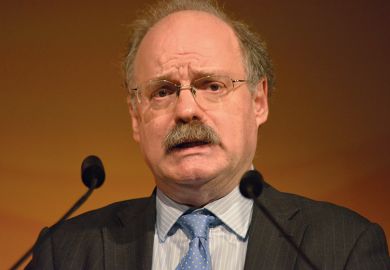

The position of chief executive at the newly created organisation UK Research and Innovation is widely touted as the most powerful job in science in the country.

Earlier this month, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy announced that the role would be filled by Sir Mark Walport, who is currently the government’s chief scientific adviser.

As news of the announcement spread, many academics congratulated him, but others expressed concern, with one researcher reportedly comparing him to Donald Trump. So, who is Sir Mark, and why do some people think that he is a controversial choice to watch over the nation’s £6 billion research budget?

Sir Mark studied medicine at the University of Cambridge and trained in London teaching hospitals before returning to Cambridge’s Medical Research Council Centre to complete a doctorate under Sir Peter Lachmann. In a 2003 interview, Sir Mark said that Sir Peter instilled in him a “rigorous and questioning approach to science”.

After his PhD, he returned to London and worked at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School at Hammersmith Hospital, where he progressed from senior lecturer in rheumatology to professor of medicine, and did a four-year stint as director of research and development at Hammersmith Hospitals Trust.

In an article published in The Lancet in August 2003, Sir Mark is described as “the nemesis” of many junior staff during his time at Hammersmith Hospital.

It says that he was “vaunted and feared” by junior doctors on the morning report – an academic discussion of the cases that arrived overnight – “not simply because of his fearsome intellect, but mainly because he was wholly, patiently, and even dispassionately, reasonable…a junior with stung pride found little to rail against except his braces”.

In 1997, he moved to head up the division of medicine at Imperial College London after the merger of several medical schools with the university. During his time in academia, Sir Mark’s clinical and research interest focused on immunology and the genetics of rheumatic disease. He made key contributions to understanding the role of the “complement” system in lupus, according to the Royal Society.

In 2000, he became one of three new governors of the Wellcome Trust, leaving Imperial three years later to become the director of the organisation. During his time running the world’s largest medical research charity, Sir Mark drove forward the open access agenda, making it obligatory for Wellcome-funded researchers to publish their results in journals that can be accessed for free. Changes to research grants under his tenure were also perceived as concentrating funding on fewer, elite researchers.

Sir Mark was knighted for services to medical science in 2009 and elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 2011. In 2013, he left the Wellcome Trust to move to Whitehall, taking up his current role of chief scientific adviser. At the time, some thought that his bold, decisive and, at times, forceful personality would serve him well in the role.

Many have been complimentary about Sir Mark’s suitability for his new post, saying that he has a great level of experience, expertise and was the obvious choice. But others have concerns: Sir Mark has a reputation for bluster and prickles. What may be most telling, perhaps, is the number of people who are unwilling to talk publicly about their experiences of him.

One senior scientist, who spoke to Times Higher Education on condition of anonymity, said that he can take criticism personally.

“People I know have been shocked by his behaviour on occasion and it seems that he doesn’t necessarily realise how he comes across,” they said. “He has very clear views of what he thinks will work and can appear dismissive of other views.

“People appear to be frightened of him. This is an unhealthy state for the community to be in,” they added.

Of course, the image of a very confident professor who can be impatient with others and does not suffer fools gladly is not out of place in academia. Kieron Flanagan, senior lecturer in science and technology policy at the University of Manchester, said: “The difference is that he is in a uniquely powerful role so it may matter a little more.”

Also raising alarm bells for some is the apparently cosy relationship between Sir Mark and Sir Paul Nurse, head of the Francis Crick Institute and the author of the review that led to the creation of UKRI and the position that Sir Mark now holds. Sir Mark was chief scientific adviser when the Nurse review was commissioned, and the pair worked closely together on the creation of the Crick.

In a recent interview, Sir Mark dismissed these concerns, adding that it was people looking for a conspiracy theory where there was none. But Dr Flanagan said that it is a legitimate question to ask. “Even if it is a conspiracy theory, it could affect his credibility,” he added.

Another potential dent in Sir Mark’s credibility as he moves to UKRI is the 2014 decision to locate the Henry Royce Institute, touted as the UK’s home for advanced materials research and innovation, at the University of Manchester.

Capital spending decisions made at the time that this new £235 million centre was granted funding have come under the scrutiny of the National Audit Office and the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee, for the rigour and transparency of the prioritisation process and the assessment of their financial implications.

The Royce Institute is one of several new national research institutes with high political visibility that was launched during Sir Mark’s tenure as the government’s chief scientific adviser. Others include the Sir Alan Turing Institute and the planned Rosalind Franklin Institute, while it has not escaped attention that it was during Sir Mark’s time at the Wellcome Trust that the organisation donated £120 million to help establish the Crick – another research mega-centre.

Many researchers are anxious that his apparent favour for large, high-profile, and at times politically prominent, research centres may come at a cost for university-based science.

Only time will tell how Sir Mark will fare in his new powerful post. But Sarah Main, director of the Campaign for Science and Engineering, cautions against labelling him and Sir Paul the most powerful men in UK science.

Dr Main insists that they are just two people among a network of powerful figures that includes the leaders of scientific companies, the heads of universities and the presidents of the national academies. “Diversity of views is very important...it is important that our network of powerful figures also represent[s] that diversity,” she said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Sir Mark Walport: who is the UK’s science tsar?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?