Since the Referendum outcome a series of leading political commentators have offered ideas of how to rebuild an obviously – and nearly equally divided – country.

Central to suggestions from both the Left and Right has been the rebuilding of vocational educational pathways to good-quality, skilled jobs – especially in those towns, cities and regions that have suffered most amidst waves of deindustrialisation, globalisation and economic restructuring. Vernon Bogdanor, Miranda Green and David Goodhart are just three commentators that have all recommended concerted investment in technical training to fuel both a new industrial strategy as well as the businesses and jobs that might underpin a series of new global trading deals.

But it is only Brexit that is the new part of this diagnosis. We have suffered from a gap in our education and training system for decades – perhaps even hundreds of years. We’ve always been rather better at "education" than "training". The extensive trailing of a new Industrial Strategy Green Paper puts an attempt to remedy this at centre stage.

As Vince Cable remarked in a speech too close to the end of his tenure as secretary of state at the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (neither he, his party nor his department are around to shape this version of industrial strategy), this is an issue that is part of the future for both further and higher education sectors. He describes an "upper technical" vacuum as a problem that lies across both sectors as well as in teaching and research.

"Our post-secondary education has become distorted. The OECD concluded that our post-secondary vocational sub-degree sector is small by international standards – probably well under 10 per cent of the youth cohort, compared to a third of young people elsewhere. In the US, more than 20 per cent of the workforce have a post-secondary certificate or an associate degree as their highest qualification. In Austria and Germany, sub-degree provision accounts for around 50 per cent of the cohort. In South Korea, one third of the youth cohort enters junior college on two-year programmes of higher vocational training. Elsewhere, countries with low volumes have sought to address the problem. Sweden, for example, trebled its numbers in higher VET programmes between 2001 and 2011."

As yesterday’s Sunday Times says, the reform of technical education has not been without previous attempts or good intentions from government. From Samuelson and Forster in the 19th century, Butler, Robbins and Crosland in the 20th and Leitch and Sainsbury in the 21st, we haven’t been short of recommendations or new institutional solutions.

Crosland’s answer was the polytechnic. Before that it had been colleges of advanced technology. In the later years of New Labour it was centres of vocational excellence and then national skills academies. Vince Cable offered both national colleges and catapult centres for applying technical research. The coalition ended and David Cameron’s brief honeymoon saw the taking up of Labour’s ideas of institutes of technical excellence and technical degrees into institutes of technology.

So this is a long standing issue with a long history of policy failures in both the distant as well as the more recent past. In many ways, more recent reforms – especially to funding – have seen the homogenising of HE and FE around younger full-time learners. In both sectors, the numbers of part time and older learners have fallen dramatically over the past decade alongside those of any age learning or training in the workplace.

What then could an institute of technology look like if it’s not to go the way of previous initiatives? To my mind there are six key issues that stand out and will help to define what they are, why they matter and where they fit in the existing landscape of institutions, sectors and systems.

1. Identify the primary purpose and stick to it

If the objective is to help drive an active industrial strategy, then the overriding purpose will be to drive economic growth in key sectors. It follows therefore that they are likely to be specialist in focus and in places where there are concentrations of the types of firms that have the potential to grow and to boost both productivity and jobs.

This focus will be diluted if other functions are built in. There are lots of things that governments might like new institutions to achieve – reconnecting places, providing competition in HE, rebranding the best of FE – but even if all of these are desirable, they will make the primary purpose harder to achieve. Mission creep should be avoided.

2. Make clear that institutes of technology don’t ‘belong’ exclusively to either FE or HE sectors

This is important to answer not least because there are currently bills before Parliament intending to dramatically reform both. There is an explicit aim for new providers in both sectors to increase competition and spur innovation. If that is what ministers want, then they should think about introducing some new clauses to one or both bills pretty quickly.

But the potential for ambiguity is a problem. When Labour and the Conservatives first considered the idea, it was seen as way of incentivising and recognising (and rebranding) the best in the FE sector. That’s been tried before with CoVEs, NSAs and national colleges. More recently, Dyson has received government backing to open an institute of technology primarily as a new challenger institution amidst the increasingly competitive landscape of HE.

Neither is it sensible to describe these institutions as for those who don’t go to university. To be most effective in their support for industries, institutes of technology will have to offer a range of skills to a range of people. So these are all soundbites that are best avoided.

