It is a truism that the road to success is paved with failure. Yet in a hyper-competitive era of academic competition, in which everyone strives to present a fundable and promotable veneer of global excellence, admitting to any such missteps can be perilous. Recognition of that fact was the motivation for Johannes Haushofer, assistant professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University, when he published his “CV of failure” in 2016. The CV listed all the rejection he had faced in his academic career, such as jobs and grants.

“Most of what I try fails, but these failures are often invisible, while the successes are visible,” he explained. “I have noticed that this sometimes gives others the impression that most things work out for me. As a result, they are more likely to attribute their own failures to themselves, rather than the fact that the world is stochastic, applications are crapshoots and selection committees and referees have bad days.”

Haushofer subsequently faced criticism that his endeavour risked giving the false impression that persistence will always lead to success, neglecting the influence of good fortune. However, if it is another truism that failure is the best teacher, Haushofer seems right to point out that its instruction casts light not only on the aptitudes of the individual concerned but also on the strengths and weaknesses of the system of which they are a part.

In that spirit, we asked six scholars to tell us about the greatest mistake they have made in their careers – and what it told them about modern universities, students and the societies they inhabit.

Notes and queries

I know that I have made many mistakes over my 30 years as a professor of history. One of the most disturbing is to have always dismissed the truth of George Santayana’s old chestnut – that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

Actually, it turns out, Santayana was on to an important truth – but it isn’t the whole story. After so many years of fitful reflection on teaching, I have learned that even when I do remember the past, I am condemned to make different kinds of mistakes.

Here’s one instance: my lecture style. When I first began to teach, I wrote out my lectures. Word. For. Word. This included my killer jokes, casual asides and, yes, stage directions. (Pause.) Invariably, the jokes fell flatter than the Texas Panhandle, while the asides were as enthralling as endnotes – which, by the way, were also in my lectures. I had wits enough, at least, not to read them aloud – which is more than can be said for some of the professors I encountered during my graduate studies. But their dry-as-dust spirit already infused my lectures.

At the time, I told myself that I was doing the right thing, enacting the model of a proper historian. But I knew deep down that I was doing the wrong thing because I was afraid to enact what I always told my students: that historians are first and foremost storytellers. If a historian fails to capture your imagination, all the while cleaving to the documented record, then she has failed in her job.

We need to supplement Santayana’s wisdom with that of Woody Allen: those who cannot retell the past should be condemned to teach gym.

As a member of a team-taught course, I had the good fortune to watch colleagues for whom teaching and reciting were not one and the same. (And I had the equally good fortune to watch those for whom it was.) As a result, I eventually mustered the courage to end my dependency on written lectures. It was a gradual process, but a liberating one. When I finally tossed aside these pedagogical crutches, I felt as if I could run.

And run I did. But here’s the rub: I often ran smack into walls of my own making. Where I had once been afraid to take my eyes off my lecture texts, I was now afraid to turn my eyes to them. Even a glance, I worried, would disturb the narrative flow and dent my credibility as a storyteller. Indeed, I was all the more anxious given the ubiquity of YouTube, Instagram and the like – realms where spontaneity is prized and scripts are prehistoric.

The consequence was that, at times, I forgot what I should have remembered, and said what I should have refrained from saying. In other words, I would fill the blank with blather. Slowly sliding down this slippery slope, I would fudge the explanation, telling myself that while I might be getting the details wrong, I was getting the deeper truths right. I prided myself that I was emulating the acclaimed pianist Arthur Rubinstein, who, I once read, proudly owned that he made mistakes while playing, but that no one made them better than he did. (Though perhaps I am also fudging that story.)

Over recent years, I have tried to clamber back up this particular slope by again using lecture notes. Not the texts of entire lectures, mind you, but points too important to forget or fudge. Yet, with my hair grey and gait slower, my new fear is that my students will think my memory is faltering. And so, I scribble these reminders on to multi-coloured sticky notes, which I conceal in the books we are discussing in class. Of course, I now sometimes find that I cannot decipher what I wrote, or determine why I wrote what I did.

But did you know that the great Rubinstein also plastered sticky notes, covered with the notes for his credenzas, under the hood of his Steinway? No? Ah, have I got a lecture for you!

Robert Zaretsky is a professor in the Honors College, University of Houston.

