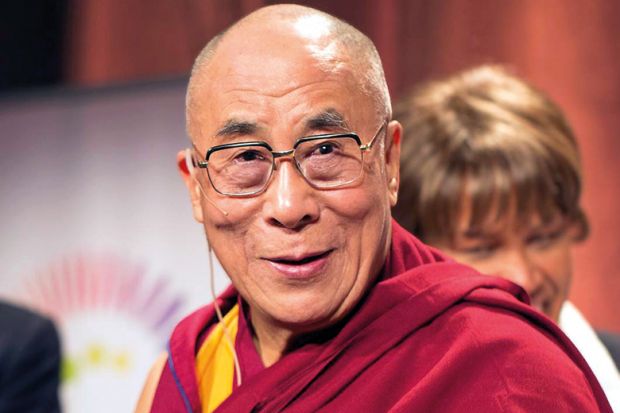

In one sense, the controversy over the University of California, San Diego’s decision to invite the Dalai Lama to give its commencement address in June is just another incident in the ongoing tug of war between intellectual diversity and “safe spaces”. But it highlights particularly neatly the absurdity of demanding a campus free of ideological challenge.

While some Chinese students have welcomed the Dalai Lama’s invitation, it has triggered condemnation from the university’s branch of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), which reportedly plans to “resist the university’s unreasonable behaviour”. In response, the university has promised an “apolitical” speech.

Generally, the disagreement over safe space hinges on two factors. The first is whether exposure to particular ideas (rather than threats of violence or actual violent conduct) can be sufficiently assaultive or alienating to necessitate protection. Some, reasonably, fail to see the threat in such exposure.

Even so, there is nothing controversial about seeking a safe space by joining a private club or declining to attend a talk. What makes the demand especially vexing in the university context is a second factor: the implication that the entire campus must function as a kind of symbolic safe space. Those who object to an official speaker invitation in these terms are not simply asking to be spared the compulsion to actually listen to something they find abhorrent. Rather, they are in essence contending that the mere association between their campus and the reviled speaker is an affront – even if they are free to boycott or protest against the speech. An opinion piece in the local student newspaper, for instance, lamented that the Dalai Lama’s mere “presence” will “ruin [Chinese students'] joy”.

A further refrain has been that the Dalai Lama is “oppressive” and “divisive”, with some likening him to Osama bin Laden. Elsewhere, the CSSA cites violations of the university’s own commitment to principles such as “respect and accommodation”.

These terms shrewdly invoke fear and victimhood rather than political disagreement. As Judith Shulevitz noted in a 2015 New York Times article, this “quasi-medicalised” language undoubtedly makes protection seem more urgent for university administrators. Yet there are clear objections to this framing. Most fundamentally, one does not require deep expertise in the politics of the region (and I have none) to be sceptical of such an asymmetrical presentation of the power dynamic. Political disagreements are, by nature, divisive. Moreover, unlike a vitriolic provocateur such as Milo Yiannopoulos, the Dalai Lama has the support of respected human rights groups such as Amnesty International, as well as the Nobel Committee, who awarded him the 1989 peace prize.

Ultimately, the problem here is with the particular conception of what it means to be accommodated and respected in a university. This cannot depend on the university’s showing deference to one’s pre-existing understanding of the world. In fact, if UCSD’s attitude towards the Dalai Lama really represented a test of its inclusion of Chinese students, why stop with commencement? Why not publicly disavow the Dalai Lama and portray him in its courses as he is portrayed in Chinese state media? At a certain point, such requirements for ideological accommodation become impossible to fulfil.

Whether or not the Dalai Lama discusses a topic such as Tibetan independence, Chinese students have rightly pointed out that his very presence is symbolic of a political position. The university understandably does not want to alienate this key constituency further, and that is nominally a positive impulse. At the same time, the concession of a putatively “apolitical” speech dodges the political dissonance that clearly exists. The Dalai Lama is already revered by many in the US, and, to some degree, his invitation by UCSD reinforces that reverence. There must be a way to reassure students from China that they are welcome without pretending that the university is ideologically neutral.

Those who object to the Dalai Lama should try to persuade the public that their assessment of his actions is the correct one. If they protest against the speech, they at least have an opportunity to remind commencement onlookers and media audiences that he is, in fact, a political figure rather than an anodyne spiritual mascot. Any resolution that relies on shirking confrontation of the ideological dissonance is, however, an unsustainable foundation on which to build a cosmopolitan university community.

Ben Medeiros is a lecturer in the department of communication at the University of California, San Diego.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Contesting views

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login