It’s been said that we are living in an era of “post-truth” politics. Factuality and honesty do not have the traction that they once did; they may even be irrelevant. The 2016 US presidential election confirmed this, but also strongly suggested that post-truth politics applies only to men. Take “pussygate”, just one of the many reports of misogynous behaviour to swirl around Donald Trump’s campaign: no sooner did several women verify Trump’s own claims about his behaviour than he disparaged them as liars. No US political contest was so thoroughly fact-checked, and by all tallies, Trump had a higher rate of fibs than Hillary Clinton. Yet it was Clinton whose honesty was held to account. “Lock her up,” Trump’s supporters chanted, while Trump was handed the keys to the White House.

Rarely does an academic book address its moment so precisely as Tainted Witness. Drawing on examples that range from the 1990s to the present, Leigh Gilmore aims to explain why women are chronically mistrusted, and why judgement, whether rendered by the legal system or the court of public opinion, “falls unequally on women who bear witness”.

“Judgment”, Gilmore writes, “has a bodily connotation of viscosity and is couched in a rhetoric of animate gunk: reputations are tarnished or smeared, critics sling mud and throw dirt, shit hits the fan.” Don’t we know it. Her premise that “women encounter doubt as a condition of bearing witness” has been substantiated all too well by recent events.

Gilmore’s extensive work on life writing and feminism includes two books – The Limits of Autobiography: Trauma and Testimony, and Autobiographics: A Feminist Theory of Women’s Self-Representation – as well as an edited volume, Autobiography and Postmodernism. Along with scholars Sidonie Smith, Nancy K. Miller, Gillian Whitlock and others, she has developed a framework for understanding life writing – including autobiography, memoir, diaries, journals, letters and many hybrid genres – as a rich and evolving tradition descending from Augustine’s Confessions to Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl.

With Tainted Witness, Gilmore homes in on the writing and speech of women who bear witness. “Women’s testimony is frequently associated with unreliability because it is women’s testimony.” This maddening circularity explains why many women hesitate to report abuse. In addition to facing personal attacks, women who allege sexual violence or harassment will almost certainly face one of two lines of argument: “he said/she said” or “nobody really knows what happened”, both of which, Gilmore asserts, signal that the pursuit of truth will be abandoned as “unknowable”.

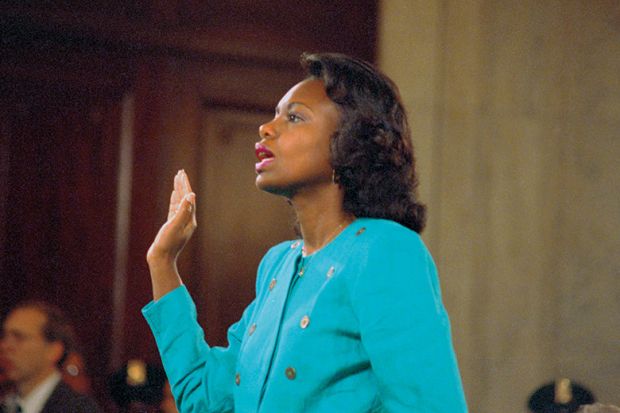

According to Gilmore, it was law scholar Anita Hill’s 1991 testimony to the US Senate’s Judiciary Committee about sexual harassment that she said she had experienced when working for Clarence Thomas – now a member of the US Supreme Court – that inaugurated “a new era in doubting women in public”. Even as women were “increasingly present and credible on a public stage”, they were undercut when they demanded equal rights and protection under the law. Those who watched the dignified Hill address a panel of older white statesmen badgering her to repeat tales of pubic hairs on Coke cans and Long Dong Silver will never forget it. The hearings were, as Gilmore puts it, “both vivid testimony about sexual harassment and a proximate and public reenactment of it”.

Gilmore’s intersectional analysis reveals how gender is inflected by race, nationality and class to influence the way testimony is evaluated. When Thomas indignantly described the questioning he received during his Supreme Court confirmation proceedings as a “high tech lynching for uppity blacks”, he shifted the frame from sexual harassment to racism, from his own conduct to the conduct of those white men interrogating him, thus sidestepping Hill’s charges. Gilmore shows how Hill “became collateral damage in a conservative Republican strategy to place an anti-affirmative action African American justice” on the Supreme Court.

