An analysis of authorship data from journal papers across several subjects and countries has given a wide view of what progress has been made on gender equality for researchers over the past 20 years.

Gender in the Global Research Landscape, produced by Elsevier, mines data from the journal publisher’s Scopus database – containing 62 million documents published in more than 21,500 titles – to compare the gender mix of researchers across two inclusive five-year time periods: 1996 to 2000 and 2011 to 2015.

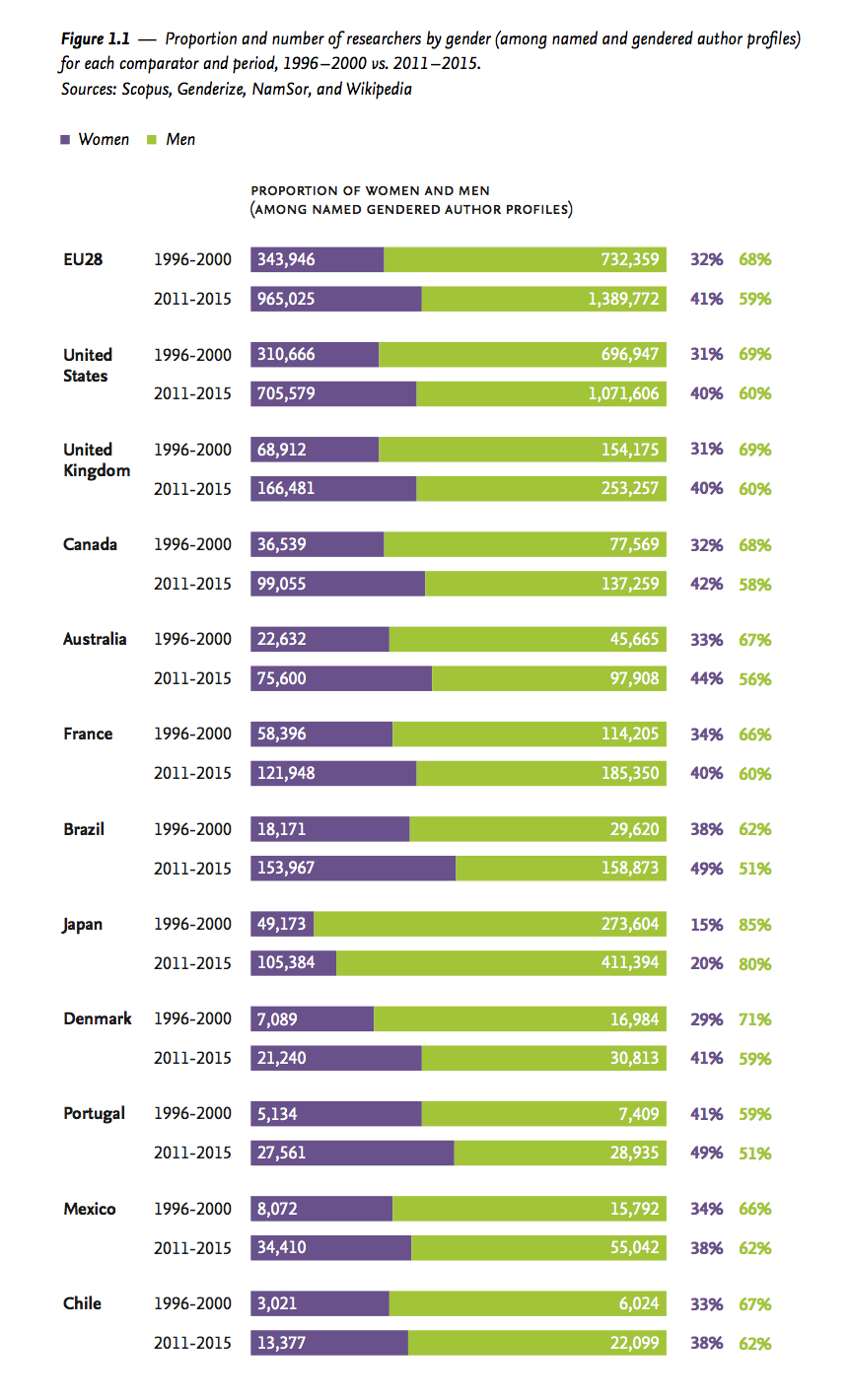

To produce its results, the analysis used a complex method of identifying, where it could, the gender of research authors in the database. Although this approach limited the number of countries included in the analysis to those where gender could be most accurately attributed to authors, a key overall finding was that, across the globe, the proportion of female researchers has increased over the time periods (see chart below).

Some nations fare much better than others: in both Brazil and Portugal, for instance, the proportion of women among author profiles was 49 per cent from 2011 to 2015 (up from 38 and 41 per cent, respectively, from 1996 to 2000). However, in Japan, although the proportion of women improved over the time periods, it was still just 20 per cent from 2011 to 2015. The country with the largest percentage point increase in the female proportion between the two time frames was Denmark (moving from 29 per cent to 41 per cent).

