Grégoire is in the second year of a master’s degree in engineering at a Parisian grande école. He does not want to be in my class. He rolls his eyes when I announce the next task and returns his gaze to his laptop. He rarely participates in class activities or group discussion.

Grégoire and I would both be happy if he were somewhere else entirely. He is in his twenties, and if he would prefer to just try his luck in the final exam, it seems to me that he is old enough to take that decision. He has already told me that he feels the class will be of no use to him in his future career as a software engineer.

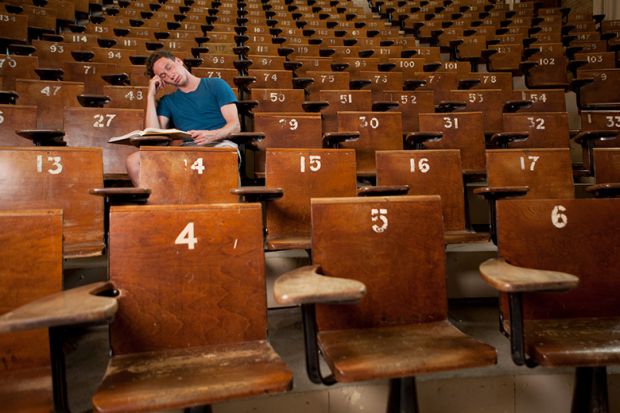

Yet institutional rules state that he must attend to avoid failing the compulsory language module. In the various Parisian universities and fee-paying grandes écoles where I teach English, students automatically fail if they have more than three unjustified absences in a semester. As a result, about half of the 20 or 30 students who attend each class seem deeply uninterested.

A mathematician I taught last year had spent time working in the US and thus spoke English almost flawlessly. Yet, as is often the case on university language courses, he was placed in a group whose abilities were far from homogeneous, so my teaching was necessarily pitched at a level that was pointlessly low for him. Nonetheless, “presence and participation” formed a quarter of his final grade for the class.

I totally agree with Bruce Macfarlane that such infantilising of students is both counterproductive and misdirected (“Should student attendance in classes be compulsory?”, News, 20 October 2016). “Question them,” said my boss at one of the top five grandes écoles. “If a student was absent the previous week, ask why in the next class.” But the entrance exam to these institutions is highly competitive. The students are clearly self-motivated. Why should they be forced to explain their absences? If these adults were treated as such and allowed to choose whether to attend, I would have a core group of enthusiastic students and could properly adapt my teaching to their needs and interests.

Part of the joy of teaching in higher – as opposed to secondary – education is that one is (in theory) teaching only those keen to learn. Yet instead I find myself wasting class time waiting for Myriam and Maxime to stop talking, or telling Cédric off yet again for being disruptive, spoiling it for those who do want to learn. Having to threaten a grown man that I’m going to move him away from his friend if he doesn’t stop giggling seems an odd way of dealing with highly intelligent students.

I have tried a range of different activities to pique my students’ interest. More recently, I have fallen back on a cocktail of sarcasm, shame – and sweets. But my students are not stupid. My saying “If you behave like a 12-year-old, I’ll treat you like a 12-year-old” is just as ridiculous as offering a sticky toffee for the highest score in a vocabulary quiz (although they always accept their prize). For a while I enforced a hard-and-fast “no screens in class” rule, but eventually decided I would rather they ignore me silently than nosily, by chatting with those sitting nearby.

Macfarlane is also right that it is ridiculous for any academic to be “so precious and sensitive” as to take it as an act of disrespect when a student does not turn up for their class. I do not take it personally if individuals don’t find my classes useful or engaging. What is dispiriting is being confronted every lesson with their blatant lack of interest.

Their reluctance to participate in small-group activities is frustrating. Their sighs of boredom when I hand out my carefully prepared resources are disheartening. I feel like I’m wading through treacle to reach the end of the lesson.

The author wishes to remain anonymous. None of the names used in this article are real.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Battle of wills and will nots

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login