Are Americans nice?

If so, what can this tell us about Americans, and about niceness? And if the premise itself is dubious, why have Americans nevertheless embraced it so fervently?

It may seem reductionist to make such characterisations in broad strokes – nice Americans, shifty Italians or greedy Chinese – although assessments like these have been commonplace ever since national identities arose. (Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism offers these appraisals of Chinese and Italians.) A fascination with classification resonates in the 18th century, precisely when “Americans” came on the scene; Diderot’s Encyclopédie describes serious Spaniards, deceitful Greeks, proud Scots, drunk Germans and wicked English.

“National clichés are repetitive, predictable, and unoriginal,” writes Carrie Tirado Bramen, associate professor of English at the University of Buffalo, in American Niceness, “but they are also ideologically powerful and historically rich.” National types are “narratives in concentrated form”, she explains, and even if they are not strictly accurate at first, they may become true – or what the American talk show host Stephen Colbert calls “truthy” – as they persist.

The haughty English were especially salient points of definition; early Americans conceived niceness, in large part, as not-English. The Declaration of Independence paints King George III as “the embodiment of evil”, Bramen writes. The word “nice” itself even changed as it crossed the pond: it had meant “precise”, but we Americans recast it as “pleasing”, valuing pleasantry over exactitude; such slang was quintessentially American, rejecting precise (but outdated) English compulsions and manners.

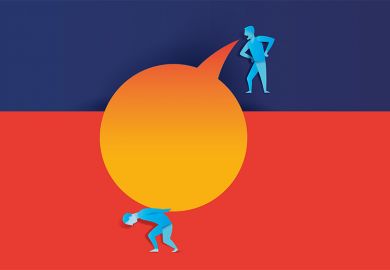

But Americans have not actually been that nice, especially the closer one looks, and such scrutiny is precisely Bramen’s mission: problematising and deconstructing the facade. Cordiality is not equally pleasant for everyone: inequity, suppression and covert power dynamics simmer beneath a nice veneer as some may be smiling through gritted teeth, under duress, while others grin with the smugness of success and triumph. Amiability masks discord.

Bramen’s field of expertise is 19th-century America, but obviously this book must begin in the immediate moment, invoking the bombastic American demagogue who bullies and harangues, offends and insults, with unprecedented vitriol. She quickly confronts and dispatches President Trump as the logical culmination of a tradition in which Americans pretend to embrace comity and harmony while actually sowing prejudice, venality, deceit.

Under the cover of niceness, Americans have done many things that are not at all nice: Native American genocide and slavery at the start, setting the stage for more free-ranging racism, sexism and imperialism. Bramen teases out the constructions (and underlying contradictions) of how we imagine ourselves, and who we really are. She discusses how niceness, and, of course, the manipulation of this idea, was invoked to sustain American exceptionalism. We are the best because we are nice, and we can do anything we want because, again, we are very nice. If this sounds facile, then an entire geopolitical behemoth, the American empire, has been built on the foundation of such prattle.

Catharine Maria Sedgwick, the patrician New England author of The Poor Rich Man, and the Rich Poor Man, meant for her 1836 novel to be “simultaneously a response to the growing disparities between rich and poor in the early republic and a way of reassuring the reader that the American poor are really not that poor when compared to other parts of the world”, Bramen writes. Sedgwick’s niceness is “assimilative” – characters have to be nice if they have any hope of getting ahead – and such an atmosphere serves “to mitigate the threat of working-class animosity”. Bramen describes the strategy of “affective conversion” – how people’s feelings and emotions are refashioned to something more pleasant, less threatening. Thus “the poor behave less bitterly and the wealthy feel less guilty by giving niceness the power to convert sour faces into a ‘harvest of smiles.’ A democratic nation is one whose citizens smile together.”

