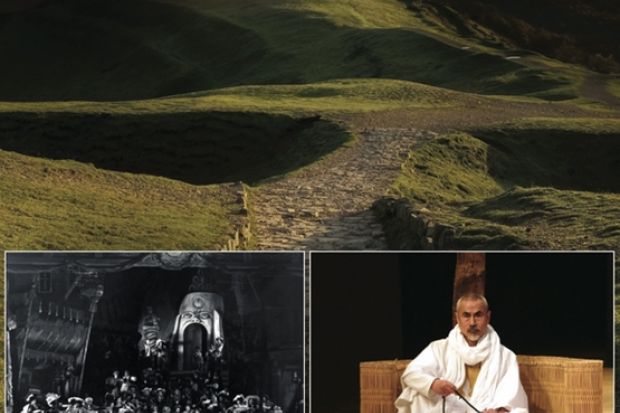

Towards Celestial City: in adapting The Pilgrim’s Progress, Vaughan Williams was alert to its social critique (1951 production, left, current ENO production, right)

The Pilgrim’s Progress

By Ralph Vaughan Williams

English National Opera at the London Coliseum

Six more performances until 28 November

Although comparatively little read today, John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress was, for generations, one of the most influential works in the English language. A new production of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ rarely performed opera of the same name gives us an opportunity to examine how it remains powerfully relevant close to three-and-a-half centuries after it was first published.

Bunyan (1628-88), who was described as a “tinker and a poor man”, is one of the most egalitarian of English writers. Like his account of the Christian Everyman and his journey to the Celestial City, his own confrontation with the iniquitous social, political, legal and economic inequalities of his time - most clearly evidenced by his 12 years spent as a prisoner of conscience under the restored Stuart monarchy - has echoed down through the ages. We can still learn valuable lessons from his resolute opposition to the government of the day and his antipathy towards the emergent unbridled economic system that enhanced an already unjust social structure.

The historian Christopher Hill believed that we are only beginning to catch up with the 17th century. He was well aware that class division or social caste often go hand in hand with injustice of every stripe and knew that Bunyan had much to say about these things. Hill’s acclaimed biography, A Turbulent, Seditious, and Factious People: John Bunyan and His Church, 1628-1688 (1988), traced a multitude of connections between The Pilgrim’s Progress and radical political movements. Some of these resulted in rebellion or outright revolution. The participants in the Boxer Rebellion in China in the twilight of the 19th century and the Russian revolutionaries of the early 20th century are said to have taken inspiration from Bunyan’s text.

Equally deep and widespread, at the other end of the political spectrum, has been the impact of The Pilgrim’s Progress as an evangelising tool by Protestant missionaries in Africa. Of more than 200 translations of the work, 80 are in African languages.

In terms of more strictly literary influence, Bunyan’s impact has been surpassed, among English writers, by only Shakespeare and Milton. William Blake, for example, drew extensively on the apocalyptic and visionary nature of Bunyan’s allegorical works. Commissioned to create a series of sketches based on The Pilgrim’s Progress in the early 19th century, he wrote to a friend that he had “fought through a hell of terrors”, which made it possible to “travel on in the strength of the Lord God, as Poor Pilgrim says”.

Nurtured like Blake in a vibrant dissenting culture, William Hazlitt, too, was an admirer of Bunyan. In his essay “The Letter-Bell” (1831), he eulogises the Shrewsbury countryside, stating that it “stares me in the face…not less visionary and mysterious, than the pictures in the Pilgrim’s Progress”. From a different perspective, Bunyan’s allegory was attractive to those apostates from 1790s radicalism, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey. The last of these edited a landmark edition of The Pilgrim’s Progress in 1830, with an accompanying biography that played down Bunyan the radical and instead emphasised what he saw as his retreat from politics. In Southey’s view, The Pilgrim’s Progress was created despite and not because of the revolutionary times in which Bunyan lived. Just as now, therefore, views of Bunyan from the Romantic period were coloured considerably by politics.