The better answer is to establish the function and then to let the institutional form follow. As we have seen in point 1, that function is economic growth supported through higher level technical learning. Given our history, it doesn’t seem that institutions in either sector would be able to drive this on their own.

3. Be clear and consistent about the role of employers

Institutes of technology – like colleges or universities – can’t deliver growth by themselves. They should not be a supply-side-only model and employers should be more than just passive beneficiaries of their outputs. Employer investment and involvement will be critical. This cannot be abstract or expressed only in the eventual recruitment of graduates or products and services. Incentives for partnership and investment need to be at the heart of new institutes and their governance and/or ownership should reflect this too.

Essentially, they should aim to bring together the supply and demand sides; public and private; HE and FE and employers into an organisational form that can bring the best and most appropriate actors together into institutions that work and add value. Collaboration and progression between FE and HE must then be central.

4. Learn from models that work (and understand why)

I can think of two or three models that might be useful. One is the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) near Sheffield. This is a lesson in itself because policy didn’t create the whole thing, rather it offered a series of initiatives including national colleges, catapult centres, research partnership investment funding and enterprise zones – and revenue funding for apprenticeships and research. Led by Sheffield University, it includes major employers such as Boeing and Rolls Royce.

A second model is less specific about form and offers competitive challenge funding for partnerships to come together. This might look like Innovate UK funding platforms (or RPIF) – for innovative funding proposals to develop new institutes. Or it might look like the competition that the mayor of New York ran in order to develop a new technical campus on Roosevelt Island.

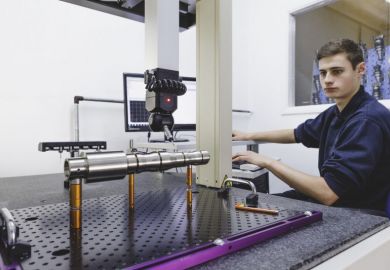

The best international technical models seem to do more than provide training. Applied research capabilities are also a major feature, through which individuals and firms can also learn, test and refine new ideas. Catapult centres have been England’s response to the Hauser and Dyson reviews and applied research was also an essential part of the vision for CATs and polytechnics in the past.

But the AMRC is just one model in one sector. Other sectors have different needs and are likely to look quite different. It is difficult, for example, to think of what an institute of technology for the digital or creative industries might look like. But putting sufficient funding and flexibility on the table to enable employers, colleges and universities to apply their expertise would seem a good idea.

After all no one organisation – not even government – has all the best answers. So whatever models are preferred there needs to be sufficient flexibility across sectors and places for partnerships to come together and to create the appropriate mix of capabilities. Officials in the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for Education must not therefore be too prescriptive.

5. Decide what qualifications matter and give institutes of technology autonomy to create their own

Foundation and honours degrees may be sufficient. Or they may not be. Apprenticeships may be the best vehicle. But they may not be either. These institutions with employers at their heart must be empowered to decide. Vince Cable was right when he set out his plan for national colleges, that they should have both the autonomy and expertise to develop their own qualifications rather then depending on either exam boards or universities for accreditation.

6. Locate institutes of technology in places that will give them the best chance of working

If the economy is to grow and the economic gaps between regions within England addressed, then geography must be a factor. But again we must be wary of trying to cure too many ills with one type of institution. Institutes of technology should prioritise growth within an active industrial strategy and by doing so they will have a better chance of succeeding if they are close to clusters, firms, transport and so forth as well as to collaborating institutions such as universities and catapult centres. Some towns and cities simply won’t have the combination of such assets. We can’t afford to be too sentimental or to expect new institutions to achieve too much. Others haven’t.

The problems of low skills and poor jobs and wages still need solutions, of course, and FE and HE must play their part, but that doesn’t mean they should open in either the most deprived or most disconnected areas. As with other issues, the key lesson is to set clear objectives and to ruthlessly stick to them.

If the industrial strategy is to have any chance of working, then firms in key growth sectors and clusters will need the right skills and knowledge. They will also need the latest technology and the right support to apply research, refine products and services and to grow. If institutes of technology can deliver on these issues, they will be doing something that our FE me HE systems have struggled to do for many years. That is why they matter.

So that is the "why", the "what" and the "how" to make institutes of technology work. It probably means that there won’t be very many – at least not in the first instance. But being precise – or ruthless – about sector, place, make up and mission will give them the best chance of succeeding.

Andy Westwood is director of the University Observatory and a professor in FE and HE at the University of Wolverhampton. This post originally appeared on his own blog.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login