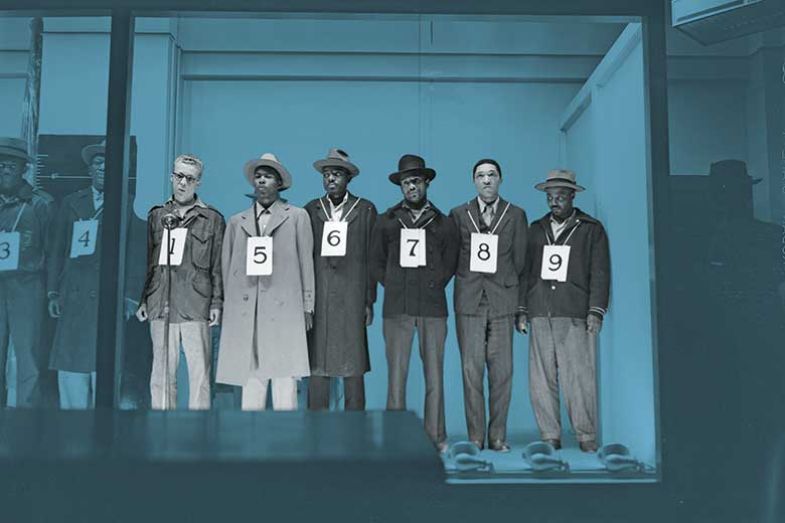

Mistaken identity

In January 2002, I was a mathematics graduate student, assigned to teach my first-ever class: calculus for non-mathematics majors. Armed with interesting calculus applications concerning computer graphics, weather patterns, firefly synchronisations, population growth and disease spread, I assumed that all those aspiring poets, musicians, painters, historians, political scientists and philosophers would get a lot out of my first set of appearances working through problems at the blackboard.

Then I met Jamal (not his real name), an enrolled student with no intention of working. How did I know? He raised his hand in the third class and said something like: “I don’t wanna work this hard! This was supposed to be an easy class for non-math students!”

I responded with a not-so-short soliloquy about the joy in distinguishing between a derivative and a differential in calculus. He rolled his eyes. I returned to my prepared lecture.

As the weeks passed, Jamal continued to voice loud, confrontational complaints. Lacking training and experience in classroom management, I assumed he simply needed extra maths help, so I extended invitations for him to visit my office hours. Once, he responded by saying something like: “I don’t have time for office hours! Your expectations are way too high!”

My patience was running thin. But Jamal was not the only reason. I was pregnant. It was news I welcomed. However, when an influential graduate professor in my department learned of my pregnancy, he told me point blank that “motherhood is incompatible with mathematics”. He also clarified that graduate students were ineligible for maternity leave and that I would be asked to leave the programme if I needed time off after giving birth. Two other graduate women in my department had tried to combine pregnancy with graduate school but left before earning the degree for reasons I was only then beginning to understand. As it stood, I was the only woman remaining in my graduate cohort. Nationwide at the time, less than one-third of new mathematics doctoral recipients were women. Among senior faculty, female representation was far worse.

Not long after, Jamal showed up in my office. Feeling sorry for myself, I made the mistake of speaking first and without thought. In my memory, I said something like: “Jamal, is the worst that you can say about me that my expectations are too high?! You might’ve said I need to be less nervous when teaching! Or that I don’t relate to undergrads! Or that I selected a terrible textbook – because I did! Or that I need to turn around from the blackboard more to notice raised hands! But you’re concerned that my expectations are too high?! You’re an African American man! Get mad at anyone who doesn’t expect much from you! Especially in a challenging subject like calculus! You don’t think I know what it is to be underrepresented?! Try, for a day, being the only woman left in your graduate cohort! And then try being that woman while pregnant!”

Upon realising that I had revealed my pregnancy, which had not previously been evident, I stopped. In the silence, I realised that I had crossed a professional line. Still, it hardly seemed to matter; my dissertation research was going well and my graduate teaching evaluations were above average but, apparently, I would be kicked out of graduate school anyway owing to my pregnancy.

Jamal left without comment.

That night, I wrote my next lecture with a heavy heart. The fire at Ground Zero following the World Trade Center terrorist attacks had only stopped burning one month earlier and the devastation of 9/11 remained palpable. My first-generation American parents were Bronx and Brooklyn natives. I had grown up in metro New York. My favourite pastime, reading The New York Times, only offered reminders of evil. Funny movies felt unrelatable. But at least mathematics provided solace. I could see that, even if my students could not. Still, I needed – and wanted – to apologise to Jamal.

