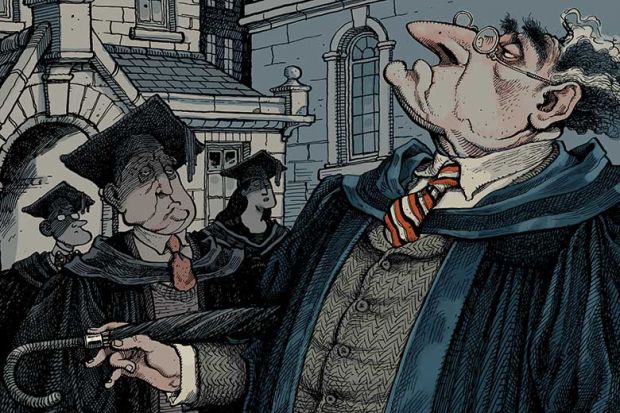

Why do academics, in their professional writings, refer to one another by their surnames only? It may be tempting to answer that this is the convention: “everybody does it”. While that is a compelling explanation, however, it is not a good justification.

The practice does require a justification because in virtually all other contexts it is impolite to refer to people without using either first names, which are personalising and friendly, or titles, which convey respect. Most of us do not call our friends, colleagues or others by their surnames only.

There are exceptions, such as the military and British public schools. However, while these are formal environments (which explains the more respectful ways in which “superiors” are addressed in those contexts), they are also deindividualising and harsh cultures. They are, thus, not the touchstone of politeness.

To be fair, there are occasions when even academics regard the surname-only conventions as uncouth, and depart from it. When, for example, the scholar spoken about at a symposium is present, they are often referred to either by first name or by title and surname.

Occasionally, such collegiality even carries over into academic writing. For example, while paying tribute to his mentor, Derek Parfit, in the acknowledgements of his 2015 book Rethinking the Good, Rutgers University philosopher Larry Temkin refers to him repeatedly as “Derek”. However, the celebrated Oxford thinker remains “Parfit” elsewhere in the book. The psychologist Daniel Kahneman refers endearingly, throughout his 2012 book Thinking, Fast and Slow, to his late collaborator, Amos Tversky, as “Amos”.

Responding to colleagues writing in a 2010 Festschrift for him, Ethics and Humanity, the King’s College London philosopher Jonathan Glover notes that in “real life, I do not talk about Davis, Keshen, and McMahan, but about Ann, Richard and Jeff…who are colleagues and friends”. He says that the “formality is a bit uncomfortable”, but explains that he nonetheless refers to them by their surnames “so that others do not think the book is a private conversation from which they are excluded”. The concern to avoid exclusion is admirable, but I am not convinced that using first names would indeed have been exclusionary.

Admittedly, however, using first names would usually be too familiar. It would hardly be appropriate to refer to Immanuel Kant as “Immanuel” – never mind “Manny”! First names are also insufficiently individuating in many instances. Davids are ubiquitous, so “Hume” is a more successful reference. However, a reference to “Smith” is unlikely to be clearer than one to “Adam”. Politeness and clarity would be better served by using either both first and last names, or title and surname.

Some will take the former option to be too cumbersome and the latter too formal. I am not convinced that these objections outweigh the benefits. Nor am I convinced by the objections on their own terms. After all, The New York Times successfully uses title and surname while preserving a readable style and avoiding excessive formality.

Those who think that a similar approach would not work in academic journals should be reminded that there was a more respectful time when scholarly journals contained articles with titles such as “Professor Sidgwick’s Utilitarianism” (Mind, 1885), in which Hastings Rashdall unswervingly refers to “Prof. Sidgwick” throughout. I don’t find this distracting, but readers are at liberty to gloss over “Prof.”, or to read the title and name as they would a double-barrelled surname.

Some will think that this is prissy. That view, however, cannot be used to defend the status quo, because it is standard practice in some domains to use more respectful forms of reference. Judges are routinely referred to with their titles, and even law journals commonly refer to “Judge (or Justice) Bloggs”, or by abbreviation to “Bloggs J”.

This gives rise to curious inconsistencies. In a 2012 review of New York University legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron’s book The Harm in Hate Speech, the former Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens repeatedly refers to “Waldron”, while referring to judges by their titles. Sometimes the jarring differential is in the same sentence: “Waldron also contends that Justice Black’s position is unwise.”

Such inconsistencies also undermine the suggestion that “Jeremy Waldron” and “Waldron” refer to different things – the former to the human being and the latter to the collection of views expressed by that human. If that distinction were anything other than a rationalisation we would expect it to apply to judges too.

That said, even The New York Times refers to “Shakespeare”. Its practice is to drop titles for “historic or pre-eminent figures no longer living” – unless they are “being discussed in the context of current news events”. The stated justification is to “avoid sounding odd or tone-deaf”. But it certainly does not follow that we should drop everybody’s title.

The coarseness of referring to people by their surnames only is obscured by its pervasiveness. We can do better. A less aggressive and more respectful tone would be far more appropriate, especially when criticising the views of others, and I encourage others to join me in adopting one. As popular debate in the social media age becomes ever more uncivil and intemperate, academics would do well to set a better example.

David Benatar is a professor in the department of philosophy at the University of Cape Town.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Where are our manners?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login