] national regulations”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Unease over growth of English-language courses in Europe

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?