If #AcademicsWithCats has taught us anything, it is that academics, like everyone else with an internet connection, love cats. Since its creation last year, the hashtag has generated thousands of posts of academics and their feline friends.

This week saw the announcement of the winners of Academia Obscura’s second annual Academics With Cats Awards, where academics voted from a shortlist drawn from more than 300 entries. Here’s the winner of Best In Show:

#ScholarTed is unhappy with his his latest draft of 'Posthuman Politics: The Role of the Feline' #AcademicsWithCats pic.twitter.com/bz3wiuBZBJ

— Dr. Kirsty Liddiard (@KirstyLiddiard1) November 18, 2015

The academic-cat relationship goes back some way.

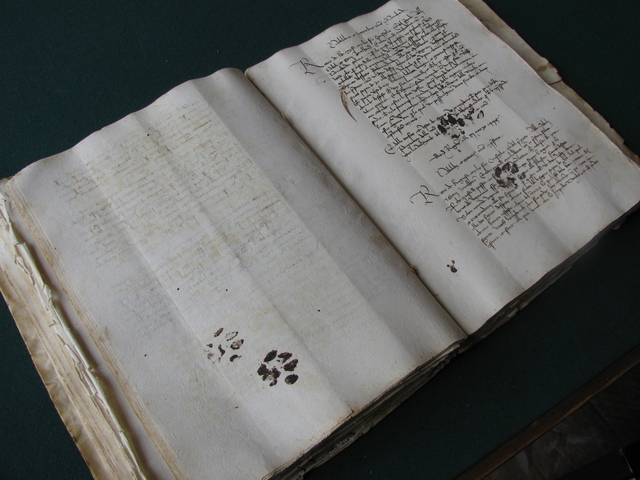

A couple of years ago, Emir Filipović, from the University of Sarajevo, was trawling through the Dubrovnik State Archives when he stumbled upon a medieval Italian manuscript (dated 1445) marked with four very clear paw prints.

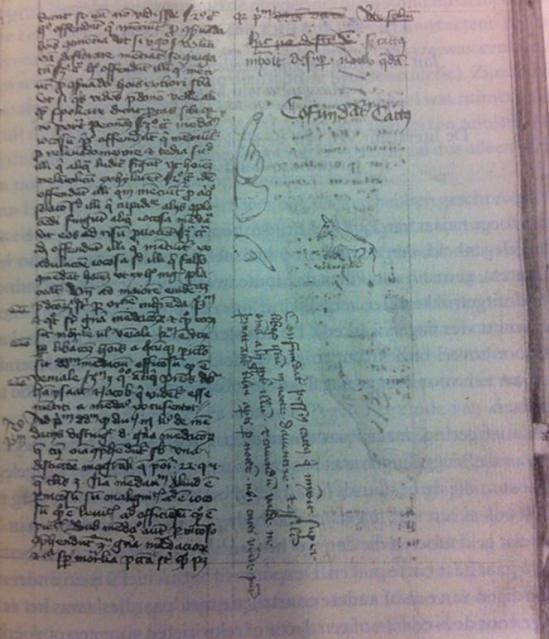

It could have been worse: around 1420, one scribe found a page of his hard work ruined by a cat that had urinated on his book. Leaving the rest of the page empty, and adding a picture of a cat (that looks more like a donkey), he wrote the following:

Here is nothing missing, but a cat urinated on this during a certain night. Cursed be the pesty cat that urinated over this book during the night in Deventer and because of it many other cats too. And beware well not to leave open books at night where cats can come.

Although occasionally ruining manuscripts, cats undoubtedly saved many hundreds more, by hunting mice that would have otherwise had a field day feasting on the paper.

One curious cat has outshone all others, becoming an academic legend in the process. F.D.C. Willard has published as both a co-author and, unbelievably, as the sole author on scientific papers in the field of low temperature physics.

The story goes that Jack Hetherington, an American physicist and mathematician, needed to eliminate the use of the royal “we” in a paper, so he added his cat as co-author.

Concerned that colleagues would recognise Chester’s name, he concocted a pen name: F.D. for Felis domesticus; C for Chester; and Willard after the cat that sired him. The joint paper was published in Physical Review Letters in 1975 and has been cited about 70 times.

When the reprints arrived, Hetherington inked Chester’s paw and sent a few “signed” copies to friends.

One was sent to a physicist who later recounted that colleagues wished to invite Willard to a conference because “he never gets invited anywhere”. The physicist produced his copy of the paper to the organising committee and “everyone agreed that it seemed to be a cat paw signature”. Neither Willard nor Hetherington was invited.

Hetherington recalls: “Shortly thereafter a visitor to [the university] asked to talk to me, and since I was unavailable asked to talk with Willard. Everyone laughed and soon the cat was out of the bag.” Terrible pun presumably intended.

Some years later Hetherington and his collaborators disagreed on how certain ideas should be presented in a paper. With none of them ultimately willing to sign off on the finished product, they pulled Willard out of retirement and named him as the sole author of the paper, ultimately published in the French journal La Recherche.

Willard was considered for a position at the university and, in honour of his contribution to physics, APS Journals announced on 1 April 2014 that all feline-authored publications would be made open access. “Not since Schrödinger has there been an opportunity like this for cats in physics,” the announcement reads.

More by this author: The weird world of academic Twitter

Others, like Jordan the library cat, have taken a less ambitious approach to academic life. He leaves his home at the University of Edinburgh friary every day to hang out in the library, where he is petted by students and sleeps in his favourite turquoise chair. Jordan has his own facebook page and has been issued a library card.

When cats aren’t contributing to academic life, they are themselves the subject of much interesting research, including a much-publicised study suggesting that your cat may wish to kill you (the study in question simply says that domestic cats share personality traits with lions, but that doesn’t make for great clickbait).

Other papers include “Demography and movements of free-ranging domestic cats in rural Illinois” and “How cats lap: water uptake by Felis catus”.

For us humans though, the most interesting, and pressing, cat research investigates their propensity for spreading mind-controlling parasites. You see, cats carry a parasite called Toxoplasma gondii, which alters the behaviour of animals to make them less afraid of predators (and therefore more likely to be killed, eaten and used as a conduit for further propagation of the parasite).

The slightly eccentric Czech scientist Jaroslav Flegr has made such research his life’s work, and since a “light bulb” moment in the early 1990s he has been investigating the link.

More by this author: The hidden silly side of HE

We’ve known for years that infection is a danger during pregnancy and a major threat to people with weakened immunity, however the research of Flegrs and others suggests that infected humans are more likely to be involved in car crashes caused by dangerous driving and are more susceptible to schizophrenia and depression. And all that is to say nothing of the as-yet-unexplained link between cat bites and depression.

Whether or not your cat is trying to kill you or depress you, they are still cute, and looking at cute pictures has been shown to improve your productivity.

You can get your fill by mindlessly scrolling through #AcademicsWithCats, or checking out the winners of the Second Annual Academics with Cats Awards.

Glen Wright blogs at Academia Obscura and tweets at @AcademiaObscura. His book is crowdfunding now.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?