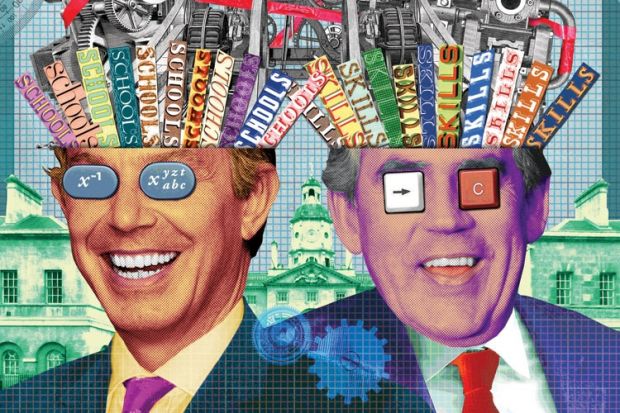

Source: Miles Cole

As one former secretary of state told me, ‘Tony did schools and Gordon did skills…And I don’t think Tony was that interested, I don’t think it fired him’

“Education, Education, Education,” said Tony Blair in 1996 as he famously described New Labour’s top three priorities for government. And then, in the same speech, just a sentence or two later – and rather less memorably – he talked about skills. “Just think of it: Britain, the skills superpower of the world. Why not? Why can’t we do it? Achievement, aspiration fulfilled for all our people. Because a great people equals a Great Britain.”

Like many I thought it was quite a rallying cry, although at the time I did not expect to become quite so closely involved in delivering Blair’s and Gordon Brown’s ambitions. When New Labour was elected I was working in further education, at Waltham Forest College in northeast London. By the time Labour left office in May 2010, I had spent time in a range of thinktanks, as a civil servant in the Department for Education, at the Treasury on the 2006 Leitch Review of Skills and finally as special adviser at the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills.

During this period in Whitehall, I found very little time to reflect on how and why policy was being made – hardly surprising given the breakneck pace of modern government, with round-the-clock demands from ministers, civil servants and the media. But it was also Labour’s interest in making so much skills and education policy that made life so busy.

Two leading academics – Frank Coffield, emeritus professor of education at the Institute of Education, and Ewart Keep, professor of education at the University of Oxford – have described this as “running ever faster down the wrong road” or “running up a dead-end street”. Skills policy suffered not from a lack of attention but rather too much, a pattern Adrian Perry, a principal in further education, has called “policy frenzy”. In my time as a special adviser I worked closely with about 20 different ministers, and oversaw at least 15 white papers and strategies, about 10 independent reviews, the creation of eight new organisations and the closure of seven departments, including two in Whitehall. On top of this, there were the weekly, sometimes daily, responses to the media, ministerial speeches, questions in and from Parliament and briefings, not to mention the odd scandal or crisis.

I decided to try to write up my experiences of policymaking when no longer a part of government. Nearly four years later I’m about to submit my PhD thesis, titled: “Skills and Human Capital under New Labour: what went wrong (and was it my fault)?” At times, this has felt like a distant historical exercise. I interviewed several former ministers, advisers and senior civil servants, and many of us had completely forgotten about policies that we had created. But after chancellor George Osborne’s Autumn Statement and his headline commitment to expanding higher education, it has begun to feel rather more contemporary. Just as I had consigned “mass human capital” to the policy history books, it seems that its time has come around again. Together with the prime minister David Cameron’s talk of a “global race” and the industrial strategy of the universities and science minister David Willetts and business secretary Vince Cable, everything is beginning to sound familiar.

In the mid 1990s, skills policy was emblematic of New Labour. It helped to tell the story of globalisation – of old industries and jobs dying out but with new technologies and skills forming the foundations of a new “knowledge-based economy”. An emerging international consensus formed around this story, shared by Blair, Bill Clinton (US president at the time) and Gerhard Schröder (then German chancellor), and fashioned by the likes of Robert Reich and Anthony Giddens; “beyond left and right”, it offered a “Third Way” between old-style socialism and unfettered capitalism.

As the Leitch Review later set out – and as David Cameron and the education secretary Michael Gove continue to stress – the UK’s skills levels compare very poorly with those of many other countries, including nations in Europe and North America as well as the fast-developing Asian economies. “In the 21st century, our natural resource is our people,” said Lord Leitch’s final report (Prosperity for All in the Global Economy – World Class Skills). Yet, it went on, “in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development comparisons of 30 countries, the UK lies 17th on low skills, 20th on intermediate and 11th on high skills. Seven million adults lack functional numeracy and 5 million lack functional literacy.”

Blair was also more than happy to cede skills policy to Brown. As one former secretary of state told me, “Tony did schools and Gordon did skills…And I don’t think Tony was that interested, I don’t think it fired him, whereas it did fire Gordon. But if you look at what was happening in skills at that time, it was about hands off. It was about self-regulation. It was about the market.”

The Treasury, as well as New Labour, liked “supply side” skills policy because it sat easily with its belief that government should have very little role in markets and in how business worked. The state’s job was to maintain good macro-economic conditions and supply large quantities of skilled people into the labour market. It wasn’t to interfere, or to plan what skills would be needed or how they would be used. That would have been the stuff of “old Labour”, of economic planning, and “anti-business”.

New Labour wanted to build a new global economy and for the UK to lead with a world-class workforce. This marked a shift, as one former secretary of state said to me, from “being on the side of producers to being on the side of the consumers” – a natural consequence of “Clause IV” and the break from 1970s socialism. Labour’s narrative was, according to one of Blair and Brown’s advisers, a kind of British version of neoliberalism created for “partially intellectual reasons, partially political reasons” but ultimately because “we needed a better story”. However, while it was “hands off” in its approach to the economy and to markets, Labour was unashamedly managerialist in its approach to public services and distinctly “hands on” in its approach to delivering skills, introducing an avalanche of policies, quangos, targets and micromanagement.