When he stopped by my office the next day, I made sure to let him speak first. He said something like: “There’s something I want to tell you. I’m not African American. I’m from [an island in the Caribbean]. I’m Muslim.”

I told him that I was sorry: that I never should have referred to his identity, much less gotten it so wrong. He forgave me, noting that he only told me because he believed I would want to know. He was right.

Then he added something like: You know, Islam is the crux of my identity. I’ve been having a hard time since 9/11. Some students in my dorm made harsh comments and others I thought were friends now stay away. I’ve been angry and feeling sorry for myself. But you, my calculus teacher, have reminded me of my Islamic values. I grew up on a farm where my father tried to impart that righteousness comes through hard work. You’ve reminded me of that. I was wondering if maybe you had time to talk about the difference between a derivative and a differential? I know you said it was interesting.

I took out my pencil and invited him to sit down.

Susan D’Agostino began and completed her PhD in mathematics at Dartmouth College without the benefit of maternity leave. (The college began offering maternity leave to graduate students in 2006.) She is currently a Taylor Blakeslee Fellow of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing at Johns Hopkins University.

Anger management

This year marks the tenth anniversary of my biggest career mistake. This mistake was not itself a particular event, but rather a prolonged unproductive response to events.

In 2009, I was denied tenure at the university where I worked. The decision shocked the community and colleagues in my research field. It was inconsistent with previous and subsequent decisions of the faculty committee, and with feedback that I received. I never got a satisfactory explanation.

In the lead-up to the decision, I had worked hard, at the expense of sleep, health and time with my family. I told myself that this was necessary for the outcome I desired, and would all be worth it. But this was not my biggest mistake. I did what I felt needed to be done. I made mistakes along the way, but I took my career seriously and gave it my all. If I hadn’t, given the outcome, I’m sure that would be my biggest regret.

Honestly, nothing I did before the decision was a big mistake. I am proud of my research, teaching and service, and of the accomplishments of my doctoral students, during and after their time under my mentorship. I showed up as my authentic self, and lived my values. I earned respect and affection from colleagues. I felt a sense of belonging to the place where I made my early career.

The mistake came in the aftermath, in how I managed – or mismanaged – disappointment and grief. I internalised failure. I told myself that I was joking and disarming detractors when I referred to myself – as I frequently did – as a “failed scientist”, but, in reality, I let anger and despair consume me. I speculated endlessly about what had happened and why. My response delayed the process of facing my loss and allowing myself to grieve productively. Delayed grief meant delayed healing.

Although I made a quick, decisive and positive career pivot, and kept my marriage and family life intact, my victim’s mindset took a toll on personal happiness and professional development. I still don’t know exactly what happened, and this isn’t uncommon. But my life, health, happiness and career advancement improved immeasurably when I made the decision to stop wondering and let go of anger, bitterness and hopelessness. That’s a longer story – and an upbeat, positive one – that I’d like to tell some other time.

Someone I follow on Twitter recently asked: “Why does academia make people feel shame, failure and doubt?” Leaving aside that each of us is solely responsible for our feelings, I do think that a caustic, outsized fear of failure runs though academic life. The scarcity of tenure-track jobs and the up-or-out nature of tenure decisions creates a culture of winners and losers, victors and victims. Minor distinctions are amplified by careless procedural sloppiness, resulting in such all-or-nothing binaries: bliss or the abyss. The successful academic career that I built for myself post-tenure denial required a conscious choice to undo years of damage that I had allowed that mindset to create.

Mary Ellen Lane is dean of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and professor of neurobiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Critical mass

During a recent seminar for PhD students, I reflected on what, really, doing my PhD taught me.

While I learned a great deal about gender and social theory, more than anything else it taught me how to approach the world critically. Being critical is an essential skill for academics – particularly for social scientists. This stance manifests itself in many ways: I am no longer capable, for example, of reading a newspaper front page without thinking about the discourse shaping the media message. Listening to politicians discuss their approach to tackling “gangs” in London, meanwhile, is an exercise in self-restraint as I roll my eyes in exasperation, knowing that they are presenting their views in a way that will win over voters rather than actually address the real problems facing young people.

