A biography is risky business; you hold a life in your hands. Timothy Brennan is perhaps aware of this risk when he emphasises in his title that this book is not the life of the renowned humanist, academic star and activist Edward Said but a life. Indeed, the book is a distinct version of a life – one that places great weight on the intellectual side of things. Brennan has done a herculean job of parsing the monographs, doing interviews and wading through the voluminous archive at Columbia University that includes Said’s drafts, occasional writing, jottings on hotel napkins, even his telephone answering-machine tapes.

As such, the work is much to be commended. Brennan himself has previously written extensively on some of the thinkers and issues that obsessed Said throughout his life and brings his own understanding of Vico, Gramsci, cultural imperialism and empire to elucidate and interrogate various arguments and positions. Thus we get an elegantly written study of Said’s complex relation to the politics of the Middle East, his deep grounding in the philosophers he held close, his overall view of the role of the humanities in society, the place of music in both his analysis and his life, and his position in literary theory and criticism.

But is the life presented the life actually? I ask this question feelingly because I knew Said personally for 35 years. He was my teacher, dissertation adviser, colleague and friend. I lived for many years in the same apartment building as he did, where I could hear him typing late at night directly above my living room. My family shared meals and occasions with Said, his wife Mariam and their children Najla and Wadia.

So the difficulty for me comes from trying to find the man I knew in the biography. Brennan’s book is very much concerned with a philosopher and activist whom readers might feel they are viewing from a lofty and windy distance with an occasional close-up. In that sense, the book is rather more a work of theory and criticism than a pulsing portrait of a person. This isn’t to say that the man is forgotten. There are moments in which we learn how Said made espresso in the mornings for his wife, did laps in the Columbia pool, spent insomniac nights typing on his IBM typewriter and dashed off letters to various friends and mentors. But if readers are looking for deep personal revelations about an academic superstar, they will have to look elsewhere. Said’s own memoir Out of Place will provide more intimate and revelatory moments than Brennan’s book. Likewise, Harold Veeser’s Edward Said: The Charisma of Criticism gives us more of Said’s personality, especially since Veeser played the role of Boswell to Said’s Johnson for several years as he followed him around from one venue to another. And Dominique Eddé’s very personal account, Edward Said: His Thought as a Novel, captures him picture perfect as both man and thinker.

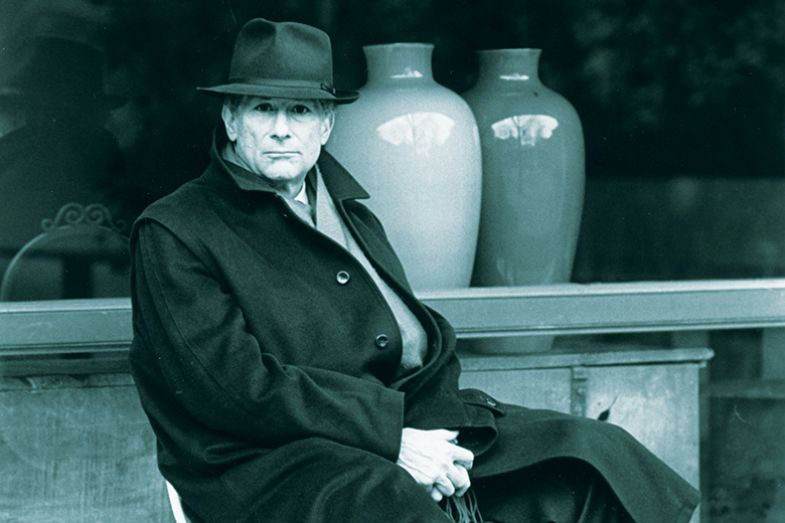

What is missing for me in this book are the contours of the charismatic personality that made Said the figure he was and the academic star he became. His intellect was formidable, but not unique in academia, and while erudite, his knowledge often did not go deeply into any specific field. As Eddé writes: “Said’s work is more than the sum of his books, his writings. It has a great deal to do with eloquence, his charisma, the way that he physically organized the encounter between the written and the spoken.” What was incandescent was his sheer presence. One has only to look at the many videos online to immediately get a sense of this quality. A strong, tall, handsome man dressed in Savile Row bespoke suits with the star quality of a Cary Grant who spoke with a slightly British-accented voice of conviction, passion, authority and humour. You hear the measured cadence of his prose as if writing the words as he speaks them. But the authority of his public presence was easily balanced by the easy-going, self-deprecating, totally funny, irreverent playfulness of his private incarnation. A few times Brennan calls this “childish” or “boyish” behaviour, but that perhaps reflects his preference for the hagiographic rather than the ludic. It is the latter person who would arrive at my door early in the morning with a coffee cup in one hand and a record in the other to share with great joy a particular Handel aria or to come in with a conspiratorial look to gossip about a colleague.

