The site of what was once the Crown and Anchor pub on London’s Strand is now occupied by two chain coffee shops, deserted on a day when train strikes conspired to rid the city of its – already diminished – commuter crowds.

It was here where hundreds of students came together to found the London Mechanics’ Institute – a precursor to Birkbeck, University of London – two centuries ago this year.

Operating on a subscription model whereby students clubbed together to pay lecturers to teach them subjects of their choice, London’s “night university” would later employ or educate some of the 20th century’s most influential thinkers – from activist Marcus Garvey to historian Eric Hobsbawm – while retaining a commitment to offer a high-quality education to those already working or who might otherwise be excluded.

“Birkbeck has always been committed to a much more equal, much more radical educational agenda,” said Joanna Bourke, a professor of history at Birkbeck who has penned a history of the college for its bicentenary year.

“It admitted women in 1830, more than a decade before any other university…there was a radicalism that people have a right and a duty to be educated and of course they faced huge hostility for that.”

The outpouring of concern that greeted news of financial difficulties at Birkbeck last year gave some indication of the esteem in which the institution is held.

In its 2021-22 accounts, the college posted a £9.2 million deficit as income from tuition fees fell and staff expenditure rose. Unions fear up to 140 job losses as departments are restructured.

But the fact the college was suffering did not surprise Jonathan Michie, chair of the Universities Association for Lifelong Learning, who said he was more shocked that it had “managed to struggle on as well as it has”.

Professor Michie, president of Kellogg College, Oxford, has charted how for much of the 21st century the UK’s policy environment has undermined the efforts of specialist providers such as Birkbeck and the UK’s largest academic institution, The Open University, as well as any other university that seeks to offer part-time, flexible or adult education alongside its traditional offering.

“It is frustrating that all the political parties claim to be fully supportive of lifelong learning,” said Professor Michie, former professor of management at Birkbeck. “They all say they recognise it is becoming more important – with new technologies, longer retirement ages, social cohesion, and the idea of ‘building back better’.

“At the last general election, all three parties were very explicit about supporting lifelong learning, but their actions are not just useless, they are actually worse than useless. When they have been in government, all of the parties have damaged the sector.”

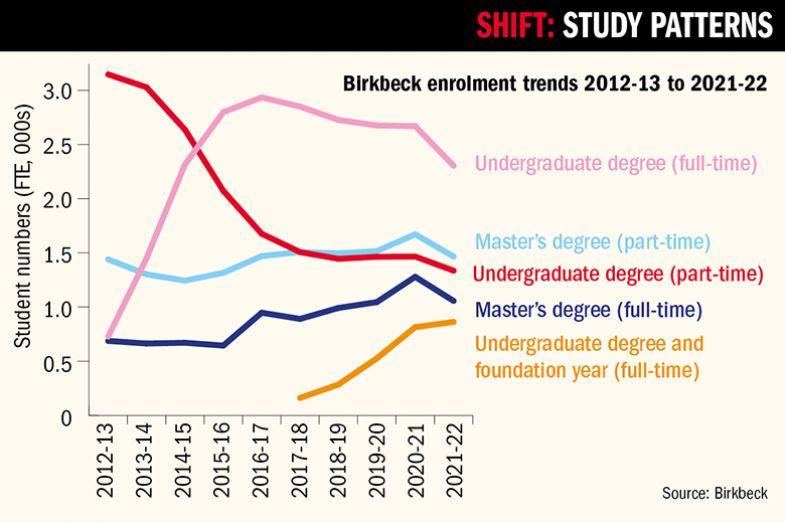

Particularly damaging have been higher tuition fees, the lifting of student number caps, the decade of austerity that has kept wages low and the introduction of the equivalent or lower qualification rule that prevents students obtaining funding for a course if they have already have a qualification at the same level. All these shifts have conspired to make part-time study less attractive: while in 2012-13 the number of students studying for a degree part-time at Birkbeck was 3,146, by 2021-22 this had fallen to 1,336.

Pre-university courses that would once have been a pathway into higher education at institutions such as Birkbeck have similarly suffered from a lack of investment and support. In 2020 the Learning and Work Institute found that adult participation in formal education had fallen to a record low, with 4 million “lost learners” in a decade.

Further problems lie ahead because of the new, more stringent regulations that specify thresholds for completion and progression rates introduced by the Office for Students. The more open-access, flexible models needed by part-time or mature students inevitably lead to more dropouts, Professor Michie said, and he believed the new rules would disincentivise the sector still further.

Matthew Innes, deputy vice-chancellor at Birkbeck, said much of the problem lies in policy being designed by those who only have the traditional model of a school-leaver attending a campus-based university for a three-year degree in mind, with “massive unintended consequences” for institutions that have a more diverse student body.

“If you are not an institution working in that model, you are trying to make your product fit into a policy and funding box that is designed to regulate a different product,” Professor Innes said. “That is the challenge that any institution in the lifelong learning, adult education space is now facing.”