In the US, another great writer on the Puritan past adapted The Pilgrim’s Progress to contemporary conditions. In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Celestial Railroad (1843), the narrator encounters many of the landmarks in Bunyan’s allegory in a scathing satire on the lamentable state of religion in New England and the dominance of unchecked capitalism in 19th-century America.

Yet despite such centuries of global popularity, Bunyan has fallen out of fashion with the general reader. So why should we return to his original text or to Vaughan Williams’ sympathetic operatic treatment of the same story? We might point first to Bunyan’s consistently acute awareness of the socio-economic disparities that have always existed but have seldom been more apparent than now. His insights are especially pertinent in the context of an economic Slough of Despond, a mire from which there appears to be no escape.

In his first published sermon, A Few Sighs from Hell (1658), Bunyan takes as his text the story of the rich man and the poor man, Dives and Lazarus (Luke xvi). This is mentioned again in the House of the Interpreter scene in The Pilgrim’s Progress, where Christian is taught valuable lessons about passion and patience. Things that are temporal are revealed to be transient, and only spiritual wealth is deemed to be eternal. Throughout his life, Bunyan’s writing demonstrates a continuous critical engagement with the economic and spiritual costs of human greed.

Vaughan Williams worked continuously on various aspects of The Pilgrim’s Progress for most of the first half of the 20th century. His opera had its premiere, in its final form, at the Festival of Britain in 1951, and also appeared at the University of Cambridge in 1954, but has rarely been performed since.

On the face of it, Vaughan Williams would seem to have little in common with Bunyan. Born to upper middle-class parents - his mother was a Wedgwood and he was related to the Darwins - he was not even a practising Christian. He was nevertheless committed to egalitarian and democratic ideals and was alert to the kind of social criticism that is everywhere apparent in The Pilgrim’s Progress. In his battle with Apollyon, Pilgrim (as Vaughan Williams renamed the original Christian to further universalise the message) reminds us that the “wages of sin is death” and that his way “is the way of holiness”. It is this holiness and the armour of righteousness that enable Pilgrim to withstand and conquer the seemingly invincible giant. In the Vanity Fair scene that immediately follows, Pilgrim finds himself surrounded by the wages of sin as Madam Wanton offers to sell him “all manner of content”, whether it be flesh or “crowns and kingdoms”.

The world of Bunyan’s Pilgrim, remapped by Vaughan Williams, is not so very different from our own. Given how rapacious the market is represented as being in the original allegory and in the opera, making links with our own historical moment is not hard. Cash for questions in Parliament, corrupt expenses claims from MPs and the fixing of financial markets would have been recognised for what they are in the past as well as now. Everywhere that Pilgrim looks in Vanity Fair he observes greed for money, institutionalised corruption and no access to justice.

English National Opera’s revival of Vaughan Williams’ work is therefore timely. The Chorus of Traders at Vanity Fair sings loudly “Buy! What will ye buy! What will ye buy!” This plea is followed by a list of products and commodities that encourage speculation without restraint. When Pilgrim makes his appearance, the appeal to buy has reached a clamour and he is kettled by the crowd. The chorus comes near to hysteria in urging everybody to buy, and this is echoed by Simon Magus - who offers to sell “the power of God for money”. Pilgrim’s stoic resistance to the spectacle of such blasphemy offers a contemporary audience a salutary lesson in principled opposition to greed sanctioned by legal and government support.

Everything in Vanity Fair, it seems, is for sale, including the law. When Lord Hate-Good makes his appearance and Pilgrim is arraigned before him and condemned as a traitor and a heretic, nobody should be surprised. Pilgrim is inevitably broken by the system.

The Pilgrim’s Progress is clearly a product of its time and steeped in the religious controversies of the 17th century. Yet it is also startlingly modern and open to continuous adaptation. On this score, at least, Christopher Hill was undoubtedly right.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login