‘True is it that we have seen better days’

Disciplines are the price society pays for our culture to be passed on to the next generation. So argued the French historian André Chervel, reminding us that the intergenerational transmission of culture is what keeps societies together. When I began as a lecturer in French in the 1970s, that culture was made up of literature and philosophy. I was entranced by the bittersweet of Charles Baudelaire’s invitation to a journey and the dark cool of Jean-Paul Sartre’s dissection of human existence. Modern language studies have changed a good deal since then, as cultures have changed, and I could not have predicted that I would one day take satisfaction from teaching bandes dessinées (comics) or researching the tense debates around laïcité (secularism).

New disciplines are born as knowledge expands, but what are the costs of losing a discipline? This is a serious question as the UK faces a continuing decline in modern languages. Recent trends are not promising. According to figures from Ucas (the body responsible for higher education applications), the number of universities offering language degrees in the UK is now 30 per cent fewer than in 2000. Two or three language departments have been closing every year. Surprisingly, for most of this time the number of students actually doing these degrees remained fairly stable, but concentrated in fewer institutions: mostly the more prestigious ones. Now, the actual numbers of students are dropping in response to the collapse of languages in the upper years of secondary school, hitting even the more popular departments.

So why do we need to study foreign languages and cultures? The answer used to be straightforward. Modern languages emerged as a discipline in the UK in the late 19th century, to enable elites to know more about their powerful neighbours and imperial competitors: principally France and Germany, but also Italy, Spain and Russia. Initially, the model of Classics was followed: hence the focus on literature and philosophy. But this focus also served a practical purpose since the relevant texts exemplified sophisticated writing, were conveniently available in the portable form of books and reflected the general culture of the elites in their authors’ countries.

Search our database for languages jobs

More recently, degrees have included the social and political studies that can help us to understand the wars and revolutions of the 20th century, and the new political and economic relations they provoked. Other forms of cultural study came later, focused on more popular genres, such as cinema and even comic books.

The boom years for language degrees in the UK were the mid-1990s, driven by a wave of enthusiasm for the European single market, which was launched at the beginning of 1993. Since then, the popularity of language degrees has more or less tracked the level of public enthusiasm for the European project. But, despite the current uncertainties surrounding the future path that the UK will take post-Brexit, it still needs people with these degrees. And government agencies have often identified languages as strategically important – with a central role to play in business and diplomacy, and in addressing issues of migration, security and social cohesion – and so worthy of extra support.

Today’s language departments largely focus on providing an attractive diet of studies for potential students. In a student-centred system, there is no alternative.

So what do students want? Their wishes are very varied. Some are still entranced by the high culture of their near neighbours. Some want to focus more on acquiring fluency in the relevant language – and, increasingly, in more than one language. Some are fascinated by how language works as a system or as a social activity. And some want to know more about the countries that speak their chosen language, often with an eye to future career prospects.

Institutions have responded to all these different needs, sometimes by twisting academics’ arms to offer courses more likely to appeal to their children’s generation, and often by offering combined degrees. For some years, single honours degrees in one language have been a minority taste. Ucas figures for 2015 show that they are chosen by only about one in 10 languages students. Almost as many students opt to study two or more languages together. The remaining eight out of 10 combine a language with another subject. Humanities are the most popular choice (English, history, philosophy), but social sciences, especially business studies, are also widely chosen. A significant number of students also choose a language as part of a degree with maths, physics, engineering or another natural science.

With so many links to other subject areas, language degrees look in many different directions. They all offer language learning to the highest level and support an increasingly diverse range of linguistic, cultural and social studies – although only the largest departments can hope to cover all areas. This is the new shape of the discipline nationally. But it will need to maintain a critical mass of core students and researchers if it is to survive.

The price for academics will be to find ways of inspiring students who are more familiar with the Baudelaire family of children’s author Lemony Snicket than with the author of Les Fleurs du mal.

Michael Kelly is emeritus professor of French at the University of Southampton.

