Source: Miles Cole

It has no students, awards no degrees, owns no property. Yet it plays an increasingly important role in the academic life of the nation and the world

As Regius professor of history at the University of Cambridge, I’m caught by the university’s rule that requires professors to retire on the 30 September following their 67th birthday. Mine is on the day before, 29 September 2014, so I’ll have to vacate the office and make way for my successor this year.

But I will not be at a loose end. As well as continuing as president of Wolfson College, Cambridge, I am fortunate that the part-time position of provost of Gresham College, London becomes vacant with the retirement of the present incumbent, my fellow historian Sir Roderick Floud, just as I leave the Regius chair. After a taxing interview with members of the college’s council – would I have the time? (yes); was there a clash of interest with my college headship? (no) – I was offered the post, and accepted with alacrity.

Gresham College is one of British higher education’s oldest and most unusual institutions. Founded in 1597, it has no students, awards no degrees, sets no examinations and owns no property. There are no permanent teaching posts, and there is no set curriculum for its public lectures. Yet it plays an increasingly important role in the academic life of the nation, and indeed, of the global academic community.

The college came into being thanks to the generosity of Sir Thomas Gresham, a member of a prominent family of Norfolk merchants, who became financial adviser to Elizabeth I and made himself a considerable fortune in the process. Indeed, so rich and famous did he become that the Victorian economist Henry Dunning Macleod named after him the law that “bad money drives out good”: or, in other words, that when silver coinage is debased by people clipping bits off the edges or the mint adulterating it with lead, people will hoard their pure coins and spend the debased ones. (In fact, the principle was first postulated by Copernicus and even foreshadowed by the ancient Greek dramatist Aristophanes, but Macleod does not seem to have been aware of this.)

By the time of his death from a sudden stroke in 1579, Gresham was said to be the richest man in Europe. He had founded an important commercial centre, the Royal Exchange, obtained massive privileges for the famous overseas merchants’ guild, the Merchant Adventurers (to which he belonged, of course), and helped shape the financial and commercial policy of the Elizabethan state. Lacking any surviving legitimate children, he left his fortune, after providing for his widow and illegitimate daughter and making some bequests to the poor, to the Mercers’ Company and the Corporation of London in trust to found a college to provide free instruction to the citizens of London.

At the time, of course, there was no institution of higher education in the capital, so Gresham College became the first, and remained the only one until the 19th century. Sir Thomas made sure that, unlike the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge, its teaching not only focused on cutting-edge subjects but was also useful as well as academic. The subjects of the seven new professorships were astronomy, divinity, geometry, law, music, physic and rhetoric. These remain to this day, although commerce and environment have more recently been added, and rhetoric has been interpreted to cover all the humanities, an extension of which Sir Thomas might perhaps not have entirely approved given his emphasis on the practical and the scientific.

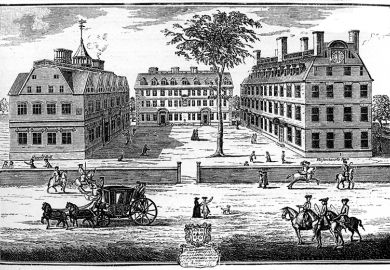

Over the following decades, the college enjoyed mixed fortunes, as some professors insisted on lecturing in Latin (a requirement abolished only in 1811), while others failed to deliver any lectures at all. A polemical tract issued on the institution’s 50th anniversary, Sir Thomas Gresham, His Ghost, imagined the founder looking down with disfavour on the fractious and disputatious professors and their failure to fulfil his intentions. However, what the academics lacked in dedication to teaching they made up for in energy in research. The college’s premises in Gresham’s former house in Bishopsgate (roughly on the site of what is now Tower 42, the former NatWest Tower) became the location for numerous experiments of one kind and another, and its professors gained enormous distinction in the scientific world. Some of them played a significant role in the founding of the Royal Society, which was based in the college until it moved to Crane Court in 1710.

It is not every academic institution that can boast, as Gresham recently did in advertising its professorship in astronomy, that “previous incumbents include Sir Christopher Wren”. Other major luminaries of the 17th century intellectual world who were Gresham post-holders include Robert Hooke (surveyor of London after the Great Fire of 1666 and, appropriately enough, Gresham professor of geometry) and Sir William Petty, the inventor of “political arithmetick” (although, oddly, at Gresham College he was professor of music).

Like most academic institutions, the college went through a period of decline in the 18th century and it was still a rather somnolent institution in 1860, when Charles Dickens arrived one morning to be greeted by “a pleasant faced beadle, gorgeous in blue broad cloth and gold”, who told him that the lecture he wanted to hear was to be delivered “in the theatre up-stairs, sir. Come at one and you’ll hear it in English.”