When looking across subject areas, the picture becomes much more mixed. Fields that are well known for having difficulties with gender equality in research do perform poorly, although again improvements can be seen over time.

For instance, according to the report, in the physical science subject areas of computer science, energy, engineering, maths, and physics and astronomy, “the majority of comparator countries and regions [had] fewer than 25 per cent of women among researchers” from 2011 to 2015, despite often improving from a very low base. This compares with subject areas such as biochemistry and medicine, where most of the countries analysed now show at least a 40 per cent proportion for women, and nursing, where the percentage is up above 60 per cent for some nations.

On research output, the report shows that, in general, female researchers publish less than men – something that has been identified elsewhere and has been attributed to different working patterns between the sexes such as career breaks for family reasons. However, another key conclusion from the Scopus analysis is that when the citation of research – normalised for subject area and other factors to produce a field-weighted citation impact (FWCI) – is analysed, there is no significant difference between men and women. Although men tend to have a slightly higher FWCI overall, women’s FWCI is higher in the US and, in the UK and the European Union, it is about equal (see chart below).

The report also looked at the number of times that research is downloaded. This showed values that tended to be higher for women than for men although again, like FWCI, the differences were small.

According to Lesley Thompson, director of academic and government strategic alliances at Elsevier, the relative parity between men and women on these measures – as opposed to the differences in research output – was an important finding.

“I think what this report does is it gives a very firm evidence base that females and males are equally cited,” she told Times Higher Education. “The reasons behind why one gender produces fewer papers than the other is a very deep question, and I think [that] further research is needed on that.

“But anybody looking at recruitment of males or females should be reassured by this evidence that both produce high-quality work of similar standards, and that is important.”

Dr Thompson, a former programme director at the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), said that the report could also be a useful evidence tool for countries to improve gender equality in subjects that have traditionally struggled, such as the physical sciences, by looking at how other nations were doing. In particular, she pointed to places such as Brazil (where the proportion of female researchers publishing in engineering, for instance, jumped from 16 per cent to 29 per cent over the two time periods).

“I personally would like to understand what is happening in Portugal and Brazil…compared to what is happening in northern Europe,” she said.

“That then opens up the chances of having a discussion to learn from each other and take things forward beyond saying…women are [just] not represented very well [in these subjects].”

