For most of my career, I’ve maintained at least one side gig. Recently, I have been working as a developmental editor for a global publishing company specialising in reference books.

Editing thousands of encyclopedia entries on topics ranging from fuzzy set theory to multi-species research has made me a more well-rounded scholar and a better trivia quiz competitor. Being on the other side of the desk, so to speak, has also helped me to appreciate why most people despise academics.

I’ve always enjoyed my work as an editor. I also like my editing colleagues, all intelligent, good-humoured, hard-working and considerate individuals. Unfortunately, most of my contact isn’t with them but with the contributing academics – who know me only as an editor and are often all too eager to let me know that, in their eyes, I’m much further down the food chain than they are.

Consider, for example, the following exchange. I returned an entry to an established social scientist and asked him to add first names for first references to all proper names. His reply read as follows: “You must be a complete idiot! Otherwise, you’d know that no one ever does this in a publication.” In fact, he had been given a style guide upon signing the contract.

Distasteful encounters aren’t limited to academics with seniority. Over the years, I have also had my fair share of unpleasant exchanges with graduate students and junior-level scholars – although in their case, procrastination and neglect, rather than outright arrogance, seem to be the most common problems.

Before working as an editor, I was offended by at least some of the stereotypes about academics (“those who can’t, teach”, etc). I now realise that most of them are grounded in fact. Many academics do exhibit an appalling degree of exceptionalism and entitlement. They also exhibit a surprising inability to complete even basic tasks. It is common for scholars to take weeks and even months to respond to short email queries (such as a request to verify the spelling of a proper name). When they do answer, their messages are often ridiculously inconsiderate.

On dozens of occasions, scholars have told me in earnest that they can’t attend to a few minor edits for the next three months because they are currently teaching two courses or, in the case of graduate students, taking two courses. I’m tempted to write back and let them know that if teaching or taking two courses consumes all their time, they probably need a new career! But, of course, I don’t. As an editor, it’s not my place to offer sage advice to junior colleagues.

What is most surprising is how readily academics unleash this bad behaviour on the professionals upon whom they are most dependent. After all, editors are a vital part of the academic ecosystem. This is why they are regularly invited to academic conferences: to share essential advice on how to get published.

The problem, in my view, is that there are few consequences for academics who behave badly during the editorial process. But this doesn’t mean we can’t choose to change. Here’s my advice to academic colleagues across fields who want to turn over a new leaf.

First, assume that the person editing your work is just as smart as or smarter than you. They nearly always have subject expertise on top of specialised publishing knowledge, and they generally hold at least one graduate degree. More importantly, treat them as your equals. Remember, actions speak louder than words.

Second, understand that style guides aren’t random lists of rules that editors compile to make your life miserable. They ensure consistency and are developed in consultation with subject experts. So when you disregard them, you’re riding roughshod over the collective expertise of both professional editors and your own colleagues.

Third, realise that your procrastination and neglect impacts others. When you fail to respond to emails or you submit materials or revisions months late, it has a ripple effect. You may hold back the publication of a journal or collectively authored book or create a gap in a publisher’s seasonal catalogue. Worse, since developmental editing and proofreading are often done by freelancers who may be able to invoice only for finalised work, your failure to sign off on an edit may prevent them from being paid for work they have already completed.

Fourth, start taking responsibility for the slow academic publishing process. You don’t have to look far to find articles by academics complaining about the glacial pace of academic publishing. Working as an editor, I’ve concluded that academics – both authors and peer reviewers – are largely to blame.

Finally, and most importantly, take a moment to imagine a world without publishing professionals. Who would help us produce and distribute our research – usually of no interest to a general readership and holding little market value – if all these professionals went on strike?

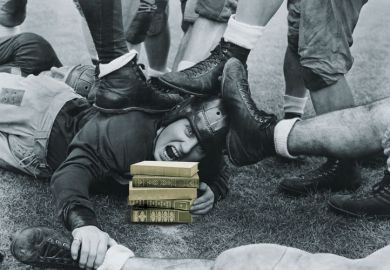

Academics who treat publishing professionals poorly are a bit like teenagers who complain to parents about their free lodgings and food: immature and appallingly ungrateful. You know what the parents say next.

Kate Eichhorn is an associate professor and chair of culture and media studies at The New School in New York City.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: My side-gigging as an editor taught me why academics are despised

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login