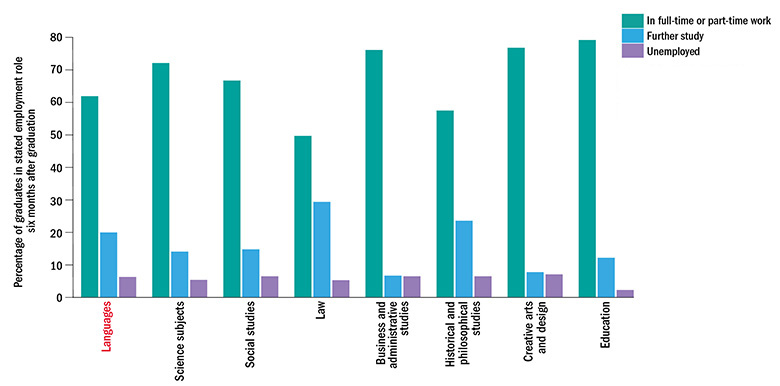

Employability of UK languages graduates

‘Something is rotten in the state of Denmark’

Until recently, language studies in Denmark were supported throughout the educational system.

At the beginning of the 21st century, 40 per cent of pupils left secondary school with a good basic knowledge of three foreign languages: typically English, German and French or Spanish. Degrees in those languages were offered at all universities with humanities programmes, and Italian and Russian were also commonly on offer.

Yet a reform of secondary schools in 2005, partly designed to strengthen the natural sciences, removed the obligation to offer pupils a third language, and many chose not to study more than the two compulsory foreign languages. This changed the situation dramatically and, today, only 4 per cent of pupils graduate from secondary school with three foreign languages. This has led to increased difficulties in recruiting students for modern language courses at universities. The consequences can be measured in the statistics. Between 2005 and 2016, according to articles in the Danish press, more than 35 language programmes – or just under half the total number – were closed. This has reduced the number of courses in major European languages, such as French and Italian, and led to closures in more minor ones, such as Dutch and Finnish.

At the organisational level, language departments have been closed or merged. The University of Copenhagen now has just a single department of modern languages (teaching English, German and Romance languages) and another offering language-based area studies focusing on parts of the world outside Western Europe and North America. At Aarhus University, the major European languages have been merged into a School of Culture and Communication, which also includes disciplines such as musicology, media studies, Scandinavian studies, art history, digital design and comparative literature.

These developments have been caused in part by a series of reforms aimed at making universities strategic players in the global marketplace for education. This has encouraged competition between national universities for research and teaching funding. Money for teaching is allocated on the basis of student activity, measured in terms of exams passed. Small programmes are inevitably regarded as loss-making activities, and so are the first to be closed when funding goes down.

A task force was established in 2011 by the Danish government to address the malaise. This led to a report, Languages are the Key to the World, offering a coherent strategy for how Denmark could strengthen its foreign language education. Unfortunately, however, the centre-left government that came to power in 2011 only implemented some selected recommendations and adopted other policies that proved highly damaging. The most significant was the so-called dimensioning plan, which requires university programmes with above-average unemployment levels to reduce their student intake by up to 30 per cent. The plan, based on data from 2002-11, hit language courses very hard and, as funding depends on the number of exams passed, in effect amounted to an austerity programme.

To complete the misery, in 2015, the government imposed significant year-on-year cuts on the entire education sector. These have resulted in a new wave of language programme closures so severe that the ministries for education and higher education are now working on a national strategy to counter it. This is due to be made public in the spring, but it is still unclear what its objectives are. Public statements have put an almost exclusive stress on harmonising education with the needs of the labour market, whereas more normative questions about the role of modern languages – their importance for diplomacy, security, defence, intercultural encounters and social cohesion – have not been raised.

Universities have responded to the mood music in various ways. Aarhus has recently established a degree programme in intercultural studies, in English and another language (German, French or Spanish). Copenhagen has joined forces with Copenhagen Business School to set up a master’s in intercultural market studies, combining courses in subjects such as organisational theory and stakeholder relations with German, French or Spanish. Both degrees combine market-oriented skills with insights into languages and cultures.

