After close to a decade of scandals that have felled numerous high-flying German politicians, the war on academic fraud is gradually being won, according to the country’s most high-profile plagiarism hunter.

Since 2011, Martin Heidingsfelder, a former international-level American football player with a passion for sticking to the rules, has helped create several online plagiarism websites that have unearthed fraud after fraud in the theses of Germany’s political class.

Only last month he claimed his latest victim: the Free University of Berlin stripped a conservative MP, Frank Steffel, of his doctorate after an investigation triggered by a tip-off from Mr Heidingsfelder.

This is only the latest scandal in a plagiarism hunting career that has helped bring down the former defence minister, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, once tipped as a future chancellor, and former research minister Annette Schavan – although since these successes, splits have emerged in Germany’s plagiarism hunting community, with bitter spats over who exactly founded the sites that examine doctorates.

The subject of countless newspaper profiles in Germany, Mr Heidingsfelder’s fame has now travelled abroad: last year a Spanish newspaper commissioned him to inspect the doctorate of Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, during a plagiarism scandal that engulfed Spanish politics.

Germany has become notorious for academic fraud scandals at the highest level. But Mr Heidingsfelder now hopes that his work, plus the scrutiny of other plagiarism hunters online, is finally discouraging the wrong sort of people from entering German politics.

Politicians now sometimes even go to him, rather than the other way around: several of Mr Heidingsfelder’s clients have been rising stars themselves, who wanted to privately check their already submitted university theses for anything that could cause a future scandal, he told Times Higher Education.

One such client was “on the way to a big career in politics”, Mr Heidingsfelder recalled, but broke down in tears when told the extent of academic fraud in his thesis, sinking his chance of high office. “It stopped his career,” he said.

In German politics, “you only come forward if you use your elbows”, he said, referring to an excess of competition and ambition among the country’s political class.

“I don’t want that. I want...people with intrinsic motivations,” said Mr Heidingsfelder, who has himself entered party politics, first for the Social Democrats, and then later with the anti-copyright Pirate Party.

Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the country’s president, was in 2013 accused of plagiarism in his doctorate, but was cleared by his alma mater. But Mr Heidingsfelder still fears that there are plagiarists at the very highest levels of the German government.

Some have questioned whether Mr Heidingsfelder’s plagiarism checks are paid for by those seeking revenge against particular politicians. He keeps the identities of his clients secret, but stressed that it was only very seldom, perhaps once or twice a year, that he is commissioned by a politician to investigate a rival. “Fundamentally, I don’t ask my employers why [they want someone investigated],” he explained.

For anyone wanting him to investigate a regional, national or European MP, he offers a discount. “I want political work to be clean – there are so many criminals working there,” he said. He even has a public post box to receive anonymous packages of incriminating documents.

But much of his work is now rather more mundane: students come to him to make sure their work is fraud-free, while academics commission him to see whether their suspicions about a thesis are correct. Less than 10 per cent of his work now involves digging into politicians’ work, he estimated.

Mr Heidingsfelder said that he has no regrets about any of the accusations he has made, even though they have sometimes been costly. He was once heavily fined by a court – his friends had to stump up the cash – after refusing to retract televised accusations of plagiarism against a psychiatrist who was cleared of wrongdoing by his university.

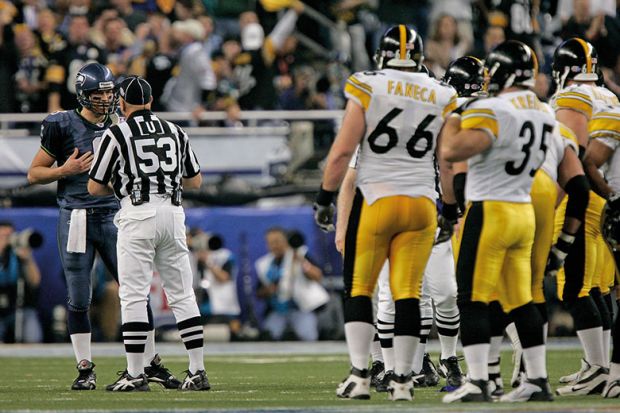

“Looking for justice,” is how he characterises his life principle. As a player for the Ansbach Grizzlies, he learned that “there are clear rules. When you go over the rules, your home team is punished.”

For a three-year stretch during his playing career, recalled Mr Heidingsfelder, he did not commit a single foul, and can still remember the exact infringements (unintentional, he stressed) that broke his clean playing streak.

“It’s my philosophy. Only weak people violate rules,” and they need to be found out, in sport, and in life, he said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?