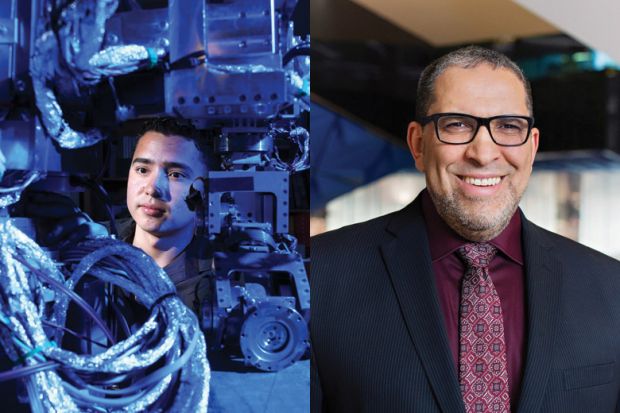

Mohamed Lachemi is the kind of immigrant Canada wants. “I came to Canada as an international student exactly 30 years ago,” he tells Times Higher Education. “Canada attracted me not just to study but to stay.”

He is now the vice-chancellor of industry-focused Ryerson University in downtown Toronto and, in line with federal plans, wants to become “more aggressive” in attracting international students to his institution. Ryerson aims to double its numbers over the next three to five years.

In England, the number of new international students has begun to decline following the ending of post-study work visas and a general toughening of the immigration system.

Meanwhile in the US, there is anecdotal evidence that campaign rhetoric from Donald Trump is causing some potential applicants to think about other study locations.

“The political situation in the US is helping us at the moment,” says Matt Stiegemeyer, director of student recruitment at Concordia University in Montreal. He recently met two prospective students – Muslim twins from Brazil – who were now looking at Canadian universities after having been put off the US by Mr Trump’s pronouncements.

But in Canada, official policy, as well as political rhetoric, is far more welcoming. In 2014 the country set out plans to attract 450,000 international students by 2022, roughly double the numbers in 2011.

The policy has cross-party support: it was launched under the previous Conservative government and has survived the election of a new Liberal government in October last year. Indeed, the Liberals, who felt that the previous administration was not welcoming enough, were elected with a pledge to again make the time that foreign nationals spend studying in Canada count towards any application for citizenship.

They point out that Canada’s ageing population makes new immigrants crucial. Population projections forecast that by 2030, even with migration, close to one in four Canadians will be over 65, a similar proportion to Japan today. The demographic problem will be particularly acute in relatively remote Newfoundland and Labrador, which could actually see its total population shrink.

So far, Canada appears to be on track to achieve its 450,000 goal. Since 2011, enrolments have increased from about a quarter of a million to almost 340,000 in 2014, according to the Canadian Bureau for International Education. If absolute growth continues like this, the 450,000 target for 2022 will be smashed.

Of international students in the country, almost one in three was from China, and just over one in 10 from India. Only 3.7 per cent hail from the US.

It should be noted that these figures, and the federal target, include all levels of international student, from primary school upwards. However, the majority – 58 per cent – are university students, and this is a higher proportion than average in the previous decade, so it seems that Canada is adding international students at the tertiary level just as quickly as, if not faster than, it is at other education levels.

Seeking a balance

But there are reasons why this dramatic growth may falter. For a start, not every university is as keen on boosting foreign student numbers as Ryerson. “Yes, we’re interested in growing international students, but we’re now in some faculties close to about 30 per cent [international students as a proportion of total enrolments],” says Judith Wolfson, vice-president, international, government and institutional relations at the University of Toronto. “We’re pretty close to where we want to be.”

More important to Toronto is getting a more balanced mix of countries, particularly with economic and demographic clouds hanging over the future of recruitment from China, says Wolfson. More than half the university’s international students come from China (including Hong Kong).

“Frankly, the most important thing for us to grow is [student numbers coming] from the United States,” Wolfson says. “It’s quite remarkable that we have this huge country beside us and…50 per cent of all our new faculty hires are from outside Canada, the majority of whom of course come from the United States. But undergraduate students [in the US] don’t know anything about Canada. This is a Canadian problem, this is not a University of Toronto problem.”

US students “assume it’s very cold, when in fact Toronto is south of northern California”, she claims. “We are putting a huge emphasis on increasing our proportion of American students. Tens of millions are within a nine-hour drive of Toronto.”

Meanwhile, in French-speaking Montreal, McGill University appears to have already cracked the US market. About one in four students is international, and the US is the best represented country among them. There are more students from France than from China.

“We’re sort of Europe-lite for Americans,” says Kathleen Massey, McGill’s registrar, although she adds that the university does not “necessarily” plan to expand its numbers.

The University of Toronto certainly has the potential to attract more US students, she believes, “but these are deep roots that take years” to build up. In part, strong links with the US are a legacy of when Montreal was Canada’s dominant city, before the threat of Quebecois independence spurred the rise of upstart Toronto.

In Quebec, most of the lucrative fees that international students bring in are redistributed by the provincial government, largely eliminating the financial incentives universities might have for increasing enrolments.

This system is “pretty galling”, according to Graham Carr, vice-president for research and graduate studies at Concordia University, where 16 per cent of students are international.

“This is a sore spot for McGill and Concordia,” he says, adding that it undercuts the broader national policy of attracting more international students.

Furthermore, Canada’s international students are not necessarily graduating into the kinds of high-value jobs that the government envisages. A secret government report, obtained by The Globe and Mail earlier this year, found that most international graduates taking advantage of a three-year post-study work programme were in low-skilled service sector jobs earning less than C$20,000 (£10,600) a year.

Canadian universities are now for many students the first step in an immigration process: McGill employs immigration lawyers to help students applying for courses and offers information sessions on campus about applying for permanent residence, while Concordia also offers immigration advice. But what kind of introduction to the country are universities providing?

Problems assimilating international students into wider campus life are common on Western campuses, and Canada is no exception. Fifty-six per cent of international students in Canada say they have no Canadian friends, with students from North Africa and the Middle East particularly isolated from locals.

Most of the universities THE spoke to stressed how Canada’s multicultural cities provided a home from home for foreign students, rather than offering any programme of assimilation. Ryerson’s Lachemi pointed out that in Toronto, where about half of residents are born abroad, international students can easily communicate in their native language and find familiar food.

Universities tend to use other international students, rather than those from Canada, to help new arrivals settle in. At York University in Toronto, international students are told how to navigate student life even before they arrive in Canada by already enrolled compatriots if they are not comfortable speaking English.

“It’s a way of building up a connection before they come to Canada,” explains Prince, a second-year student who grew up in both India and Italy.

Yet at Concordia, international students are treated to a traditional if rather gruelling introduction to Canadian life – cross-country skiing.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login