“Isn’t it given in Latin at twelve?” Dickens asked.

Audiences include an extraordinary range of people, from students to professionals and retired financiers. And, as I can attest, there is no shortage of experts

“Lor’ bless you, not unless there’s three people present, and there never is!” he replied.

Not surprisingly, when the founding of a university in London was discussed in the late Victorian era, Gresham College was sidelined. Although it had some distinguished professors, including the eugenicist and statistician Karl Pearson (professor of geometry between 1890 and 1894), there were also periods when the professorships were not filled at all, and it was not until the 20th century that the college’s fortunes finally revived. Perhaps, for whatever reason, there was a renewed feeling among distinguished figures that its professorships were worth applying for; certainly, vacancies became increasingly rare, eventually ceasing altogether.

Lecture attendances also improved after the inevitable suspension of activities during the Second World War. Who, for instance, could resist going to a series of lectures by the Gresham professor of music when the post was held by the jazz musician John Dankworth (1984-86), or by the professor of rhetoric when the incumbents included leading poets and critics such as Nevill Coghill (1948-53), Stephen Spender (1961-63) and Cecil Day-Lewis (1963-65)? Given this revival in the college’s prestige, it seems almost inevitable that the professorship of divinity should have been held variously by the bishops of Edinburgh, London and Oxford, and the professorship of astronomy by the Nobel prizewinning scientist Sir Martin Ryle (1968-69) and the current Astronomer Royal, Lord Rees of Ludlow (1975-76).

During the later 20th century there were numerous attempts to establish a relationship with the University of London, which itself was going through a period of restructuring and reform. But eventually it was agreed that Gresham should continue to be an entirely independent institution and, in 1985, the post of provost was created to provide academic leadership. In 1991 the City Corporation and the Mercers’ Company – which still underwrite the institution financially – ensconced the college in new premises at Barnard’s Inn, by Chancery Lane Tube station, where the Mercers’ School had been based until 1959. The post of academic registrar was also established to administer the affairs of the college, which, in 1994, became a limited company.

Nowadays the professors are appointed for a term of three years, renewable for a fourth, and are required to deliver no more than six lectures during the academic year, usually around one a month, and mostly in the evening – thus allowing them to keep their full-time day jobs. Attendance has in many cases outgrown the capacity of the half-timbered hall at Barnard’s Inn, so higher-profile lectures are often held in the much larger theatre of the Museum of London, near the Barbican. Lunchtime lectures have been added to the programme, and there are now several visiting professors as well, appointed to deliver short series. Some of the lectures gain considerable attention in the media – most notably, perhaps, those of Baroness Deech of Cumnor, Gresham professor of law from 2008 to 2012, on divorce, cohabitation and other topical subjects of public debate.

But the biggest change to the college in recent years has been its entry into the digital age. Full texts or extensive notes on each lecture have long been printed and distributed to the audience as they leave the lecture theatre, but Gresham’s website now contains more than 1,500 lectures and recordings, going as far back as 1984’s annual Special Lecture delivered by the historian Lord Blake, the biographer of Disraeli and chronicler of the Conservative Party. The site had more than 2.25 million visitors last year and the college is working hard to improve its reach via social media announcements, YouTube videos of lectures and smartphone apps. Sir Thomas Gresham, with his enthusiasm for the latest learning and his commitment to spreading it as widely as possible, would surely have approved.

The job of provost involves looking at the college’s offerings and making sure they are of the highest academic standard while also having a broad public appeal. The audiences that attend Gresham lectures consist of an extraordinary range of people, from parties of school students to undergraduates to professionals and retired City financiers. Based on the searching questions I was asked during the lectures I delivered as professor of rhetoric between 2009 and 2013, I can attest that there is also no shortage of experts.

This year’s programme of free lectures, as usual, covers a staggering variety of topics across an enormous range of disciplines. Speakers include the eminent constitutional historian Vernon Bogdanor, whose lectures on Britain and the Continent culminated in a lecture on the growth of Euroscepticism held on 20 May, immediately before the European elections. There are also lectures on, among other things, the palaces of Henry VII and Henry VIII; composers such as Haydn, Schubert and Messiaen; fashion and its relation to modernity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; offshore tax havens; quasars and black holes; polio; and blindness.

Over the years I’ve come, rather to my surprise, to have a close relationship with adult education. This was first established during my years as vice-master, then acting master of Birkbeck, the University of London’s centre for part-time evening students, and then at Wolfson College, where our students consist of a mixture of full-time graduates, mature undergraduates and part-timers. I hope this experience will enable me to ensure that Gresham College continues to flourish, matching – and perhaps even surpassing – the ups rather than the downs of its long and often surprising history.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?