Hill’s claims could have been verified, but her corroborating witnesses were not permitted to speak. She immediately became the subject of scandal, described in print as “a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty”. Gilmore keenly observes that the temporality of scandal is acceleration, but justice is protracted. Twenty-five years later, all of Hill’s assertions appear to have checked out; by contrast, many have claimed that Thomas committed perjury.

The cycle of scandal was different for Rigoberta Menchú, the Guatemalan political activist who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1992, only to have the accuracy of her 1983 book I, Rigoberta Menchú questioned by the likes of The New York Times, which ran a front-page story about her under the headline “Tarnished Laureate”. (More smears, more gunk.) She was eventually vindicated when a documentary film-maker and a criminal court corroborated her work. Menchú’s testimony, Gilmore writes, “immured as it was in scandal, had never stopped its search for an adequate witness”. Here and throughout Tainted Witness, Gilmore refers to testimonial narrative as an animate force with its own agency. Any published text can be said to seek an audience, but Gilmore’s rhetorical choice underscores how testimony can have a life beyond the person who originally articulated it.

Gilmore plots what she calls “the memoir boom/lash” of the 1990s through a series of publishing scandals that also turned on women’s testimony. While memoirs of trauma and extremity were all the rage in the late 1980s and 1990s, Gilmore points to Kathryn Harrison’s The Kiss (1997) as the book that “blew up the memoir boom”. The Kiss describes Harrison’s four-year affair with her previously estranged father beginning when she was 21. Reviewers savaged Harrison with articles headlined “Dating Your Dad”, “Daddy’s Girl Cashes In” and “Pants on Fire!”. As Gilmore sees it, part of the outrage was spurred by the fact that Harrison was a gorgeous, successful writer: how could her story be credible if she wasn’t destroyed by telling it? After The Kiss, messy memoirs gave way to self-help and therapeutic narratives with happy endings. For Gilmore, Elizabeth Gilbert, the author of Eat Pray Love, is the queen of the redemptive, politically vacuous “neoliberal life narrative”.

If women are not trusted to tell their own stories unless they conform to a prescribed formula, is it any surprise that men should step in to do it for them? In Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin’s 2006 best-seller Three Cups of Tea, white, male Americans offer “proxy witness” on behalf of girls in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Five years after the book’s publication, major holes were punched in its story, but Mortenson weathered the scandal. The case shows, for Gilmore, that “the stigma of doubt attaches to testimony differentially based on gender, race, and nationality”. Men – especially white men – are more likely to be tolerated as unreliable narrators than women.

Strikingly, Gilmore extends her attention to female witnesses less sympathetic than Hill (Harrison is one; Monica Lewinsky might be another). She looks at the case of Nafissatou Diallo, the hotel maid who accused Dominique Strauss-Kahn, then head of the International Monetary Fund, of assaulting her in New York. While there was forensic evidence in her favour, Diallo lost her case in the criminal court in part because her claim to have been gang-raped earlier in Guinea was proved to be false. After Strauss-Kahn flew home to France, Diallo filed and won a civil case against him. Tainted Witness challenges us to stay focused on what is relevant to a particular case and to examine the biases that shape the way women’s testimony is adjudicated.

The tautological observation that women are thought to be untrustworthy because they are women invites speculation about its genesis. While a definitive answer lies outside the scope of Tainted Witness, Gilmore is especially astute when she shows how “bodies and story move in a choreography of testimony”. For example: “The instant Anita Hill saw a barrage of flashbulbs erupt the first time she altered position in her seat, she knew that in photographs of her testimony, her body could be made to tell a story that would compromise her.” These and other somatic moments in Tainted Witness show how profoundly female embodiment influences the reception of women’s words. If harassment and assault are a means of denigrating women’s power, might the charge of fabrication – in the sense of deceit – conceal an anxiety about fabrication in the sense of making or creating, and perhaps the most fundamental power of reproduction?

Now that America has elected as its president a man who denigrates women and their bodies, who thinks women who exercise their reproductive rights should be “punished” and who spouts xenophobic and racist views, Gilmore’s insights are more pressing than ever. Tainted Witness is an important and timely book. If ever we needed evidence that the work of feminism is not yet done, this is it.

