India appears set to overtake China as Australia’s top education market in a change of the guard with potentially major ramifications for university finances.

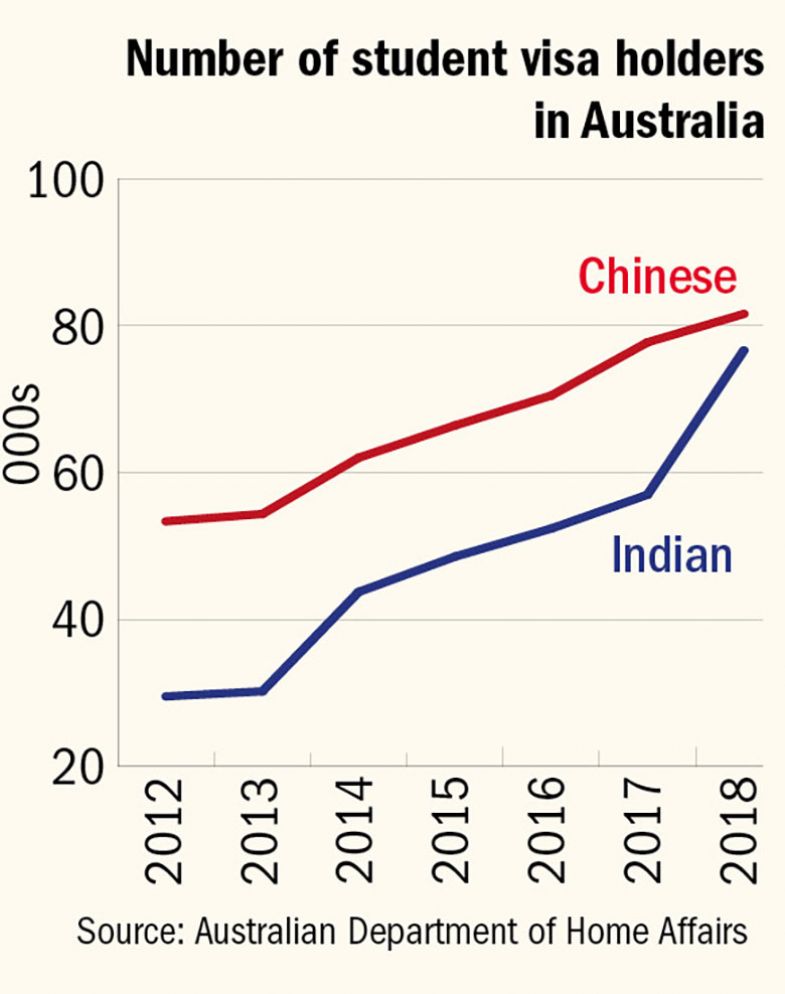

Growth in the number of Indian students in Australia was five times as fast as expansion of Chinese student numbers in 2018, and Australia was home to just 5,000 more Chinese than Indian students by the year’s end – compared with a gap of more than 20,000 in 2017, according to newly released data from Australia’s Department of Home Affairs.

The trend is set to continue, with the department processing 12 per cent more student visa applications from India than from China by the end of 2018 – a turnaround from the year before, when officials were dealing with 26 per cent more Chinese applications.

The pivot to India could hurt the university sector because Indians are about 50 per cent more likely than their Chinese counterparts to pursue vocational study. Some individual Australian universities that already enrol far more Indians than Chinese could benefit.

However, the prestigious research-intensive universities will be disadvantaged because they rely heavily on Chinese students. The University of Sydney and UNSW Sydney both sourced more than 26 per cent of their revenue last year from Chinese students’ fees. Melbourne, Monash, Queensland and the Australian National universities are also highly dependent on this income stream.

On 15 June, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that UNSW had decided to postpone a planned increase in foreign students’ English-language requirements after a fall in the number of first-year international students. UNSW’s vice-chancellor, Ian Jacobs, said the report had been based on an internal “review process” that did not constitute university policy, adding that fluctuations in international student numbers were “normal” but entry standards remained high.

The Home Affairs report shows that Indian student numbers are skyrocketing, with the number of successful visa applications climbing by 54 per cent over the second half of last year compared with the same period of 2017. Meanwhile, Chinese visa approvals declined by 3 per cent – the first such fall since the department began reporting these statistics in 2011.

Rising: Indian visa uptake

An increasing proportion of these Chinese students applied for their visas not from their homeland but from within Australia. The number of these “onshore” visa applicants rose by 14 per cent, helping to offset an 11 per cent drop in new Chinese visa holders who had applied from outside Australia.

This continues a trend in which fresh arrivals constitute a declining proportion of Chinese students in Australia. Experts struggle to explain this phenomenon, with the obvious interpretation – that many students already in Australia are staying on to obtain higher qualifications than they had originally planned – not supported by the data.

The Home Affairs report shows that, across all nationalities, the number of new student visas issued to people with previous student visas fell by 28 per cent. Rather, growth in student visa uptake came from people in Australia on family, visitor and temporary resident visas.

This suggests that an increasing proportion of Chinese students may have originally come to Australia for other purposes. However, the size of this pool is also shrinking.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data show that the number of visitors from China has fallen for 10 consecutive months and is now at its lowest level in two years – a trend consistent with suggestions that Chinese media criticism of Australia, a side-effect of the countries’ tense bilateral relations, is dampening Chinese people’s enthusiasm to travel there.

International education expert Jonathan Chew said the universities most disadvantaged by such trends would be those that had made recent investments to attract more Chinese students, by appointing more staff in China and increasing commissions paid to agents.

“It’s unfortunate timing that you’ve got institutions trying to turn on the tap just as these headwinds are starting to blow,” said Mr Chew, a consultant at Nous Group.

In another potential blow to Australian universities’ coffers, there are signs that some Chinese students ostensibly in Australia to undertake higher education may never do so.

Many Chinese students visit Australia on “packaged” visas that authorise stints of English-language study and possibly short “non-award” courses, culminating in university education. Home Affairs includes them among the 85 per cent of Chinese student visas that are attributed to the higher education sector.

Education department figures from last year suggest that this figure is vastly inflated. Higher education claimed just 49 per cent of new Chinese enrolments, with 27 per cent of commencements in language colleges and 9 per cent in non-award courses – categories that barely register in the visa data.

“It’s highly likely that some of these students on higher education visas never had any intention of becoming higher education students,” said Danny Bielik, a former New South Wales government education adviser who now runs Singapore company Burst Learning.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Indian traffic set to outstrip Chinese en route to Australia

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?