With electricity and gas bills soaring, access to Horizon Europe uncertain and tuition fees for domestic students frozen yet again, the £15 billion a year in fee income from international students has never been more important to UK universities.

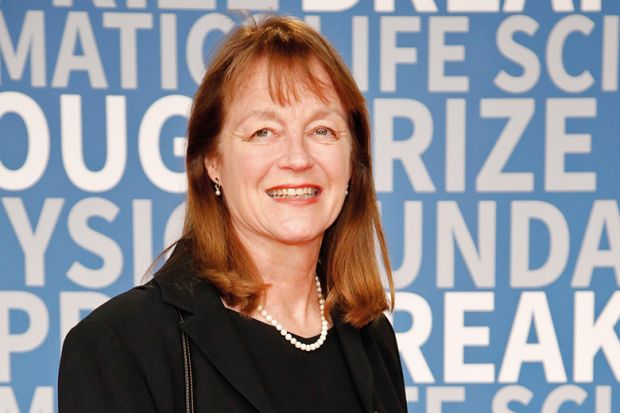

But neither that enormous sum, nor the additional £13 billion a year they spend outside campus, based on Universities UK data, may not be the best argument when it comes to convincing ministers or the public about why international students are so important, believes Alice Gast, who recently stepped down as president of Imperial College London after eight years leading the revered British research powerhouse.

Instead, Gast, a US-born chemical engineer who has taught at Princeton and Stanford universities, as well as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where she was vice-president for research, would prefer to see UK universities highlight the entrepreneurial impact of their foreign students and alumni – in particular, how they create jobs on British soil at scale, often in emerging high-tech industries or in areas in need of economic redevelopment.

“International students don’t just contribute economically during their studies or become brilliant diplomats for British science if they return home – those who stay here will often start companies and create jobs,” explains Gast, now emerita professor of chemistry at Imperial, where she will focus on supporting university spin-out companies and philanthropy.

“These graduates create far more jobs than they consume – maybe we should be expressing this kind of value to the economy rather than talking about the resources which they pay into universities in terms of fees,” she continues.

That contribution is embodied one of Imperial’s student start-ups, Puraffinity, a water-purification company set up in 2015 whose founders included three international students, including its Danish CEO, Henrik Hagemann, and board member Gabriella Santosa, originally from Indonesia.

“It’s gone from winning our innovation prize and using start-up space on our South Kensington campus, then moving to bigger premises on our White City campus,” explains Gast of the company, which won a £1.5 million Innovate UK grant in April, following a £1.2 million Horizon grant and almost £3 million in venture capital funding in 2019. “Now they are building a plant in the north of England, which is exactly how research in London might help the government’s levelling-up agenda,” she adds.

While detailed economic analyses of how international students directly support the UK’s higher education and research system (for every 14 international students studying in the UK, the economy benefits from £1 million in spending, says UUK and Higher Education Policy Institute-commissioned research published in September 2021), these tales of entrepreneurial success might cut through more effectively, insists Gast.

“The fact that most tech companies in Silicon Valley have a founder who was an international student is well known and much celebrated,” she says, with the obvious example being Elon Musk, the maverick South African-born CEO behind PayPal, Tesla and SpaceX who is now the world’s richest man, worth an estimated $277 billion (£226 billion). More pertinently, his companies directly employ 110,000 employees, mainly in the US. “We could do a much better job of celebrating these people who stay and contribute so much to society,” she adds.

That so many overseas-born alumni end up creating companies in emerging technologies is no fluke, either, believes Gast. “To be an entrepreneur, you need to be a risk-taker,” she explains. “But international students are already risk-takers – in that they have come to a completely new country to study – and will often be ready to seize an opportunity when it presents itself. Those personal traits of being open to new things and taking risks are what makes entrepreneurs successful,” Gast continues.

Her impassioned call to recognise the broader value of international students reflects one of the major political battles fought by the sector in the first five years of Gast’s term of office: the campaign to reinstate the two-year post-study work visa, which was finally reinstated in 2020-21, having been scrapped by then home secretary Theresa May in 2012.

That policy win – combined with the news this year that the UK had hit its 600,000 international student target a decade earlier than planned – may suggest things are rosy on the foreign recruitment front. That recruitment may, however, prove difficult to sustain, let alone grow, given that the effects of the pandemic (travel restrictions into and from China continue) and Brexit are still not clear. For instance, about 153,000 students in 2020-21 came from the European Union and mostly paid lower tuition fees in line with domestic students, but future cohorts will be charged the far higher fees paid by those from China, India and other non-EU countries.

But the likely loss of access to Horizon Europe, the EU’s €90 billion (£77 billion) flagship research initiative, and the world-class European PhDs and postdocs attached to the scheme, is also a particular worry for Gast, whose institution has more than 2,000 staff from Europe. “It’s really unfortunate that we are having such problems with association to Horizon Europe,” says Gast, who remarks that the “European Research Council has been really essential for building new relationships and links across borders”.

“Higher education has such an international culture, so it’s important that we keep our doors open and collaborate across borders where we can,” she adds.

Fostering these international links with academia, business and charitable donors has been a major part of Gast’s remit as president since starting at Imperial in 2014. Under the US-style leadership model introduced on her arrival, the former Lehigh University president was asked to lead on external affairs at home and abroad, while the newly created role of provost would deliver the college’s “core academic mission” of research and education.

While Gast has done her fair share of globetrotting in the job, it seems she is equally, if not more, proud of her efforts in expanding Imperial’s engagement with the local community – not perhaps a role traditionally associated with a scientific powerhouse whose main campus is located in South Kensington, one of London’s richest areas.

“I came from Lehigh University, which is found in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania – which was a steel community that made enough for a battleship a day in World War Two, but those jobs have gone,” explains Gast.

“My time at Lehigh showed me what was possible when working with the local community – universities are anchor institutions and cannot be ivory towers, however academically strong they are,” she adds.

That engagement has ranged from opening up Imperial’s plaza to draw in visitors to the many museums in South Kensington to going further afield. Imperial is due to open a new maths school in Finchley, north London, for sixth-formers aged 16 to 19, while it has also partnered with the University of Cumbria to launch a new graduate medical school in the north-west of England, which will open in 2025.

Opening Imperial’s White City campus in west London in 2016 has been particularly important in furthering that engagement, says Gast. “As we moved into a deprived neighbourhood, it was easier to bring schoolchildren into our campus and show them our maker spaces and what we do,” she says, adding: “There was no point in building a new campus where the local community did not feel welcome.”

That activity may seem peripheral to Imperial’s core mission as an elite global university, but it may assist in unseen ways, such as efforts to raise charitable funding, says Gast. Even in the US, where alumni donate to their alma mater more frequently, there is a growing shift from “loyalty based” giving to “impact based” giving, with potential donors more happy to dig deep if they can see how their funds might help specific school outreach projects, university start-ups or research initiatives.

“Donors are becoming much more focused on making sure their gifts have the highest impact and will often want to meet academics in the place where the magic of research happens.”

Imperial’s status as a globally elite science university may make it an unlikely champion of inclusivity, but Gast clearly sees that a spirit of openness – whether it is donors, international students or local schoolchildren – is entirely in sync with the university’s commitment to excellence. In many cases, it may even push it to new heights in unexpected areas.

This is part of our “Talking leadership” series of 50 interviews over 50 weeks with the people running the world’s top universities about how they solve common strategic issues and implement change. Follow the series here.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Embrace ‘risk-takers’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login