But we should be concerned about a purely instrumental view of modern languages that plays up advanced skills training at the expense of supporting a research-led discipline where literature, culture and history are investigated through the relevant languages. Recent developments actually tend to undermine public perceptions of modern languages as legitimate areas of serious academic enquiry. Those of us working in the field need to make it a top priority to be more forceful in communicating to the wider public the value of language and culture studies.

Lisbeth Verstraete-Hansen is an associate professor in French and francophone studies at the University of Copenhagen.

‘The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose’

Donald Trump’s aggressive isolationism is likely to have chaotic effects on modern languages departments in the US. It is tempting to presume that student numbers will fall, but the Trump era is just as likely to draw undergraduate students into the study of foreign languages and cultures. Either way, US modern language departments in 2017 are in stronger health than popular media narratives would have you believe.

It is often insinuated that modern languages are a drag on the solvency and adaptability of the public university. But this is simply not true. At my home institution, the University of Arizona, modern languages programmes rank in the top 20 per cent of revenue-generating units campus-wide. Nationwide, there was a 6.7 per cent dip in foreign languages enrolment between 2009 and 2013 – a decline that outstripped the overall fall in student numbers in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Yet ambitious recruitment efforts at first-year student orientation events and large general education “feeder” courses have enabled us to buck the trend and continue to coax upwards enrolment of majors in French, German, Russian, Italian, Chinese and Japanese. And this is without the large private-sector subventions often required in other disciplines.

Those disciplines across campus – medicine, business, manufacturing, agriculture – may address language and culture instrumentally, as a necessary component of “getting to yes” or “closing the deal”, but they rarely have space in their curricula to enquire about the complexity of multilingualism and translation in any sustained fashion. Modern languages curricula at Arizona, in contrast, offer courses grounded in the lived complexity of societal multilingualism. They apply linguistic, cultural, historical and literary approaches to questions relevant to engineering, business or even arid lands management. Our course on “German culture, science and technology”, for instance, shows how the specific traditions housed in the German language offer a meaningfully different set of operational principles and assumptions about things such as “security”, “risk”, “progress”, “growth” and “the economy”. Students come away with a much stronger sense of how non-governmental organisations can better acknowledge the belief systems of their beneficiaries in their home languages; how physicians and nurses can engage in nuanced conversations with seriously ill people that truly relieve suffering; and how focus-group-tested political rhetoric is often designed to hide structural inequalities in society.

These outward-facing modern languages curricula are often best suited for dual-degree courses, and most professors I know urge undergraduates to concentrate on a language alongside another major. But instead of just training them in how to “get ahead”, recent modern languages programmes show students how to notice when powerful interests are aiming to manipulate them with coercive language, imagery and marketing, and how to transform that moment of noticing into resources for creativity, justice and collaboration.

The major challenge of the next 10 years will be continuing to build this critically engaged, applied and outward-facing momentum in modern languages curricula. Threats continue to hack away at our resources, and the Trump-occupied White House has removed all multilingual content from its website, reminding us that English-only is a powerfully resurgent delusion.

David Gramling is assistant professor in German studies at the University of Arizona.

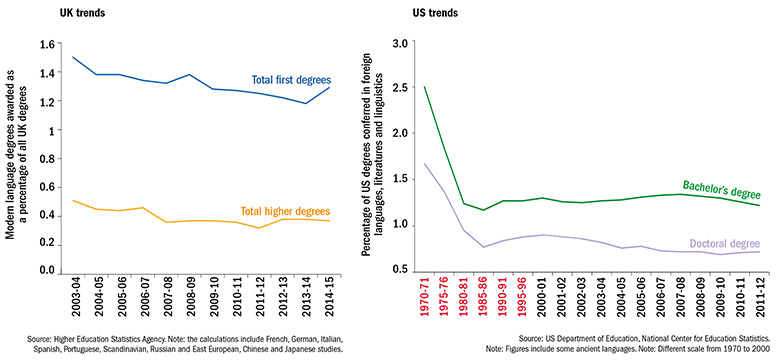

UK and US trends in percentage of degrees awarded in modern and foreign languages, literatures and linguistics

‘It is not in the stars to hold our destiny but in ourselves’

Modern languages in the UK have been the perennial subject of articles depicting gloom and predicting doom. The vote to leave the European Union is likely only to darken the mood further. So why, you might ask, would any early career academic commit their future to a discipline in such apparent decline?

