The Higher Education Policy Institute and Times Higher Education joined forces for an essay-writing competition on UK higher education’s place in the European Union. There was a £200 prize for the best entry on each side of the argument, and these essays are printed in full below.

Pro-remain winner

Count the brains, not the pennies: Brexit and higher education

Sarah St. John, PhD student in the Department of Education, University of Glasgow and university administrator at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute

As perhaps the most transnational environment to be found on British soil, the UK university could be one of the worst suffering victims of a Brexit. Its impact on higher education is a multi-faceted argument that often focuses from both sides on economic consequences, but a reduced European presence within the faculty of UK higher education institutions risks graver consequences.

Without the significant proportion of EU nationals currently contributing to the total composition of academic staff in British HEIs, including PhD-student teachers, we can imagine buzzing corridors of academic departments across the UK coming to echo the frantic typing of the lonely British scholars, desperately compensating the lost publications of their EU counterparts.

Really what would happen is that fewer EU nationals would apply for posts in UK academia and they would consequently be offered to their British counterparts. This might seem like an optimal situation for British scholars, but it is not for the university.

While inside the EU, UK universities are in a privileged position that allows them to cherry-pick from a pool of the best scholars across all member states of the European Union. With promising career prospects and good resources as well as a renowned academic reputation, the UK is an attractive destination for European scholars, which makes for a happy marriage between UK universities and EU scholars.

Furthermore, due to difficulties entering academia in their own states and the eventual positive prospects within the UK system, European scholars are more likely to take on more of the numerous non-permanent posts than British scholars, and to accept the sometimes sub-standard conditions they come with.

European scholars are also attractive to UK universities for the broader readership they attract in a wider selection of journals, and for the international research networks they bring, all of which have a positive influence on the research excellence framework (REF). Research carried out with international collaborators is noted to have 50 per cent more impact than research carried out with domestic collaborators.

So, in this case, it is not about the money. It is about the very rationale of a university to produce high quality research and teaching, and in this respect, Brexit reduces British higher education’s ability to function at its full potential.

The best British scholars will already be entering the UK academic world with or without EU scholars, so the posts that would have been occupied by shining EU scholars would instead be awarded to British scholars who would not have been previously accepted. While this is good news for the otherwise rejected scholars, it cannot be denied that universities in the UK would be settling for a lower quality of scholarship. And if it became easier for British scholars to secure an academic post without having to first fight off the eager EU scholars in a hunger-games-style race to the permanent lectureship, would they continue to endeavour to excel quite as much as they are forced to now?

It could be said that competition from EU counterparts currently keeps British scholars on their toes.

The consequences that this potential shift away from the relatively high recruitment of EU scholars in academic posts could pose on British institutions are numerous. It is unclear whether the UK would experience a sort of "reverse brain-drain" of scholars returning to Europe.

This is bound to depend on the ease of living outside of the European Union. It will perhaps be easier for those in permanent positions, but those holding fixed-term contracts may find their permanence in the UK challenging. For sure, there is a risk of brakes being applied to the current brain-drain from the EU to the UK. This will be beneficial for EU universities, which will be more likely to retain their scholars and better their knowledge economies, but a reduced brain-drain to Britain cannot be positive for the British knowledge economy.

British academia can compete well on the global level thanks to its ability to attract the best scholars from Europe. Being able to compete globally means having a capacity to build an internationally recognised intellectual reputation through publication in wider-read journals and to be able to apply and win external research funding from wider sources, which in turn facilitates the provision of resources for advancements in medical, technological, cultural and intellectual research.

Development in these areas sets a nation a cut above the rest not only in the commercial world, which helps strengthen the financial economy, but also from the perspective of developing a deeper understanding of the cultural world. This assists in making sense of complex issues surrounding terrorism and immigration.

Moreover, it can be said that the wider British society is benefitting from this abundant intellectual community at its disposal.

The rich profile of scholars in British institutions is responsible for the education of young people in Britain, principally those at university following degree programmes, but they are also responsible for teaching the teachers who will go into the local schools across Britain, shaping and creating an identity in the learning population across the country, which ultimately fosters the intellectual and national identity of the nation. For this reason, it is imperative that the brightest scholars are found in UK institutions, and that these scholars are not predominantly British in order for an open-mindedness and cultural awareness to seep into British society.

Education shapes the way a population perceives and understands the world. Does Britain want to face the long-term consequences of an inward-facing, potentially intolerant society? This will do the nation no favours in the long run.

A society’s education is too important to jeopardise. It is not money making the world go around; education makes the world work by creating educated individuals who know how to make the most of the money available.

So rather than counting the pennies lost to Europe and looking for a way out, Britain should worry about the potentially significant intellectual loss that will heavily dent British higher education if Brexit becomes reality.