But I have also learned that the virtue of a critical stance has its limits. Indeed, the biggest mistake I made in the earliest stages of my career was to assume that expressing critical opinions in every situation with total honesty was not only necessary but desirable. It would seem that I am not the only one with this perspective – as can so easily be seen at conferences and symposia, during upgrade panels for PhD students, and perhaps most clearly in the peer review process.

Reading the work of another scholar and providing feedback needs to be done with a critical eye, and all academics rely on good peer review comments to make our work better. In the best moments, the process is like a conversation between colleagues, in which a paper is moved closer and closer to excellence with the help and guidance of others who can see what we sometimes miss. But as we know, that, sadly, is rarely the reality.

I remember working with a wonderful colleague whom I have long considered a mentor, contributing to a special issue she was editing. She asked me to review one of the papers that had been submitted, and I spent two or three hours reading it and providing what I felt were appropriate comments. In my email to her, I said the article was unpublishable and, in total confidence of my view, told the author in no uncertain terms about the gaps and flaws in the argumentation – with evidence provided.

My mentor emailed back shortly thereafter, thanking me for taking the time to read and review the article. In the last few lines of her email she gently suggested that my comments, while helpful in many ways, were far too critical and missed the very point of the peer review process. Surprised that she would think this, I read the comments back and I could almost immediately see that she was right. My words did not invite dialogue, with suggestions about how the article could be improved: they amounted to a one-way, overly critical and callous presentation of my own final verdict (albeit that I still believe the verdict was valid).

The comments from the other peer reviewers were much more constructive, and the final published paper was an excellent contribution to the collection, no thanks to me. I hadn’t tried to see the bigger picture and think about what the article could do. I had only thought about where the failings were, and had taken a certain glee in pointing these out.

Hubris and an element of Schadenfreude seem to go hand in hand in academia, and most readers will recall with alacrity the overly harsh peer reviews they have received over the years; fewer, though, will remember writing similar comments themselves. We are alarmingly myopic when it comes to reflecting on our own shortcomings. And because we must be critical in order to make a meaningful contribution to social science, it is easy to forget that not all situations require the same forceful application.

Not everyone will share this view, but when I take a step back, it seems to me that my primary role as an academic is to try to create a better world. That is why I wish I had been able to be kinder in certain moments, and to genuinely try to help, rather than simply tearing down. Kindness is in short supply in academia – and we would all do well to try to infuse our critical perspectives with more generosity of spirit.

Erin Sanders-McDonagh is senior lecturer in criminology at the University of Kent.

