Academics should resist signing over the copyright of their research to a “profit-oriented” academic publisher if they can secure a licence to publish themselves, a report recommends, while university leaders must simultaneously seek ways to ensure that copyright remains with the author.

According to the report, Untangling Academic Publishing: A History of the Relationship between Commercial Interests, Academic Prestige and the Circulation of Knowledge, reforms of scholarly publishing have given “undue weight to commercial concerns” in recent years. Additionally, the “prestige economy”, in which academics compete for the kudos of having their work published by journals with high impact factors or by high-status presses, has stymied the move towards open access and “free sharing of knowledge”, it argues.

“Academics should not sign copyright transfer forms that would give ownership to a profit-oriented publisher if a licence to publish can be granted instead,” the report states. “University leaders should introduce measures (such as the UK Scholarly Communications Licence) to ensure that the copyright in academic work is retained by its creator, rather than being transferred in toto to third-party organisations.”

This, it adds, will be an “appropriate rebalancing” that allows researchers to assume “greater responsibility in the dissemination of the fruits of their work”.

The report – authored by Aileen Fyfe, Noah Moxham and Camilla Mørk Røstvik of the University of St Andrews; Kelly Coate, senior lecturer in higher education at King's College London; Stephen Curry, professor of structural biology at Imperial College London; and Stuart Lawson, doctoral researcher at Birkbeck, University of London – notes that the growth of academic publishing has put strain on the academy, with scholars having to undertake more work as peer reviewers and editors, and university library budgets struggling to keep up with rising prices.

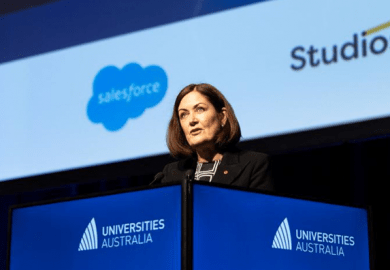

Dr Fyfe, project lead and reader in St Andrews’ School of History, told Times Higher Education that the attitudes towards academic publishing need to shift at all levels.

“At a big scale, government research agencies are going to have to rethink the incentives that they’re offering at the moment, how they’re thinking about academic publishing,” she said. “I would like to think that vice-chancellors are going to read [the report] and think: ‘Oh, we need to change our promotions processes.’ But until the government does something on how to support open access and how it measures research excellence, then the universities won’t change.”

As for scholars and researchers, they should agree that what matters most is “what you publish” and that you “get lots of people to read it”, and focus less on where work is published, Dr Fyfe argued.

Among its other recommendations, the report calls for academic disciplines and learned societies to “embrace” preprint servers as providing opportunities for “more rapid and widespread circulation of research”.

“[They] allow us to communicate with academics around the world faster, more efficiently and indeed more collaboratively than we’ve been able to do in the past,” Dr Fyfe said. “Why wouldn’t we want to use these things? Because our CV wants that thing saying ‘I’m [published] in that particular journal’.”

She added that the emergence of preprint servers such as arXiv and bioRxiv has been reshaping the journals landscape but that monograph publishing was lagging behind.

“[With monographs] there is far less experimentation than is going on in the journal world; we don’t really have any sensible solutions for how we’re going to deal with open access,” Dr Fyfe added.

“All the mission-driven publishers, learned societies and university presses out there are expected to be commercially successful. How do you balance that against the desire to do more good, [to] circulate more knowledge?”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login