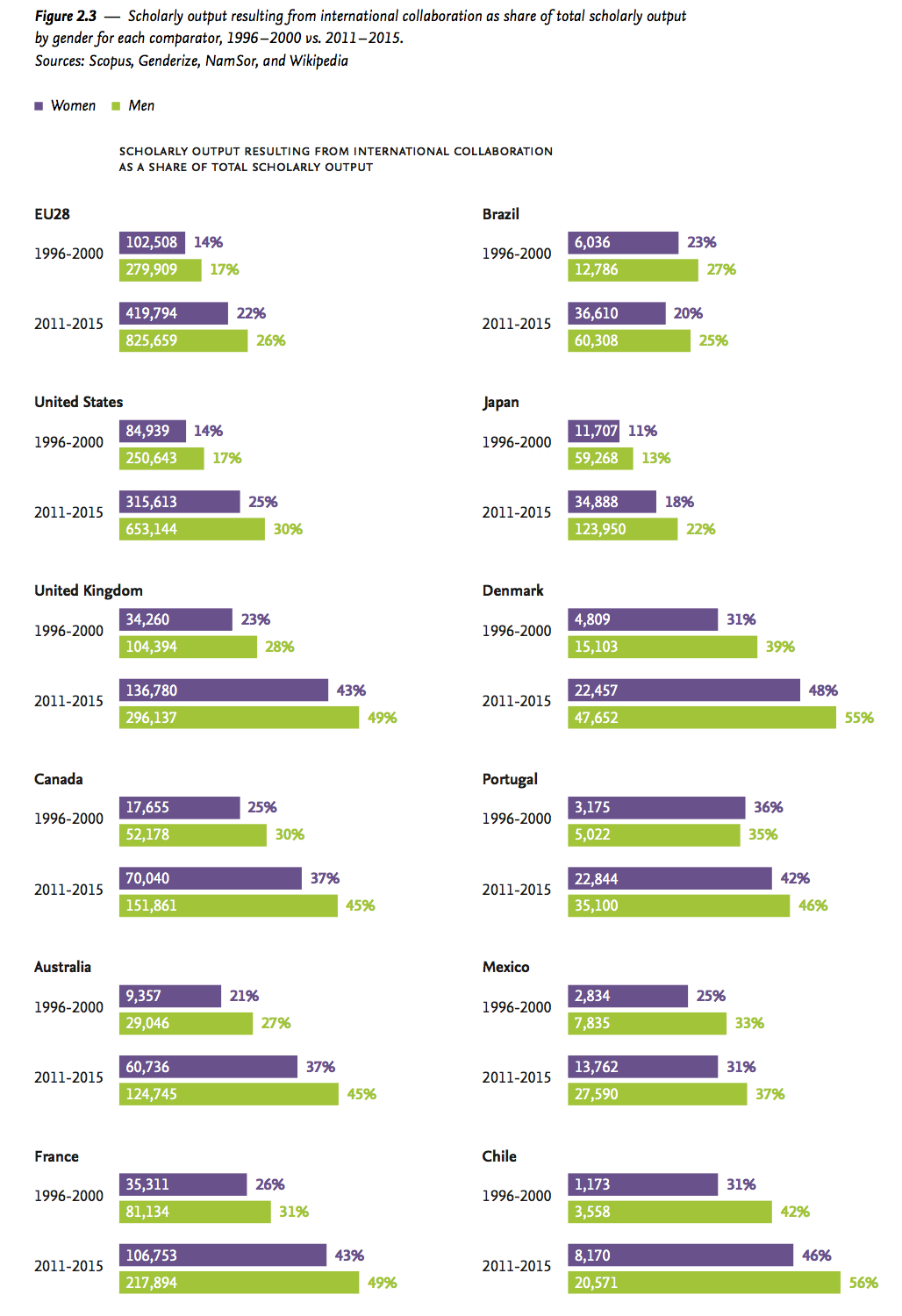

Elsewhere in the report, there is evidence, as other studies have found, that women are less likely to collaborate internationally on research papers, despite the clear trend over time towards more academics working together across borders (see chart).

However, the report also notes that this difference between men and women does not seem to have affected the quality indicators such as FWCI, something it calls “unexpected” given that there is evidence that international collaboration improves citation impact.

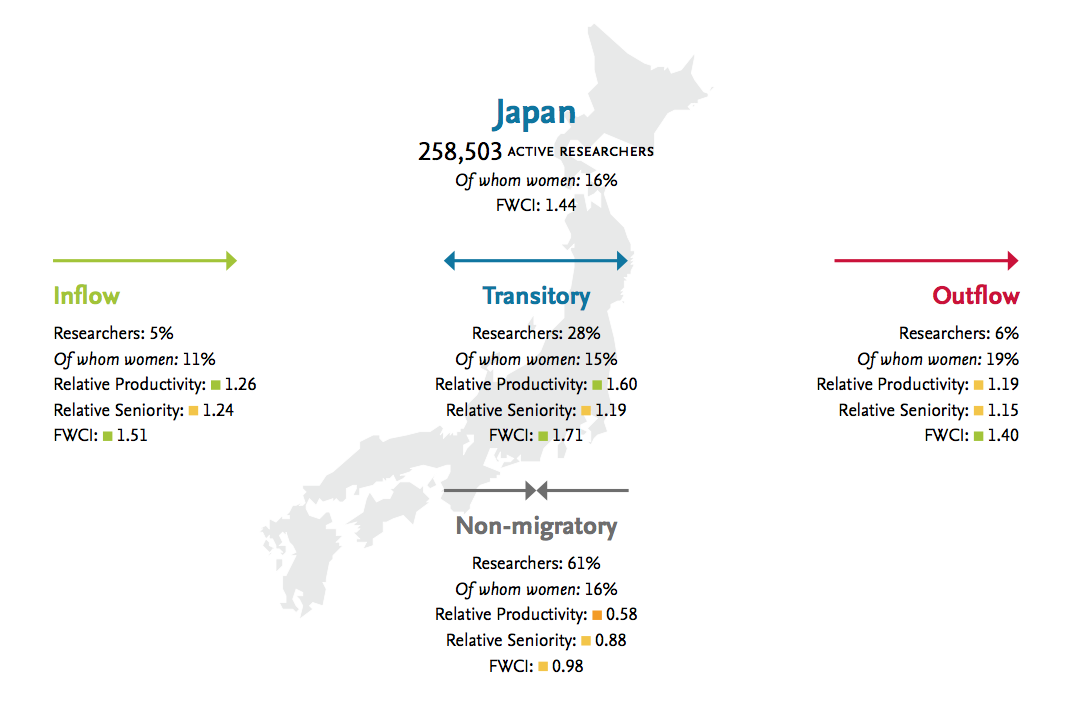

The study also suggests that the gender difference on international collaboration could be linked to women being less likely to be internationally mobile: the report contains figures showing that, in the UK, Canada and Brazil, the share of researchers who do not migrate across borders who are female is lower than the share of female researchers overall. Meanwhile, Japan provides a very interesting case study on international mobility: the share of researchers leaving the country who are women is much higher than the share of women who stay put (see below).

A whole host of other indicators are analysed in the study, including collaboration between academic researchers and industry (women are slightly less likely to collaborate); highly interdisciplinary research (women’s scholarly output contains a slightly larger proportion of such research); and, using statistics beyond Scopus, the proportion of women among researchers filing patents, a figure that is under 20 per cent for most countries. Rachel Herbert, a senior market intelligence manager at Elsevier and one of the report’s authors, suggested that this could be down to the majority of patents being filed in fields such as the physical sciences.

The study also carries a whole section on research into gender as a topic – such research is growing faster than scholarly literature generally. It is also becoming less concentrated in the US (50 per cent of papers in 1996 to 2000) and more equitably split between the US (34 per cent of papers in 2011 to 2015) and the EU (35 per cent in 2011 to 2015).

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Women in research advance steadily

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login