Hong Kong universities are in the midst of a cross-border push into neighbouring Guangdong province, where at least four new branch campuses are planned and Hong Kong labs and teaching hospitals are well established.

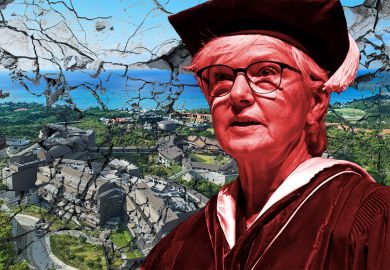

But the opposite has historically not been true. No mainland university had ever proposed venturing into Hong Kong until this month, when the president of Shenzhen University (SZU), Li Qingquan, floated the idea publicly.

“Someone needs to try first,” he told Chinese media. “SZU, as the mainland university closest to Hong Kong, is willing to play this role.”

Such a project from Shenzhen, a Guangdong city known for its technology start-ups, would require unprecedented regulatory approval in Hong Kong, which maintains its own border control and higher education system.

Professor Li admitted to “institutional differences and barriers between the mainland and Hong Kong”, including what would be “undoubtably complicated…legal policy issues”.

But he felt that higher education development in the Greater Bay Area (GBA) – a state project to integrate Hong Kong, Macao and Guangdong – was “only going in one direction”.

“Hong Kong’s young students haven’t profited much from it,” he said of the GBA.

Despite government initiatives – such as well-funded internship programmes – Hong Kong students have proved reluctant to move to an area with fewer political and internet rights.

A 2020 survey by the Hong Kong Guangdong Youth Association showed that only 22 per cent of Hong Kong young adults agreed or strongly agreed with the GBA plans. According to Inkstone News, 60 per cent felt that the GBA would do “more harm than good” to Hong Kong, and about half did not welcome cross-border university interactions.

Gerard Postiglione, emeritus professor of higher education at the University of Hong Kong, told Times Higher Education that “increased interaction between universities in Shenzhen and Hong Kong is inevitable”.

“Solutions to urgent global challenges require nimble knowledge networks. That’s what universities do best. They don’t expand knowledge by closing themselves off from one another,” he said. “The acceleration of technology makes research collaboration both easier and more urgent.”

Michael DeGolyer, a political economist who spent 30 years tracking cross-border relations at Hong Kong Baptist University’s Hong Kong Transition Project, found the Shenzhen idea “encouraging and interesting”.

In his own experiences running cross-border projects, he found that some initiatives “ran afoul of the increased tensions between Hong Kong and mainland students that started boiling over in 2015 and continued to worsen right up to the present”.

“Putting a SZU campus in Hong Kong may be a way of bringing mainland perspectives to Hong Kong, but not making Hong Kong students leave Hong Kong,” he told THE.

“It’s been hard to find rays of hope for Hong Kong-mainland relations developing healthily, but this may be a means to achieve some degree of understanding, cooperation and healthy competition.”

However, he warned that such a project would have to be carefully managed lest it become “a trigger point for protest”. He advised Shenzhen not to promote its programmes as a “loyalty checkoff” to the Chinese state, and to participate in local activities such as debate clubs and Model United Nations.

Professor Li called Shenzhen a “late starter” in global higher education. However, he also felt Hong Kong institutions could benefit from greater technology transfer and industry ties. “There is room for two-way cooperation,” he said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login