“Welcome, Englishman,” said Samoset, an Abenaki native, to the Pilgrims at Plymouth, in what Bramen calls “the primal scene of American niceness”. These native societies were indeed nice: Karl Marx, studying Iroquois ethnography, was impressed by how Native Americans lived simply, harmoniously, communally. But the settlement story unfolds as a catastrophic betrayal. “Indians helped the first settlers to survive,” as Bramen puts it, “and as soon as they acquired the necessary tools, they killed their indigenous hosts.” Although she doesn’t quote Leo Durocher, the legendary manager of the LA Dodgers – “Nice guys finish last” – I heard that maxim resonating throughout this book. (Durocher was not a nice guy; rather, his teams won ballgames.)

“The theme of hospitality betrayed is an important refrain in Native American writing of the nineteenth century,” Bramen writes. Jacques Derrida observes that hospitality and hostility share the same Latin root. Hospitality, although nice, is “an ambiguous relation that is fundamentally risky”, Bramen warns. In the event, “By inviting the hungry guests inside their homes, literally and figuratively, Native Americans sowed the seeds of their own demise.” A Lenape narrative offers a retrospective awareness of how Native Americans saw their tragedy: “We received them as friends...We thought they must be a good people. We were mistaken.”

White Americans wondered about African Americans, too: are they hospitable and kind, or dangerous and savage? Whites tried to decode the semiotics of the Black smile: “is it a sign of genuine contentment or a veil of concealed rage?” For the pro-slavery camp, smiling slaves demonstrated that the system was not so bad after all; slaves seemed relatively content. Many Americans embraced a fantasy of consensual slavery: Oliver Wendell Holmes felt that the affection between those who were owned and those who owned them implied that America had established “slavery in its best and mildest form”. Southern hospitality, America’s most exaggerated trope of niceness (set in its most violent region), was “a mask that conceals the necessary cruelty of the system”, Bramen writes, “a cultural charade”.

Today, Americans travelling abroad sometimes disguise ourselves with Canadian T-shirts so we won’t have to explain or defend rampant gun violence, Islamophobia, geopolitical isolationism, drinking water that poisons poor people, hair-trigger shootings that kill Black people, unsustainably incontinent carbon footprints.

Certainly there are nice Americans as well – my wife is lovely, our sons are mensches (as are their friends), my students and colleagues are swell, people I meet in the park are pleasant, and not just politely but, I think, fundamentally nice: eager to help those in need, trying to make the world better. I appreciate these people I find all around me, grateful to be part of a community embodying so much niceness.

But this is not to challenge Bramen’s thesis: she is right that American niceness, a coercive strategy, is often not genuine. Long-standing myths created to hide exploitation endure in the present, supplanting a frank reckoning of our national character. After reading American Niceness, I feel that we have some pretty glaring blind spots that it would behove us to address. (The rest of the world, I think, knows this already.) Consider, by contrast, Germany and the character of fascism. It is probably more intellectually honest, more ethically straightforward, for Germans to grapple with this legacy as they confront themselves in the present than it is for Americans to try to understand our place in the world while fetishising our infinite niceness.

Randy Malamud is Regents’ professor of English at Georgia State University and the author of The Importance of Elsewhere: The Globalist Humanist Tourist, forthcoming from Intellect.

American Niceness: A Cultural History

By Carrie Tirado Bramen

Harvard University Press, 384pp, £35.95

ISBN 9780674976498

Published 25 August 2017

The author

Where were you born and where did you spend your early years?

I was born in Los Angeles, California and spent my early years there before ending up in Danbury, Connecticut (about an hour outside of New York City).

Where did you go to university and how has that shaped your subsequent intellectual development?

I attended the University of Connecticut during the height of Reaganism and, although I had a fantastic academic experience there, the campus scene was stifling and characterised by an oppressive sense of social conformity. Rather than transfer universities within the US, I decided to apply to a new “Junior Year Abroad” programme at Somerville College in Oxford.

The contrast between the university scene in Britain and the US in the early 1980s was striking: I arrived at Oxford at a time of tremendous student activism and political consciousness around the miners’ strike, Thatcherism and its impact on student grants, and US foreign policy in Central America.