It has long been hoped that moves by the Westminster government to offer individuals lifelong loan entitlements – bringing funding for four years of post-18 education throughout their adult lives – could undo some of the damage that has been done. But many remain unconvinced.

“The principle is great,” said Claire Callender, professor of higher education studies at the UCL Institute of Education and at Birkbeck. “There is a lack of flexibility in the current loan system. For instance, students have to sign up for a full degree programme to receive a loan. Whereas with the lifelong loan entitlement, students will be able to take bite-size modular courses and still get a loan, which may be very attractive for somebody who hasn’t been anywhere near formal education for a long time or hasn’t the time to commit to a full-time course.”

But, she said, there are many details still to be ironed out, including how and when the new loan would need to be repaid, who will be eligible for the loan, and which courses will qualify for funding.

“It is very unclear what the demand is for the lifelong loan entitlement,” she added, explaining that take-up in pilots was lower than anticipated.

While lifelong loans may yet make a difference, Birkbeck and other specialist providers are already having to re-evaluate what they do to survive.

The institution has more than tripled its cohort of full-time undergraduate students since 2013 but numbers peaked at 2,934 in 2017 and have been falling since to a seven-year low of 2,304 in 2022. Numbers enrolled on lucrative master’s courses are similarly now on the decline.

It has also tried expansion and opened a satellite campus in 2013, Birkbeck East, in Stratford, east London, in partnership with the University of East London, in an attempt to reach new audiences in a rapidly regenerating part of the capital.

But the new site struggled to attract students, and those it did wanted to study in Birkbeck’s traditional base of Bloomsbury anyway. The college sold its share of the project to UEL in 2021.

Birkbeck’s five-year strategy that heralded the latest round of cuts also includes a big push into flexible and online learning – an area where it faces stiff competition.

Professor Innes said while the face-to-face evening class model worked in the 20th century, it needed to be reinvented for modern-day realities.

“Working practices were clearly changing before Covid and that has now been accelerated,” he said. “A daily commute and staying on two evenings a week to do evening classes is still attractive for some people but not for everyone.

“We are moving towards a more blended delivery model that has really high-quality resources that you can access at a time or place of your choosing, which is complemented by a brilliant classroom experience.”

Professor Innes argued that the new model would not be a departure from Birkbeck’s traditional mission of catering to people who face barriers to entering higher education.

“To me we are actually restoring Birkbeck’s radical edge by really thinking about the problems people in London and the south-east are facing in the 2020s and 2030s and how we renew and refresh our teaching model in a way that becomes more accessible and more flexible for them. I would argue it goes back to our founding values and rethinking how we deliver them,” he said.

Such changes have been accompanied by significant investment in property by an institution that, unlike its University of London sister institutions, previously only hired spaces in the city. Critics have said this was unnecessary expenditure but Professor Innes said the college could not reach its digital ambitions in hired spaces.

Mike Berlin, associate lecturer in history and president of Birkbeck’s University and College Union branch, said none of the attempts by the institution to reinvent itself so far “had really worked” and he feared they risked diluting the institution’s ethos.

“The college’s explanation for the crisis is to do with external factors beyond its control and I think that is fair to an extent, but there has also been a lack of vision and a failure to adhere to the traditions of why people work at Birkbeck, in that it is a radical institution which focuses on working-class education,” he said.

All agree, however, that the problems at Birkbeck go beyond the college itself and will require broader solutions, including more government support and investment for adult education.

Professor Callender believed that employers also have a key role to play, providing financial support for fees and other incentives such as paid time off work to study, as they did in the past when fees were lower and loans were unavailable.

“Basically, we’ve got to think about how we can make part-time study more attractive and more affordable,” she said. “Definitely replacing loans with grants would help but that is unlikely to happen.”

Providers, too, need to be incentivised on the supply side. “If a university has a choice between getting a guaranteed £9,250 for three years from a full-time student or an unknown amount over what could be a 12-year period from a part-time student, what would the university go for?” Professor Callender asked.

“There are additional costs involved in teaching part-time students, whether that’s because more people are using the library, or having to keep buildings open ‘out of hours’ with more security and the additional energy costs. Part-time study has to be made financially worthwhile for all types of universities and providers.”

Institutions do not survive 200 years without being adaptive and Birkbeck has faced existential crises before, Professor Bourke said.

It weathered the expansion of higher education in the 1960s and cuts to the funding for part-time students in 1986, which caused a “massive reorganisation of the college”.

“What is so striking is [that in] every single crisis we have gone through, it has been students and staff who have fought like hell for the college and have put forward constructive ways of adapting to the educational world that is around us,” she said. “That is what is happening now at Birkbeck and I am optimistic because of that.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How Birkbeck was let down by decades of ‘damaging policy’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?