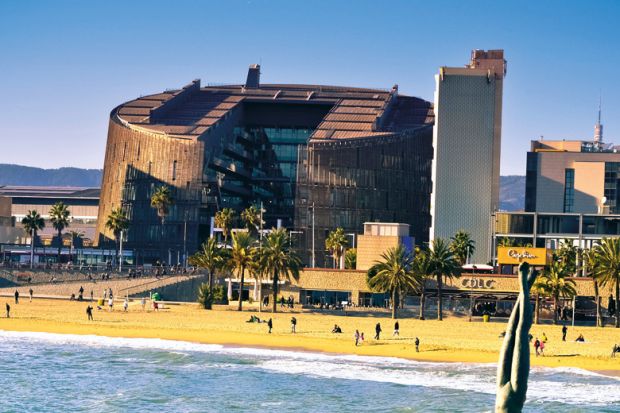

Few laboratories can surely match the views from Barcelona Biomedical Research Park on the city’s busy beachfront.

From the sun-dappled balconies of the modernist €120 million (£93 million) institute, scientists can watch boats sail out from the Olympic Port, swimmers take a dip in the Mediterranean and tourists zip along the seafront promenade on motorised scooters.

“It’s a wonder we get any work done at all,” joked Angel Lozanos, vice-president (research) at Pompeu Fabra University, on the view from the institute, which was established by the university alongside Barcelona City Council and the Catalan government in 2006.

But plenty of work has been done at the institute, which celebrates its 10th anniversary later this month. About 1,500 staff from seven independent research organisations are based at the institute, which has become one of the largest biomedical research centres in southern Europe, producing 1,130 scientific publications last year, double its 2006 total.

With more than 100 research groups working in close proximity to each other – investigating everything from cancer and neuroscience to evolutionary biology and epidemiology – there are some similarities to London’s Francis Crick Institute, which aims to foster the same ethos of cross-disciplinary working found in the Barcelona lab.

With scientists from about 60 countries at the institute – almost a third of researchers are international – it is one of the few places in Spanish academia with a truly international workforce, said Professor Lozanos.

“We can’t compete on wages with places like Switzerland, where they seem to have almost infinite money, but people want to come here, partly due to the quality of life on offer,” he explained.

“People are willing to take a 20 per cent salary cut to come here because it’s Barcelona.”

That success in recruiting internationally is also due to the institute’s ability to sidestep some of the more restrictive state bureaucracy that critics say is hampering Spain’s ability to attract top talent.

Under Spanish law, foreign academics must have their PhD ratified by the education ministry – a process often lasting years, which stops many top international scholars from moving to Spain.

As a research organisation created outside the rules binding most universities, Barcelona’s research park can employ international staff more freely, and also pay them higher salaries than normal academics whose Civil Service status makes them subject to national pay structures.

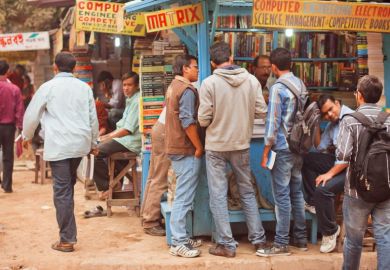

“When I did my PhD here in Barcelona, there was one foreign PhD in my cohort, but now the problem is recruiting enough Spanish candidates,” said Cristina Pujades, associate professor at Pompeu Fabra’s department of experimental and health sciences, and research delegate at the institute.

“My six PhD students are all foreign, including two Indian students,” Dr Pujades added.

The institute’s lingua franca is now English, with the international research community pushing each other to succeed, she explained.

“It’s fantastic to hear people say ‘I’m having a paper published in Science’ as it pushes people on to work that bit harder.”

Having such a vibrant international research community – it has its own orchestra and annual beach volleyball competition – is one of the main reasons why Barcelona outperforms the rest of Spain in terms of research and higher education, many argue.

Three of the city’s universities are ranked in the top 200 of Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings, with the Autonomous University of Barcelona (146th) just ahead of Pompeu Fabra (joint 164th) and the University of Barcelona (174th), whereas no other Spanish university makes the top 300.

If Catalonia were assessed in its own right, it would be the third-best country judged on European Research Council success rates (behind Belgium and Luxembourg), said Arcadi Navarro, secretary for universities and research for the Catalan government and a professor in genetics at Pompeu Fabra.

“This is an enormous achievement when you consider the [relatively youthful] history of our institutions,” said Professor Navarro. Indeed, Barcelona’s universities have improved their performance in spite of cuts brought about by Spain’s economic crisis, which has led to a brain drain of many of its top scientists.

However, Catalonia’s universities are still held back by rules dictated by Madrid, said economist Andreu Mas-Colell, a former ERC secretary-general, who spoke to THE earlier this year about the potential benefits of Catalonian independence from Spain.

Proposals to reform university governance – including the end of rectors elected by staff and students – suggested by a commission led by Luis Garicano, a London School of Economics economist, have not progressed in any way since they were put forward three years ago, Professor Mas-Colell said.

“Universities would progress much better if they could choose their own form of governance, moving to a board-led system as seen in places like Finland,” he said.

Reforms are unlikely to occur anytime soon given Spain’s current political gridlock: the country is entering its fifth month without a government since elections in December produced no clear winner.

“We know where we need to go to improve, but the legal framework binding universities leaves us in a straitjacket,” said Professor Mas-Colell.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Barcelona rises above Spain’s education malaise

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login