Many scholars hope to affect, even change, their fields’ usual assumptions. Few manage to achieve this. Andrew Walder, a Stanford sociologist, has done just that. In his path-breaking book, he contradicts the usual version of a blood-drenched period that started in 1966 and was spread across the whole of China. Instead, he maintains that in hundreds of regions, for almost two years, local populations evaded Mao Zedong’s exhortations to exterminate “class enemies”. His central proposition is that “the factional battles...expressed splits among rebel groups...that relisted military control”. It was only in late 1967 that the massive national killing began.

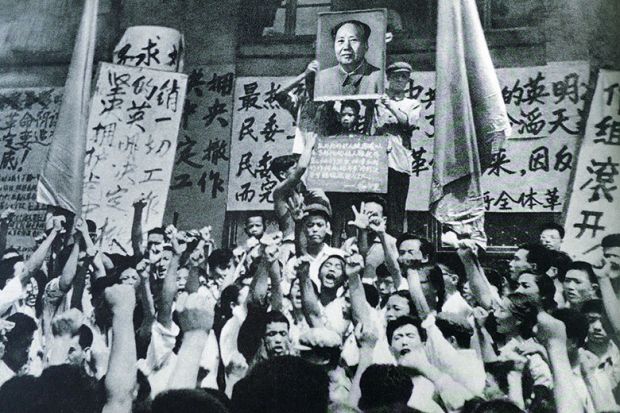

What most of us learned and believed from reading about China or even going there during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was that Mao’s convictions and commands, feared and adored as semi-divine, reached every part of China and almost immediately caused his followers to set upon teachers, landowners, religious leaders and other despised categories to detain, torment and kill them. By the end of a decade, in 1976, millions had been killed.

On the basis of combing through more than 2,000 local documents, however, Walder shows that in many regions humiliations and killings were avoided until late 1967, and that the deaths of well over a million victims were not representative of China as a whole. He emphasises that the horrendous disaster that racked Guangxi province, where huge numbers died, led to the conviction, in China and abroad, that oppression in part of China, in 1966-7, was identical across the whole country.

Here, Walder draws an unexpected but convincing parallel with Charles Tilly’s analysis of the French Revolution: “The rebellion split virtually all social classes and divided Catholic clergy and their congregants against one another. The rebellion did not express class interests in any meaningful sense.”

Drawing on his titanic knowledge, Walder makes a powerful point that echoes, he suggests, the conclusions of historians concentrating on ancient China – that what appear to be all-powerful dynasties were often, after a century or so, riven by local rivalries, which the weakened Han, Tang and Song rulers could not suppress. Unlike them, in late 1967, Mao, who despised and crushed opposition, was able to strike. He decided it was time to resume the long-stalled national campaign, which has given the impression to many observers and researchers that the oppression had begun almost two years earlier.

The local documents, Walder reports, “invariably take a strictly neutral tone: they do not portray one side as more commendable than another”. Instead, then, of a China racked by the national calamity of the Cultural Revolution, in its first two years student and worker rebellions were not especially advanced, and there were thousands of limited events all over China that most of us knew nothing about.

Walder observes that it was usually local groups that had attempted to keep or restore order, such as resisting Red Guards barging into schools. Orthodox Chinese historians have mistakenly attributed this to the central authorities. In fact, we read, “There were 122 reported confrontations with army units initiated by rebel groups during the first four months of 1967.”

Those of us who reflect on Maoist China and today’s president-for-life Xi Jinping, who also crushes any local non-cooperation among Muslims and Buddhists, owe Walder a great debt for our new understanding.

Jonathan Mirsky was formerly associate professor of Chinese history and comparative literature at Dartmouth College in the US.

Agents of Disorder: Inside China’s Cultural Revolution

By Andrew G. Walder

Belknap Press, 240pp, £36.95

ISBN 9780674238329

Published 25 October 2019

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login