I am an optimist by nature, but that optimism is not blind. Concrete things are being done to revive the fortunes of modern languages in the UK, and I am confident that these will lead to increased student numbers within a decade.

There is no denying the recent decline. According to Claire Gorrara, professor of French studies at Cardiff University, the number of UK school students taking at least one modern language to age 16 has declined from 55 per cent in 1995 to approximately 22 per cent in 2013. Particularly significant in that decline was the Labour government’s decision in 2002 to remove modern foreign languages from the list of compulsory subjects for the GCSE examinations taken by most 16-year-olds. This has had an inevitable impact on the pipeline of school-leavers wanting to study languages at university.

But modern linguists have been fighting back. Their efforts centre around a nationwide series of programmes known as Routes into Languages, which aim at encouraging more schoolchildren to take up languages.

One example is Nottingham Trent University’s Bespoke GCSE Language Programme, which counters the perception that the study of modern languages is for only privileged students in “elite” universities. Begun in 2008, it has led to a 95 per cent increase in the uptake of GCSEs in French and German at participating schools. It has also had an impact on university recruitment, with Nottingham Trent seeing a 61 per cent rise in the number of students on its modern language courses between 2008 and 2014. The university recently introduced an equivalent programme aimed at the A-level school-leavers’ exam, which could boost that trend yet further.

Gorrara herself has set up a project that involves modern language students from four Welsh universities visiting 28 local schools in an attempt to drum up interest in their subject. The students have discovered that school pupils lack confidence in their speaking ability and do not regard language learning as necessary for employment prospects – a view that tends to be supported by their immediate social circle. Again, the intervention proved successful, as demonstrated by an increased uptake of GCSE languages at participating schools.

Other programmes have employed imaginative schemes to highlight that language-learning can be fun. The North East Routes into Languages Consortium recently held The Great Languages Bake Off, where pupils were filmed cooking foreign dishes and narrating it in a language that they were learning. And the Language Factor Song Competition encouraged young people to sing in a foreign language. The success of such schemes is further attested to by a 2014 study that found that three-quarters of first-year language students who had participated in one affirmed that it had improved their perceptions of languages. That was especially the case among students from low-achieving schools.

The growing popularity of joint degrees also demonstrates that the message about the value of languages to all sorts of professional careers is slowly getting through. The same is true, of course, regarding academic careers – which is why the University of Birmingham recently launched the UK’s first one-year instruction course for researchers who need to acquire a reading ability in a particular language.

Further good news is afforded by the fact that modern languages will be included in the English Baccalaureate: the list of GCSE-level subjects that will form the basis of English school league tables from 2020.

So while the challenges remain significant, I am confident that the value of modern languages will increasingly be recognised by young people – who, despite Brexit, will find themselves living and working in an ever more globalised world.

Lorraine Ryan is a “Birmingham fellow” – a research-focused lecturer – in Hispanic studies at the University of Birmingham.

‘They have been at a great feast of languages’

There has been a sense in Australia for many years that modern languages are in something of a crisis. My own experience in French studies at the University of Melbourne reflects both the upheavals and breakthroughs that modern languages have faced since 2000. When I began teaching the advanced French core programme, there were about 100 students. This cohort has now doubled in size. Elective subjects in French have leaped from 30 to 90 students. But these striking statistics do not tell the whole story of languages’ journey either at the University of Melbourne or in the Australian context.

As long ago as 2007, the Group of Eight coalition of research-intensive universities released a document titled: Languages in Crisis: A Rescue Plan for Australia. The fact that they felt the need to present such a plan underscored the government’s lack of leadership in responding to the dramatic decline in secondary school students graduating with a second language – from 40 per cent in the 1960s to 13 per cent in 2007. The report also revealed that the number of languages offered in Australian universities had declined from 66 10 years earlier to just 29, with nine of those offered at only one institution.

