Steven Cowley, chief executive of the UK’s Atomic Energy Authority, told the second hearing of the committee’s inquiry into scientific infrastructure on July 2 that the benefits of hosting international facilities “hugely outweigh” the required investment due to their contribution to building skills and their ability to “inspire” both students and academics.

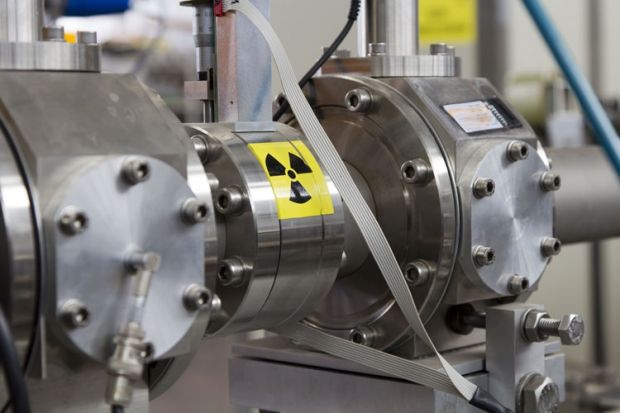

He said the Joint European Torus (JET) nuclear fusion facility in Oxfordshire had attracted €1.5 billion (£1.3 billion) in international investment, of which the UK had contributed just 12.5 per cent.

However, it was the only large UK-hosted European facility. This contrasted with France, which had attracted around half a dozen. This included JET’s successor, known as Iter, for which the UK did not bid.

Andrew Harrison, director of France-based international neutron source the Institut Laue-Langevin, said 80 per cent of the money spent on running his institute flowed back into the French economy. He also noted that of the 37 future projects listed in the EU’s European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructure, only four were UK-led initiatives.

He said one reason was the UK’s particular inability to commit long-term funding to projects. Another problem was the country’s multiplicity of funders and their lack of central coordination over funding priorities.

He said the research councils’ ability to champion projects that were “very distinct and eye-catching” was hampered by their remit to serve “a broad community of interests” of researchers.

“It takes a very brave research council chief executive to say to [universities and science minister] David Willetts: ‘You absolutely have to drive this one forward’ because he then risks alienating big chunks of his community,” he said.

He said the UK’s image as an international partner had declined in recent years, as the country no longer felt it could “afford to be generous”. It has come to be seen as a “standoffish”, “pragmatic” nation that preferred to join international projects only if they were demonstrated to be successful, and was “not very collegiate in terms of getting things off the ground”.

Professor Cowley added that the UK’s lack of central coordination also meant that no one was charged with carrying out the global lobbying required to get international projects off the ground.

He said the demise of the UK’s national laboratories also meant it had relatively few sites with the established expertise in designing, project managing and running large scientific facilities.

He noted that France’s scientific infrastructure was dominated by large bodies such as the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), whose extensive sites were natural homes for large facilities.

“We don’t have those big organisations anymore, and it is less likely that someone in a university group would see [hosting an international facility] as their interest, Professor Cowley said.

He noted that UK science might measure up well internationally in areas of physics and engineering that do not require large facilities, but its declining technical expertise could frustrate attempts to yield economic impact.

“The government is interested in how the science base can really impact on the economy. It can’t do that if no-one can build anything,” he said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login