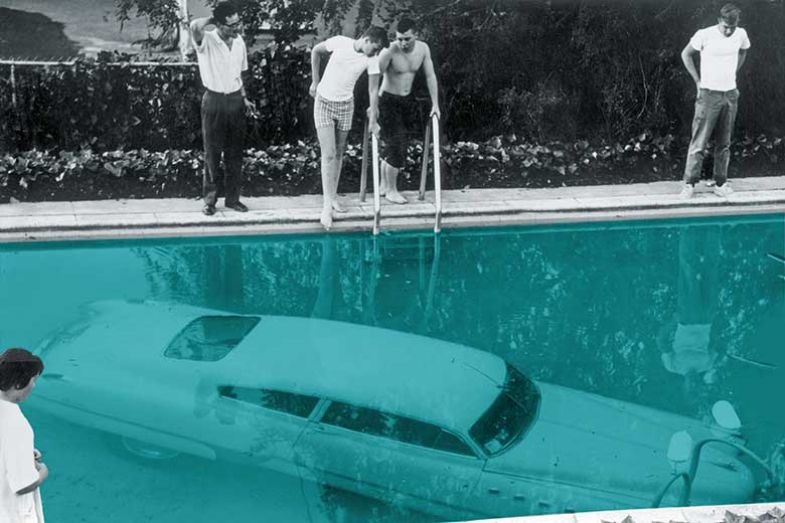

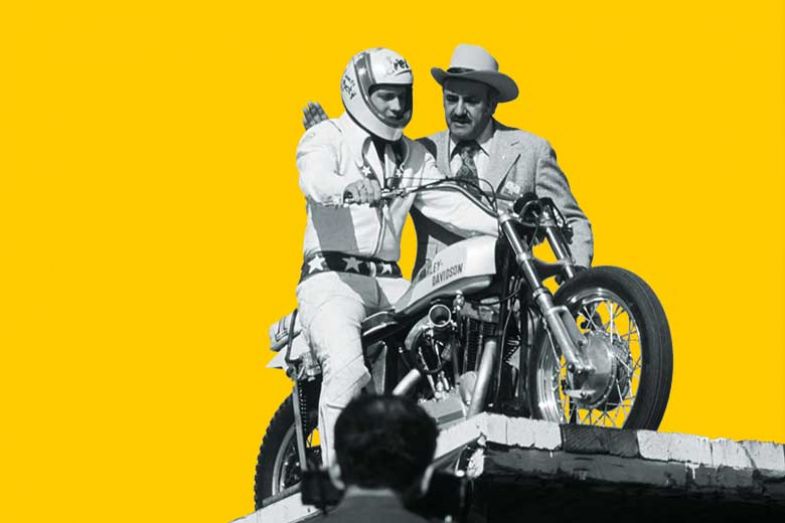

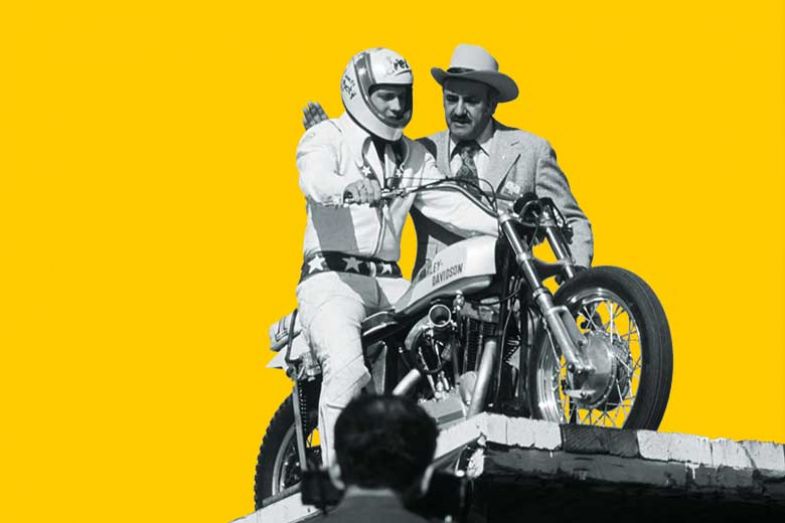

Leaping and looking

According to Albert Einstein, “a person who never made a mistake never tried anything new”. So the question academics should perhaps be asking ourselves is whether we have failed enough.

I can certainly say that, as a young academic, I was never afraid of throwing my hat into the ring. That fearless attitude had served me well previously. I graduated during the 1992 recession and, struggling to find my first job, turned to the market for “fast, accurate typists” with a grasp of various word-processing packages.

At first, I was up front in my cover letters about the packages I knew about, but after I drew another blank my best friend set me straight.

“Honesty is not the best policy,” she declared, urging me to proclaim proficiency in all packages, and use my research skills to get up to speed on the job. After all, how difficult could that be for someone with a first-class economics degree?

Of course, she was right. I got the job – while she went on to write books about employability: clearly, she found her niche early!

But the proof of a good strategy comes in its ability to consistently yield positive results. My bestie’s approach was put to the ultimate test when I was invited, as an academic, to present a paper on commodity forecasting at a capacity-building workshop in Cameroon. At the time, I was forecasting coffee prices for the Association of Coffee Producing Countries, so the request was not outside my comfort zone, apart from one little snag: the speech had to be delivered in French.

My expertise in French was reflected by the N grade (a near fail, awarded when the pass mark is narrowly missed) in the A level that I had taken at evening classes a few years earlier. But I had expert support at hand: a colleague at the association was from the Ivory Coast and agreed to translate my presentation, meaning I would only need to read it at the conference. Voilà!

The first thing that went wrong was my time management. Balancing work commitments and conference preparation proved difficult, so I only managed to get my slides produced and translated before leaving for Cameroon. Like all good goal-setters, I adjusted my plan, confirming with my colleague that I would write the speech on the plane and then email or fax it to him.

Once I arrived in Cameroon, mistake number two hit me hard. This was the assumption that I would be able to contact my colleague easily. In reality, fax machines and internet connections were either not available or not working. I also had to travel miles from the airport to the hotel, leaving little time to find a solution to this problem. Ultimately, there was no time for translation. I was on my own. But what could I do after travelling thousands of miles other than deliver the paper?

