View and/or download a high-resolution version

Governments and universities must recognise that there is a “price limit” where tuition fee rises will start to hit student access, even in those nations with income-contingent loans, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s influential director for education and skills.

Andreas Schleicher, speaking at the launch of the OECD’s annual Education at a Glance report providing data on education in member nations, also said that tuition fees charged at US private universities bore “no relationship” to the quality provided for students.

The OECD’s figures, from 2013-14, show that US private universities charge the highest tuition fees ($21,189, or £16,001), followed by UK institutions ($9,109) and private institutions in South Korea ($8,554).

The UK (where fees of £9,000 a year are charged by English universities) has the most expensive public universities in the world, according to the OECD.

However, the structure of repayments is also a crucial factor in the loan costs faced by graduates, in addition to overall debt levels.

The OECD and Mr Schleicher are long-standing advocates of tuition fees supported by income-contingent loans, seeing such systems as a means to increase funding for higher education while expanding access.

England, which has a system of income-contingent loans, is to allow universities to raise fees in line with inflation, from the current £9,000 maximum to £9,250 in 2017. In Australia, which has led the way on income-contingent loans, the administration led by former prime minister Tony Abbott planned to remove caps on tuition fees, but this plan was thwarted by political opponents.

Mr Schleicher warned that “England needs to continue to watch out that the smartest and not the wealthiest students get access to the best education”.

He added that in England “costs are high” and “students have a high debt burden”.

“That is an issue to consider,” he continued. “In our assessment for the moment, the system [in England] is working well. It gives a lot of people the chance to study. But it’s something to watch for.”

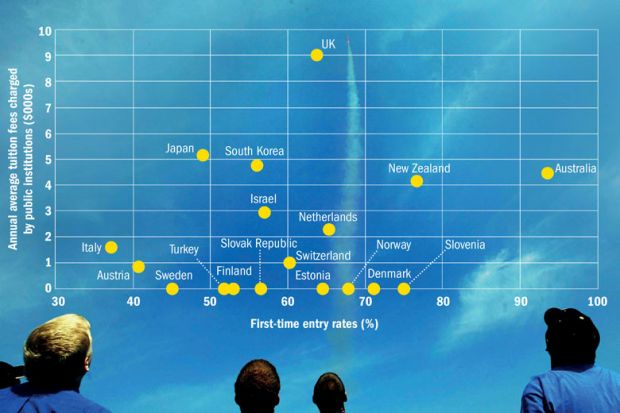

The OECD’s report says: “Countries with a low level of tuition fees do not appear to achieve better access to tertiary education than those with higher fees.

“Australia, Denmark, New Zealand and Slovenia all have first-time entry rates to tertiary education above 70 per cent for national students, but Denmark and Slovenia have no tuition fees, while public institutions in Australia and New Zealand [both with income-contingent loans] charge average annual tuition fees of over $4,000.”

Asked by Times Higher Education if, internationally, there was a limit to how much income-contingent loans could bear in terms of the burden of debt and repayments for students, Mr Schleicher said: “It’s a very important question. One thing is clear: the demand for higher education is going to continue to grow because the returns [in terms of higher earnings] are going to be good.

“The approach to share the resources between the beneficiaries and the taxpayers is the right one…having income-contingent loans in our view is the best way to actually get that balance right.”

But he added: “The question I have, when I say we have to watch out for this, is the price limit. One of the things that we’ve observed around the world is as soon as there’s money in the system, universities are very good at finding ways to charge that money.

“In the case of the US, for example, I would go as far as saying there’s no relationship between the money universities charge to people in private institutions and quality of services they provide to students.”

Mr Schleicher continued: “That’s where my worry comes from. Can you prevent that price structure [from] skyrocket[ing] and [making] it impossible, even with income-contingent loans, for those students who are best qualified to get the best service?”

He said that universities were “obliged to find pricing structures that meet the costs and the relationship with added value” for students.

In terms of overall funding for higher education as a percentage of gross domestic product, the OECD’s figures showed that the US is still highest (2.6 per cent, split between 1 per cent public and 1.7 per cent private funding, allowing for rounding), followed by Canada (2.5 per cent, split 1.3 per cent public and 1.2 per cent private), Chile (2.3 per cent, split 1 per cent public and 1.4 per cent private), South Korea (2.3 per cent, split 0.9 per cent public and 1.3 per cent private) and Estonia (2 per cent, split 1.9 per cent public and 0.2 per cent private).

The UK spent 1.8 per cent of GDP on higher education (split between 1.1 per cent public and 0.8 per cent private), above the OECD average of 1.6 per cent.

The OECD’s report also features data on international student recruitment at master’s and PhD level, showing the lead destination nations as the US (26 per cent of OECD total), the UK (15 per cent), France (11 per cent), Germany (10 per cent) and Australia (8 per cent).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Countries’ fees must not ‘rocket’ past ‘price limit’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login