The names Marlene Dietrich and Leni Riefenstahl conjure up distinctive associations. There is the provocative Dietrich who embodied the fashionable notion of “sex appeal” in the 1930 film The Blue Angel. Or one might think of Billy Wilder’s 1948 romantic comedy A Foreign Affair, in which she lends the morally and physically beaten Germans in Berlin a voice (notably in her songs about illusions for sale and the black market). In Riefenstahl’s case, one may perhaps think first of her propaganda films for Hitler (Olympia was named joint best film at the Venice Film Festival in 1938) and her post-Second World War photography of the African Nuba, followed by the deep-sea images she captured when, always keen on breaking records, she became the world’s oldest certified diver.

In Dietrich & Riefenstahl, Karin Wieland treats in parallel two lives with some striking similarities – such as a rigorous culture of one’s own body – and a good number of obvious, particularly political, differences. And, in these two women’s wake, we find numerous men who contributed to the highs and lows of 20th-century history and culture. In Dietrich’s orbit there were, for longer and shorter periods, the likes of Erich Maria Remarque, Ernest Hemingway and John F. Kennedy; in Riefenstahl’s Hitler, Albert Speer and Joseph Goebbels. Wieland offers abundant – and now and then overwhelming – material and produces a captivating chronological narrative that is rich in sources, although some of the more personal details from notes and letters may leave the reader with an uncomfortable sense of voyeurism.

Both women reinvented themselves time and again. After her move to Hollywood in 1930, Dietrich the actor became in due course a successful singer. One of the most fascinating chapters in this book focuses on her service with US forces during the Second World War, entertaining the troops. She was able to announce the success of the Allies in the Normandy landing to her all-male audience one evening, and, as quoted here, she offers a telling impression of life at the front when she writes about the icy-pawed rats that ran across her face in the tents at night. If she gave credit to the director Josef von Sternberg for her screen stardom and to Burt Bacharach for her musical success, her role in the fight for a liberated Europe was certainly all hers, and it earned her the Medal of Freedom in the US. The Germans, not surprisingly, were for a long time less appreciative of this aspect of her career.

Dietrich worked relentlessly to maintain her own myth; Riefenstahl, with reckless force, pursued the same ambition in the name of art. An actor with stamina but of limited ability, a technology-obsessed film director and finally a photographer, she “scripted her life”, as Wieland shows, “like a movie role”. The director who presented Hitler like a divine revelation and used extras from concentration camps was chosen by Time magazine as a German guest of honour at an event celebrating the magazine’s 75th anniversary in 1998. Wieland explores how she proved so convenient a choice as a feminist role model that the politics of the past could be pushed into the background. Riefenstahl was driven, unrepentant, in her own estimation gifted and therefore unloved, and her photography presented striking images of free sexuality. This work captivated a new post-war, post-rebuilding public despite the fact that, in a 1974 essay, Susan Sontag dissected Riefenstahl’s work on the Nuba for what it still was: “Fascinating fascism”.

This study works well on two levels: in addition to the richness of the material itself, it is engaging to trace how both women became part of cultural and political, national and international networks that shaped the 20th century. Wieland also achieves something that all too often gets lost: her book (translated from the German by Shelley Frisch) is a good read, spanning the First World War right into more recent history. There is, nevertheless, one aspect of the study one might consider disappointing: Wieland leaves it to readers to draw their own conclusions from the two biographies. What we are to think of themes such as the “New Woman” who came to the fore after the Great War; the politics that determined culture and therefore also the platform for creative reinventions; or the importance of – male – networks is for us judge. The emerging story is fascinating; but there persists a lingering sense of an opportunity missed to consider the (dis)similarities of two forceful 20th-century women in more depth.

Ulrike Zitzlsperger is associate professor of German, University of Exeter.

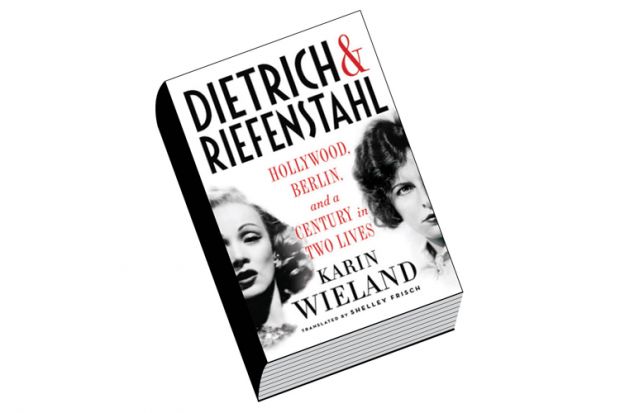

Dietrich & Riefenstahl: Hollywood, Berlin, and a Century in Two Lives

By Karin Wieland

Translated by Shelley Frisch

W. W. Norton, 624pp, £22.99

ISBN 9780871403360

Published 13 November 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?