Is such an insight important for an understanding of Said? Perhaps not, but one might ask who, then, is the imagined reader for this work? This is certainly not a book for a general audience who might want insights into the nature of what critic Jeffrey Williams has called the phenomenon of the “academostar”. The true readers of the book would have to be already quite familiar with Said’s writings and activism. For them, a deep dive into Said’s thinking, coursing from one book to another, will be a bracing experience. But will that reader also want to follow the ephemera about the exhausting socialising and travelling he did along with a long litany of friends, former friends, mentors and students?

And then there is the problem of the through line of Said’s thought. Brennan struggles heroically to create a coherent continuity from one book to another, but Said’s own places in the mind won’t really let that happen. He once nervously asked me after a major lecture to a packed audience whether what he had said was coherent or more of a Cook’s Tour. He perhaps understood that he was more an occasional thinker, if not a tour guide, than a system builder. Veeser is more upfront about saying that Said often contradicted himself, and Eddé focuses on what Said called his “contrapuntal” way of thinking. As Said’s much-admired Theodor Adorno said, “The whole is the false.”

Said himself saw his life as “out of place” or, as the original title of his memoir suggests, “not quite right”. Never truly at home anywhere, he lived in the interstices of discourses, locations, social worlds and political affiliations. His genius was to move between them as if there were no barriers. Said decried thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes who created or engaged in totalising systems. To this day, there are no Saidians among his students, though there are Derrideans and Deleuzians. Rather, it is possible to see and appreciate Said as a nomadic thinker who migrated through a variety of topics, often reversing himself. His favourite form, he told me, was the essay not the book. His movement from a supporter of Foucault and other postmodernists to being an anti-theorist; his support for the Palestine Liberation Organization until he rejected it; his various rejections and acceptances of Anglo-American culture; and, as the putative founder of post-colonial studies, his opposition to (or at best tepid tolerance of) that field – all make it hard to create a through line.

The book includes the observations of many of Said’s colleagues, friends and former students, but often these appear as anonymous one-liners that murmur in a whispering gallery rather than engage in a longer conversation about the man. If biography is the art of bringing a life back from the dead, rather than circulating the ideas that remain alive in books, the task of the biographer is very difficult indeed. In his novel Flaubert’s Parrot, which is also a meditation on the art of biography, Julian Barnes’ narrator compares the biographer to a lifeguard desperately trying to resuscitate a dead person on the beach. Brennan’s book is less like CPR on the man and more a eulogy of his mind. For the latter he is to be commended and for the former we can commiserate with his efforts – and that of all biographers.

Lennard Davis is distinguished professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said

By Timothy Brennan

Bloomsbury, 464pp, £25.00

ISBN 9781526612366

Published 18 March 2021

The author

Timothy Brennan, professor of comparative literature and English at the University of Minnesota, was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which he describes as “one of the most segregated cities in the United States”. He studied comparative literature and history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and was particularly influenced by the social historian Harvey Goldberg, “a spectacular orator” who “politicised a generation and certainly moved me and others to form reading groups where we studied the history of trade unionism, revolution, Marxist theory and the anti-colonial movements of Africa, Asia and Latin America”.

Throughout his career, Brennan has been preoccupied with what he calls “the imperial unconscious of the earlier European (and, in my own life, largely American) military and economic terrorism unleashed on poor countries”. This has led to a wide-ranging interest in “peripheral literatures, the role of intellectuals in public life, the history and practice of anti-colonialism, and the role of the university in providing moral and political alternatives. Several of my books [including Salman Rushdie and the Third World: Myths of the Nation] have had a strong biographical strain.”

Asked about the continuing significance of Edward Said and his work, Brennan argues that there could not be “a more symbolically fraught time to revisit the life of the man who single-handedly changed the conversation over Israel and Palestine. People are hungry for victories in a dismal political landscape…Said – in the least likely time imaginable (during the right-wing drift of the Reagan-Thatcher years that led eventually to Donald Trump) – made the humanities dangerous (in a good way) and made the perspectives of the left (on any number of issues, including populism) an institutionally authorised common sense…There has been nothing like his combination of charm, intellectual precision and cultural range before or since.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A portrait short on defining features

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?