In response, language departments formed the Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities (LCNAU) in 2011, to engage with the government and others on protecting language programmes. Initially funded by the Australian government, it now relies mainly on membership and sector sponsorship, but continues to have a big impact. It has established, for example, the University Languages Portal Australia, which enables students to identify which universities teach certain languages, and to what level. And it has orchestrated a number of prominent media campaigns to protect language departments under threat, with some success.

There have been other efforts to streamline the delivery of language learning in Australian universities. In 2008, the Brisbane Universities Language Alliance garnered more than A$2 million (£1.2 million) of federal funding to consolidate the languages taught at the three Brisbane-based universities, offering only Mandarin Chinese across all three, Japanese and Spanish in two, and seven other languages at only one site. These collaborative arrangements have allowed some threatened languages to survive.

Meanwhile, the University of Melbourne introduced its new “Melbourne Model” (now known as the Melbourne Curriculum) undergraduate programme in 2008, which obliges most students to take 25 per cent of their bachelor’s degree in “breadth” subjects – that is, subjects outside their home faculty. Enrolment in languages has surged, in some cases doubling. There has also been increased interest in Melbourne’s diploma in languages, studied alongside a bachelor’s or postgraduate degree in another subject. The Melbourne Model has since been replicated at the universities of Western Australia – where languages have had particular success as students in their home arts faculty are also allowed to take them as “breadth” – and New South Wales, and is soon to be implemented at the University of Sydney.

Even at universities still using a traditional curriculum, Australian students are not required to commit to an entire undergraduate degree in languages and normally take them as a major in an arts degree. Consequently, the languages with the largest enrolments (French, Japanese and Mandarin) may have more than 1,000 students at the universities of Melbourne, Sydney, Queensland and the Australian National University. The last still offers 28 different languages, ancient and modern, while all research-intensive universities offer at least the “big seven”: French, German, Italian, Spanish, Japanese, Mandarin and Indonesian.

Postgraduate student numbers fluctuate according to unemployment statistics and scholarship availability, but attrition rates from undergraduate to postgraduate levels are high – an obvious result of less specialisation. However, this does not necessarily pose longer-term problems for the sustainability of the disciplines, since there is robust competition for academic positions in most languages.

And although undergraduate numbers peaked in 2010, they still represent a considerable increase on the pre-2008 numbers. Nothing can be taken for granted, however. Australian society remains pervasively monolingual. There is no automatic acceptance of the value of second-language learning, even within the most prestigious universities. And the University of Canberra closed all its language programmes at the end of 2013.

I consider myself fortunate to still be teaching so many talented students in the advanced French core programme, and my French electives survived the Melbourne Model and our language curriculum reform. But, in addition, I am also coordinating and teaching interdisciplinary subjects on wines of the world, a taste of Europe (about European food), and a flagship subject for incoming and outgoing exchange and study abroad students called Going Places – Travelling Smarter. Modern languages will survive if academics continue to work together to support each other across languages and are flexible enough to respond to the demand that exists for more diverse language pathways. Meeting that demand will increase students’ cultural mobility and present them with intellectually rewarding challenges both at home and abroad.

Jacqueline Dutton is associate professor of French studies at the University of Melbourne.

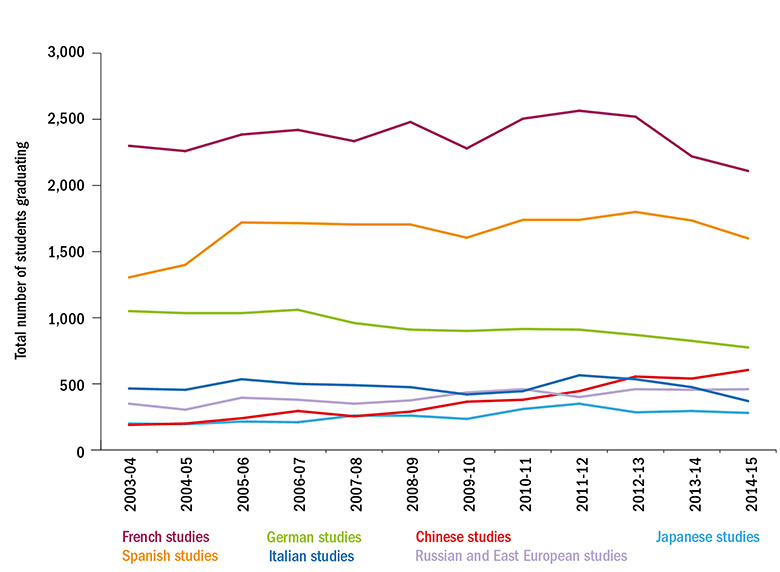

UK trends in specific languages

‘Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety’