Somerville, which was still a women’s college in 1984, was a transformative place personally, because it embraced and validated eccentric intellectual young women such as myself. Somerville taught me how to take myself seriously, largely by observing my peers and noticing how many of them approached their studies with admirable discipline and focus.

How has an education in both the UK and US helped you to see aspects of trans-Atlantic relations others might miss?

When I arrived at Somerville, I was as green as they come. I remember pulling my suitcase across the quad and cheerfully saying “Good morning” to a don as we passed each other, and she stopped and stared at me with a look of surprise and contempt and said nothing…So that was my first encounter with a different mode of sociality that was perhaps more pronounced in the 1980s (especially at a place like Oxford) than it is today.

My year at Sussex in the late 1980s was significantly different, as I was studying in the MA programme in critical theory with an extraordinary faculty consisting of Jacqueline Rose, Rachel Bowlby, Alan Sinfield, Jonathan Dollimore and Homi Bhabha among many others. Our student cohort consisted of amazing thinkers with brilliant senses of humour and it was characterised by a rare synergy between intellectual rigour and pleasure.

[But there is also] a latent genre of American confessionals of failed trans-Atlantic bonding, especially among Americans who expected intellectual kinship and instead felt rebuffed. I think this trans-Atlantic disconnect comes partly from the fact that the British do not have the disease to please, which must be very liberating. I am both envious of this quality and a bit bemused by it. At the same time, I don’t want to be a champion of American niceness as this facile and unproblematic national affect. American niceness can be charming, but it is important to see its multifaceted aspects, including its shadow side.

What led you to the unexpected theme of “niceness”?

Jay Fliegelman, one of my professors at Stanford, used to say that every book is an autobiography. I do think that is true. As someone who has been married to a Brit for 25 years (we met at Sussex), I joke that this book is a displaced way of making sense of our trans-Atlantic marriage.

With that confession aside, there is also a deeply political line of inquiry. It came out of the aftermath of 9/11 as a way to make sense of the ubiquitous question one heard at the time: “Why do they hate us?” I was struck by that question, which reduces a complex political event to an interpersonal matter of liking or hating.

I decided to explore databases for articles written in the UK during the IRA bombings in the 1970s and 1980s to see if any UK newspapers asked the question “Why do the Irish hate us?” Not one article appeared in the British press asking that question. Why? I asked English friends and they all uniformly responded with a version of the following sentiment: “We bloody well know why the Irish hate us.” Where the English acknowledge Irish hatred (regardless of their feelings about the Troubles), Americans have to disavow reasons for Middle Eastern hatred because we have to maintain the myth of being a fundamentally decent people, more sinned against than sinning.

Have you personally witnessed encounters between Americans and Europeans where the issue of “niceness” was at stake?

I have had a few conversations with Europeans (British and Germans, to be precise) who were utterly confused by how to interpret American niceness. One German colleague told me that her sister had warned her not to confuse American friendliness with an invitation for friendship. This seems to be the biggest European mistake that leads to much frustration.

Has the advent of Donald Trump exploded the idea of American niceness – and can you see it making a comeback?

Despite the poisonous tone of much political discourse in the US today, the idea of niceness persists. At mass protests such as the Women’s March, signs read: “Empathy”, “Be Nice”, “Make America Kind Again” and "This is not an anti-Trump rally – this is about caring". I am struck by how resistance against Trump has taken such a strong affective form.

There is an earnestness to the public rhetoric that I think is an important counter to the “hermeneutics of suspicion” that characterised much academic thinking a generation ago. Academics need to take this earnestness seriously. I began this project sceptical about the interpersonal turn in post-9/11 America epitomised by the question “Why do they hate us?” Writing about niceness – both its strengths and shortcomings – has taught me that the interpersonal can play a vital role in establishing social bonds that can re-humanise us in these deeply dehumanising times by forging networks of solidarity to counter militarism and neoliberal policies.

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Toothy grins mask many sins

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login