Laura Frost is formerly associate professor of literary studies at Yale University and at The New School for Liberal Arts, New York City, and author of The Problem With Pleasure: Modernism and Its Discontents (2013) and Sex Drives: Fantasies of Fascism in Literary Modernism (2001).

Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say about Their Lives

By Leigh Gilmore

Columbia University Press, 240pp, £22.00

ISBN 9780231177146 and 1543446

Published 17 January 2017

The author

Leigh Gilmore, distinguished visiting professor of women’s and gender studies at Wellesley College, was born in Ohio, the second of four children.

“My father was a minister from South Bend, Indiana, and my mother a schoolteacher from Gulfport, Mississippi. We moved to a small town north of Spokane, Washington when I was 10 years old and I fell in love with the western landscape. We lived in a rural area. Some neighbors had cows and horses in their backyards and I never saw a dog with a collar, let alone on a leash. I was allowed to wander as far and as long as I liked. I am fairly sure that being allowed to find my own way served me well as a feminist scholar.”

She was, she recalls, “always a reader. The school library had one shelf of biographies and another of Nancy Drew, so I read my way happily through those. My parents bought a set of encyclopedias from a door-to-door salesman and I remember boring my family with my newfound knowledge gleaned from those volumes. My high school had a bookrack that was an endless source of fascination: The Angle of Repose, The Sound and the Fury, The Crying of Lot 49. I was an ecumenical reader, certainly, with an hour-long bus ride each way from home to school and no cellphone! I am not sure if I was studious so much as curious and with time on my hands.”

Gilmore’s undergraduate career was spent at the University of Oregon and the University of Washington, and she graduated from the latter. “I was eager for political engagement, for the vivacity I found in the theatre department, and for the kind of knowledge that had not been available to me previously: the study of Classics and the ancient world, Latin, drama, non-American history. Kind of a hodgepodge, but I found it compelling.”

Wellesley College, where she now lectures, remains a women-only institution, while many of the elite US institutions that were once female-only are now co-educational. Was more was lost or gained for women there?

Gilmore replies: “Although Vassar and Sarah Lawrence fit that bill, the top women’s colleges are thriving. Many of the women’s colleges that went co-ed did so for economic reasons, and each has its own story to tell about that decision. But I think the value of a women’s college is profound and not likely to change any time soon. Being educated in the company of women recalibrates the norm of who should lead, disrupts restricted notions of gender, and offers a reprieve from everyday sexism.”

Invited to mention the work of early career scholars that she found particularly valuable, Gilmore cites “Brittney Cooper’s work as a black feminist scholar and public intellectual [as] always relevant. Molly Pulda’s recent articles on life writing are attuned to the complexities of literary form and public reception. New work on hip hop and indigenous women from Jenell Navarro is timely and deeply thoughtful.”

Autobiography is a key theme in Gilmore’s work. Is the act of writing an autobiography, in whatever form, a liberating process? “Many women have said the experience of writing their life story is transformational. Some have said that in the process of writing about someone else – a husband or children – they found their own lives to be worthy of interest for the first time. That core experience of finding value and dignity in life and wanting to shape it in writing and share it with others is both profoundly personal and social.

“Writing an autobiography is a way for many women to claim public space, the space of mattering, to say, ‘I am here’. How and in what form that work takes place varies and is currently being explored, publically in social media and privately in therapy. Sometimes these fora are sufficient to the impulse of self-fashioning, but for some these represent steps toward writing a memoir. On the other side of this question, though, many women who publish life narratives are greeted with a level of doubt or outright disparagement that is independent of what they write. This is the phenomenon of doubting women that I write about in Tainted Witness.”

If she could change one thing about her institution, what would it be? Gilmore replies: “I wish that on election night, the campus community had been able to celebrate the victory of its most famous graduate, Hillary Clinton. That’s changing something other than the institution, though, isn’t it?”

What gives her hope?

“You pose that question after a bitter loss by an extraordinarily qualified woman candidate to a man with neither the judgement nor qualifications to be president, so hope is something very much on my mind. All of the young people who worked with such spirit and determination on Clinton’s campaign, the activists and community organisers in Black Lives Matter, the water protectors and the veterans who support them at Standing Rock, the conservatives who voted for Hillary, my students, my sons, and the persistent voices of feminism give me hope.”

Karen Shook

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: I believe you, 1,000 wouldn’t

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?