Pro-leave winner

In defence of Brexit: no need for universities to fear the future or democracy

Lee Jones, senior lecturer in international politics at Queen Mary University of London, and Chris Bickerton, lecturer in Politics at the University of Cambridge

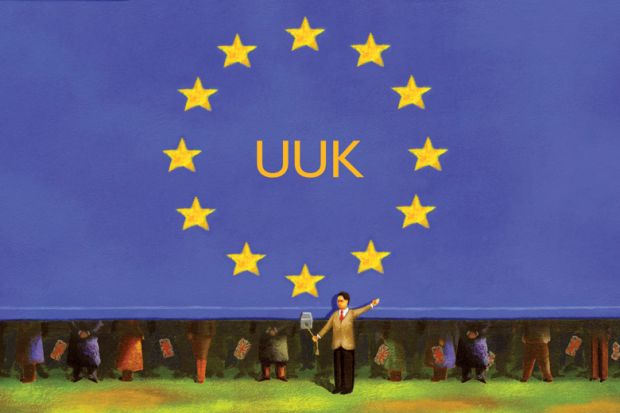

The debate on Britain’s European Union membership has been risible, dominated by "Project Fear" on both sides. Sadly that is also true of Universities UK’s Universities for Europe campaign, which unilaterally commits Britain’s universities to the Bremain side, warning of disastrous consequences for higher education if Britain leaves.

Most of UUK’s claims simply don’t stack up. Most importantly, our fate would not be determined automatically by Brexit, but rather by what the British people democratically determine to do afterwards.

UUK’s entirely utilitarian case against Brexit is as follows: over 200,000 UK students have benefited from the Erasmus programme; over 125,000 EU students currently study at UK universities, generating £2.27 billion for the UK economy and 19,000 jobs; 15,000 of our academics are from other EU states; and the UK does well from EU research funding. UUK also strains (unconvincingly) to attribute the total economic activity universities generate to "EU support".

Aside from the arrogance involved in committing universities en masse to a political position without any consultation with scholars or students, UUK’s case against Brexit is fundamentally weak.

The Erasmus statistics are irrelevant. Participation in the programme is not tied to EU membership. It currently has 927 partner institutions in 37 countries – including but not limited to the EU’s 28 member-states.

EU students and staff certainly enrich our campuses in every sense. But why should this end with Brexit? They come to Britain because our universities are world-class institutions that, relative to the vast majority of continental institutions, are thriving. EU students keep coming despite massive fee increases, while the Euro-crisis has only intensified the influx of talented European scholars.

Post-Brexit, student and staff migration would remain possible: student visas will still exist, and a prospective points-based immigration system would doubtless maintain access for highly-educated scholars.

Indeed, the flexibility that Brexit would create around immigration policy could correct serious inequities caused by EU strictures. Since EU member-states cannot control intra-EU migration, any UK government wishing to reduce immigration must curb non-EU immigration. Accordingly, EU citizens are free to enter the UK, but many non-white non-EU citizens face enormous hurdles.

This increasingly prevents British universities recruiting the best and brightest students and staff regardless of national origin. Current and prospective students face regular harassment from the UK Border Agency, while non-EU staff like Paul Hamilton and Miwa Hirono have been deported and others endure daily surveillance to meet strict visa rules. Doubtless, this ultimately reflects anti-immigration sentiment. But EU membership has only fuelled these attitudes by reducing national control over migration policy.

Most importantly, if migration rules or EU student fees did change after Brexit, crucially, that would not be an automatic side-effect of the referendum. How could it be? The referendum is purely on EU membership – it does not commit subsequent governments to any other policy position.

Decisions on these and any other issues would be made by democratically elected governments and thus, ultimately, by the British people. Claims that Brexit will definitely produce xenophobia tells us more about what Britons think of each other than anything about the costs and benefits of EU membership.

As for research funding, UUK state that the UK received £687 million in EU research funding in 2013/14, rightly stating that we do disproportionately well, securing 15.5 per cent of funding under FP7 and 20 per cent of European Research Council awards. This, UUK rightly says, fosters positive international mobility and collaboration.

But let’s put this in perspective. UK universities’ total research income in 2013/14 was £11.2bn. The EU supplied just 6.1 percent of this. Its loss would hardly kill off British academia.

Britain is successful in securing EU funding because it has such a strong scientific base; it is not EU funding that created that base. And again, there is nothing to stop the British people deciding to increase research funding post-Brexit, reversing the long-term cuts that account for the EU’s growing share. Again, it is a decision for us, not something pre-determined by the referendum outcome.

Moreover, it is not even obvious that Brexit would sever access to EU research funding. Non-EU states like Switzerland have negotiated agreements to give their universities access to Horizon 2020 funds. They are also members of the European Research Infrastructure Consortium, where since 2013 they have enjoyed equal rights with EU members.

If Israeli institutions can win €203m in EU grants, why couldn’t Britain continue to access international funding and participate in cross-border collaborative research? Suggesting that Brexit would end this collaboration assumes that European researchers will somehow be unable to find new ways to work together or will even shun their British counterparts to "punish" them. This entirely ignores the history of scientific collaboration, where even dramatic obstacles like wars did not deter cross-border cooperation to learn more about the world.

Where is the faith in the internationalism of scientific research among academics today?

Most importantly of all, when scientists wail that their "lab would fall apart" outside the EU, the ultimate response must be: the referendum isn’t about your lab; it is about democracy. Its consequences, either way, are so vast and wide-ranging that this is the most significant political decision that will occur in our lifetimes. We all have our own interests, including our research, but we are also citizens. We must look further than our own nose ends and think about more than pounds and pence in reaching our decisions about fundamental political issues.

This referendum is an opportunity for the British people to take their future back into their own hands. That future, crucially, is not pre-determined by the referendum outcome. If we want more open borders, more internationalisation, and better funded research, we can still have them. It will be up to us to decide collectively.

Rather than hiding these preferences behind fake arguments about economic and scientific necessity, academics should fight to win over the public to their point of view. That way, Brexit could not only restore national democracy but also enhance the role of scholars in public life.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?