The disciplinary assumptions of the modern languages that I discovered as an undergraduate in the late 1980s were clear ones. They were firmly mapped on to the boundaries of a nation state (in my case, France), linked closely to canonical literature and associated with aspirations to linguistic competence in a single language.

I spent two years in Brittany and witnessed there at first hand centralised French language policies at a sub-national level. It was as a doctoral student, however, working on questions of exoticism and travel writing, that I began to explore more fully the monolingual and monocultural underpinnings of modern languages. I discovered a wider Francosphere in which French was not only spoken and written differently, but was also in permanent contact with other languages and cultures. The shifts this has allowed would have been unimaginable to my undergraduate self. My research and teaching now complement literature with a range of other media (including comics and material heritage), and are actively framed by transnational, as opposed to national, considerations. I am able to study phenomena as varied as multilingualism in France itself, human zoos, the Haitian Revolution and the penal colonies of Australia, French Guiana and New Caledonia.

My own story as a teacher and researcher reflects the ways in which the UK research landscape in modern languages has evolved dramatically, especially over the past decade.

One of the spurs was largely accidental. Instead of the five language-specific subpanels employed by the 2008 research assessment exercise, the 2014 research excellence framework relied on a single “unit of assessment”. This gave modern linguists a timely opportunity to turn their historical fragmentation along linguistic lines into a lively conversation about the renewal of disciplinary coherence and purpose – now evident in a proliferation of stimulating new projects.

Those linked to the major “Open World Research Initiative”, recently launched by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, are actively underlining the strategic value of languages in policy areas, especially relating to the linguistic superdiversity of the UK. They are also addressing how we translate often complex research into forms appropriate for wider audiences. Exemplary in this regard is the new pop-up Museum of Languages, planned by the Cambridge-based project “Multilingualism – Empowering Individuals, Transforming Societies” and scheduled to appear in shops on the high street in Belfast, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Nottingham, as well as online.

Researchers are also demonstrating how modern languages increasingly help us understand our own culture. For instance, a consortium of modern linguists from universities across Wales led by Bangor University has recently run a project examining the ways Europeans portrayed Wales and “Welshness” in travel writing since 1750. The group is now exploring the implications of the findings for the modern tourist industry.

The AHRC’s “Translating Cultures” theme, which I have been leading since 2012, encompasses work from across the arts and humanities, but includes many language-based projects that reveal the possibilities of breaking down barriers between traditional language fields, engaging with so-called community and heritage languages, and opening up to other disciplinary fields.

One of the large grants has gone to a project called “Transnationalizing Modern Languages”. This looks beyond the national frames to which our discipline is often limited, and studies diasporic communities around the globe to offer insights into how people respond to living in bilingual or multilingual environments. And a project based at the University of Nottingham is exploring contemporary relations between China and Africa through a focus on soft power, cultural exchange and translation.

Finally, research in modern languages has an increasingly important role to play in holding to account both those working in other disciplines and those formulating policies that claim international reach while remaining linguistically silent. A powerful example is “The Listening Zones of NGOs”, a project based at the University of Reading that is working with humanitarian organisations to raise the profile of languages and cultural knowledge in development and international relations.

What Mary Louise Pratt, the celebrated American theorist of languages and cultures, usefully called “knowing languages and knowing the world through languages” is no longer seen as an appendage to major research initiatives driven by other disciplinary fields. Research in modern languages is increasingly proving itself to be intellectually vibrant, positioned at the forefront of the arts and humanities, and – perhaps most significant – capable of playing a crucial role in society at a time of national uncertainty.

Charles Forsdick is James Barrow professor of French at the University of Liverpool.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login