In opposition, Gordon Brown had set out plans for a skills system led by individual learning accounts and a “University for Industry”. The first would put choice and funding in the hands of learners while the second would transform workforce skills through new technology. Within a few years, however, both had more or less collapsed – learning accounts foundered amid widespread fraud while the University for Industry was found not to be a university at all and not really for industry either. Like so much thinking in opposition politics, both were more slogan than real policy. One adviser who spoke to me, who had worked for Blair, Brown and Peter (now Lord) Mandelson, described the University for Industry as an “empty box”, a “huge, negative legacy” and “a substitute for real thinking”. “It was a classic New Labour thing; it was nebulous. Somehow we were going to use the internet and deliver learning.” Labour had become trapped by its own narrative. The orthodoxies adopted in the mid 1990s to tell “a better story” had restricted its thinking in government. As one former senior Treasury adviser explained, the mantra was that “the economy’s doing well; you don’t pick anything, supply side works. Human capital was safe and it was something that you could tell a really strong story about”. He recalled “the election broadcast that Blair and Brown did when they hated each other’s guts – directed by Anthony Minghella. And he had them talking in some sort of back office and they were going ‘Well yes, it’s all about human capital, responsibility’.”

Ultimately it took the shock waves of a global financial crisis and the disastrous fortunes of Brown’s premiership to free Labour thinking. By 2008-09 few gave Labour much chance of either rescuing the economy or their own prospects in the imminent general election. Much of the skills system was paralysed by bureaucracy and inertia. According to one senior political adviser from the time, skills policy had become a kind of “speak your weight machine”, with politicians robotically reciting data – the system involved huge numbers of learners and vast sums of money but was technocratic and complex and it was difficult to deliver change on the ground. Sir Andrew Foster, in his review of further education of 2005, described a “galaxy of oversight, inspection and accreditation agencies” and a “top heavy” skills system. A former secretary of state described it to me as an “appalling bureaucracy that we’ve inflicted”, “a world in which if you were running an FE college you could barely breathe”.

And the money was running out. The massive investment in rigid, supply-side targets in further education and higher education had to end as the deficit ballooned. “Looking back,” said Mandelson in 2011, “we can see that this approach did neither us nor globalisation itself any favours. It was intellectually abstract and inflexible.” But in Labour’s final two years in power, the start of a period of austerity liberated ministers from the restrictions of their thinking in the 1990s. “Industrial activism”, a term coined by Mandelson and John Denham, saw their respective departments of business and innovation producing a series of more interventionist policies. White papers such as Innovation Nation in 2008 and New Industry, New Jobs in 2009 and a series of sector strategies for manufacturing, life sciences and the creative industries followed. But it was too late to save Labour’s fortunes at the 2010 election.

Today, the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills still leads on industrial strategy as well as overseeing colleges and universities. Brown’s faith in globalisation has given way to Cameron’s talk of a “global race”. The Leitch Review’s comparison of the UK with other OECD countries has been replaced by Gove’s obsession with the comparatively poor performance of the UK in international tests such as the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment and its Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. As Leitch recently put it to me, “Our story of being ‘middle of the pack’ for skills – we were ahead of our time, we talked about a simmering crisis for the developed world and what has happened? Exactly that.”

Then, at the end of last year, and seemingly out of the blue, came Osborne’s Autumn Statement, with the Treasury – so often, under Brown, the author of skills policy – announcing a Robbins-style expansion of about 60,000 higher education places by 2015-16. On current demographic trends that would take the UK well beyond Blair’s 50 per cent target for participation in higher education – one of Labour’s flagship policies for boosting human capital. On top of that, Osborne announced major expansion of apprenticeships – another favoured policy of Brown. Support for science and key industrial sectors and technologies continues, too.

So the Treasury, once described in a journal article by Colin Thain, professor of political science at the University of Birmingham, as “an old-fashioned villain in an Edwardian melodrama – booed whenever it makes an appearance on stage”, has continued to take the lead on skills policy. And with its commitment to expanding higher education, it now sounds more fairy godmother than pantomime villain. The announcement also fit with the Treasury’s view that ultimately the UK’s enduring economic challenge is weak productivity rather than shorter-term recessions or unemployment.

Osborne, like Brown when he was chancellor, knows a good story when he sees one and is equally fond of the political theatre of an Autumn Statement as a place to tell it. Even better if it costs little or nothing and if it sets a political challenge to the opposition. In a period of austerity, the “never-never”, credit-based financing of university expansion looked like one of the few options available.

But Osborne’s announcement represents the same thinking that dominated Labour policies in the 1990s and 2000s. Despite talk of the “eight great technologies” that will propel the UK to future growth, the Treasury is still more comfortable with altering the supply side than with market interventions and industrial policy.

And many will see the move as a sign of the same ineffective and ultimately unaffordable ambitions that Brown’s Treasury harboured prior to 2007. Do the economics or the finance stack up? And did they in 1997, as Labour entered government? The answer to both questions will continue to be keenly contested.

For Osborne, just as it had been for Blair, Brown and Mandelson, the combination of human capital, knowledge and growth have proved a powerful and irresistible story. Importantly for me, that suggests that the reasons why skills policy “went wrong” might not have been my fault after all.

Education, education, education? Perhaps. But what Blair was really demonstrating in 1996 is equally true today: in politics, what really matters is “narrative, narrative, narrative” – and all the better if the Treasury helps you to tell the story.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login