I began my speech as I begin most things: confidently, aiming to plough through it as quickly as possible. I had already notified the organisers that I would be answering any questions in English, so I had a translator next to me. Halfway through my speech, he tapped me on the shoulder and asked if I would prefer to speak in English and let him translate.

That must have been the single worst moment in my entire academic career. I was obviously taken aback and highly embarrassed. Nevertheless, wanting the whole experience to end as speedily as possible, I declined the offer and continued to subject my audience to what can only be described as my horrendous French – and I use the word French loosely.

Confidence is a great attribute that will carry you far. No mistake is ever the endgame, but merely an opportunity to learn and grow. I tried something new; I readjusted the plan as it unravelled, and I stepped up to the plate when I had to.

Still, 15 years on from that experience, I am ready to admit that boldness needs to be backed up with content. And I have never revisited Cameroon, or delivered another conference paper in a second language again. Writing this piece in the early new year, however, I have resolved to challenge myself in two ways in 2019. First, I will brush up on my French. Second, I will step out of my comfort zone once again. I will take on something new, and fearlessly face the prospect of making a total mess of it.

Karen Kufuor is principal lecturer in organisations, economy and society at the University of Westminster.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

Guidance systems

I started my PhD because it seemed like a good job. I liked doing research, I knew there was a good atmosphere in the research group that had offered me a position, and, since it was in the Netherlands, there was a pay cheque and benefits. I didn’t really have a career plan beyond a conviction that with a degree in computer science I would always be able to find a job as a consultant, programmer or data analyst.

I was lucky to have some wonderful scientific advisers, so I never considered that it might be worth seeking out mentors at a greater distance from my research, to advise me about my career. I enjoyed doing my PhD and embraced all the opportunities that presented themselves to an eager young researcher. I focused on submitting papers to conferences that were good but not too competitive. I said yes to any opportunity that came along. I worked on various side projects (such as competitions to write algorithms to analyse a particular dataset; I never won and often quit halfway) while also reviewing numerous papers and organising workshops. All this undoubtedly added to my CV, but I can see now that I was doing too many activities without a particular focus.

It was only later on during my doctorate that I began to think seriously about staying in academia, eventually deciding that this is what I wanted to do. However, I didn’t feel confident in my ability to meet all the challenges that such a career path would present. I remember feeling embarrassed even to tell my advisers that I was considering it, much less other academics. It felt to me like they would have laughed because the chances of staying in academia are so low – although, of course, I know they wouldn’t have.

My confidence received a welcome boost when Aasa Feragen, then a postdoc and now associate professor of image analysis, computational modelling and geometry at the University of Copenhagen, invited me for a research visit to the University of Tübingen, where she was working at the time. During that visit I also met Chloé Azencott, then a postdoc and now a tenured researcher at Mines ParisTech, Institut Curie and France’s National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM). Both of these women had been awarded their PhDs just a few years earlier and, thus, were much more similar to me than my male, somewhat older formal advisers. They recognised my insecurities and helped me to gain enough confidence in myself to do a postdoc and to search for a faculty position – as well as giving me some useful advice on how to do so.

There is a hidden curriculum in academia: things you are supposed to know, perhaps obvious to some, that no one tells you about. Take funding and awards. I didn’t feel like I needed or deserved any, so I didn’t apply for any during my PhD. Nor was I nominated by my seniors for any awards, such as best paper or poster at a conference – which reinforced my belief that academia wasn’t for me. In retrospect, it feels like common sense to apply for such accolades, and even ask others to nominate you for them.

I also realised that I should have pursued fewer but more impactful publications during my doctorate. Above all, I hadn’t absorbed that there are a variety of mentors that you can learn from, but that you often need to seek them from unusual places.

Since then, I’ve become better at signing up both official and unofficial mentors and asking their advice about next step. For instance, when starting my tenure track position (and feeling nervous about it), I put out a call on Twitter to others in a similar position. With several people who responded, we formed an “assistant professor support group”, which is still around today, and is one of the first places I ask for advice.

But while not realising the importance of having a mentor was certainly a mistake, it was an instructive one, and I don’t ultimately regret it. There is a value to learning things for yourself, rather than absorbing a set of instructions. Perhaps my PhD students will make some useful mistakes of their own – despite my best efforts to support them!

Veronika Cheplygina is an assistant professor at the Medical Image Analysis group at Eindhoven University of Technology.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: My biggest mistake

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login